Bristol is the largest conurbation in South West England. The extent of its built-up area is not well-defined but its population is of the order of 500,000 - about 10% of the region’s. Bristol is not a city I enjoy going to but it is well-known for its art scene – Banksy is a Bristolian – and some current shows seemed worth a visit.

The Arnolfini arts centre moved to the run-down docks area of central Bristol 40 years ago and regards itself as having set a precedent for Tate Liverpool, the BALTIC and even the Guggenheim Bilbao as a force for regeneration. Looking at this building, just round the corner from the Arnolfini, it’s clear that there is still more to be done.

The current exhibition at the Arnolfini is Richard Long TIME AND SPACE. Long ,like Banksy, is a Bristol artist with a global reputation – for example, CAPC in Bordeaux owns nine of his works including two stone lines (Slate Line Cornwall 1981 left) – but has had shows at the Arnolfini since 1972. Long’s work can be described as conceptualist and minimalist but it also conveys the artist’s personal response to his environment. There seem to be three main areas of activity. He is probably best-known for his sculptures – assemblies of stones in the landscape or indoors, like Time and Space (2015, below) created for this exhibition:

and sculptural images like Bristol 1967/2015, recreated for it:

There are also some of his textworks:

and drawings using mud – on driftwood:

and on a larger scale directly onto the gallery walls in the form of Muddy Water Falls, 2015 made with mud from the banks of the Avon:

Long has also created Boyhood Line, 170 metres of white limestone on The Downs at Clifton in Bristol as part of the Arnolfini show.

Boyhood Line and Richard Long TIME AND SPACE continue until mid-November.

At the RWA (Royal West of England Academy) in Clifton are two exhibitions which will soon be ending. The first is Peter Randall-Page and Kate MccGwire. At first sight, one of Randall-Page’s sculptures, Wing (2009 below), has something in common with Long’s arrangements of stones, but the terra cotta tile arrangement was inspired by a microscopic study of a grasshopper wing:

The bronzes in the foreground, Inside Out (2014, above), like much of his work, are inspired by biological shapes and forms. Kate MccGwire draws from nature even more directly making complex abstract geometries with feather surfaces. Skirmish (2015, below) is made with pheasant feathers and shown in an antique dome:

while Gyre (2012, below) was made over four years with crow feathers:

Peter Randall-Page and Kate MccGwire ends on 10 September.

The other RWA show is Into the Fields: The Newlyn School and Other Artists which was at Penlee House Penzance earlier as Sons and Daughters of the Soil. I’ve posted about art in Cornwall several times and the Newlyn artists as recently as 2013. On this occasion the net has been spread wider than Penlee’s excellent collection to fetch in other painters en plein air under the influence of the Barbizon School with works like George Clausen’s In the Orchard (1871, below left) and Henry La Thangue’s Landscape Study (c1889, below right), neither set in Cornwall:

There are, as to be expected, quite a few works by Harold Harvey, for example, Blackberrying (1917, below left) and The Clay Pit (1923, below right):

And, of course, Samuel John ‘Lamorna’ Birch, for example his Morning Fills the Bowl (1926, below top) and Laura Knight’s impressive if busy Spring (1916-20, below lower):

The model in this picture is Ella Naper, better-known in the same artist’s famous Artist and Model.

Into the Fields: The Newlyn School and Other Artists ends on 6 September.

ADDENDUM 11 September

If my reservations about Bristol seem unwarranted to those who like the city, they should read Bristol, the European capital of green nannying and bureaucracy, in the Spectator on 5 September by a Bristolian, Anthony Whitehead – and the comments.

29 August 2015

27 August 2015

Some pylône posers

Most people in the UK with smartphones know all too well that, as they drive away from a built-up area, their reception moves from 3G (possibly preceded by 4G if they’re lucky) to GPRS (2G) and, if they turn off an A-road, to quite possibly nothing (0G). So it’s not surprising that the government’s 10-point plan to improve rural productivity – snappily entitled Towards a one nation economy: A 10-point plan for boosting productivity in rural areas – which came out in August has set a goal of ‘High quality, widely available mobile communications’. In particular:

- not a pretty thing, but nicely positioned between sunflowers and vines. The logos on one of the cabinets at its base reveal that it belongs to Orange, provider of communications services in France and formerly known as France Telecom:

Nearby was this notice (the name of the nearby commune has been obscured to spare the innocent any embarrassment):

It is common practice in France for public works to have an explanation of their cost and sources of funding on a placard nearby*. In this case, nearly a quarter is coming from the European Union, in particular their fund for regional development (FEDER). I would be very interested to know:

Why is the Aquitaine region, not a poor region of France and certainly not one of the EU’s neediest, receiving development funds?

On the good-luck-to-them-if-they-can-get-away-with-it principle, are UK regions receiving similar assistance? If not, why not?

Orange is a private company, albeit one with a large government shareholding, and, as in the UK, there are other mobile telephone providers – so how does that work? How are the pylônes and FEDER funds being spread across the providers or does Orange scoop the lot?

Why was a 17 weeks (semaines) of works (travaux) project, expected to end (fin) on 30 March, still not finished 17 weeks later?

More seriously, there are anecdotes that there are teams located throughout the French government dedicated to identifying and securing EU sources of funding. French civil servants probably have more experience and a better understanding of the EU budgets and their operation (often by French fonctionnaires seconded to Brussels) than those of any other country. I suspect that sadly the UK ranks with Latvia, Hungary or Malta when it comes to playing the EU system.

UDATE 28 AUGUST

This post seems to have generated more interest than many – particularly in Germany, I wonder why.

* Just an afterthought about “public works [having] an explanation of their cost and sources of funding on a placard nearby”. I would be happy to see this in the UK because it would improve the public’s understanding of how taxes are spent and the capital costs of public investment. It’s unlikely to happen for various reasons: the widespread use of PFI – government finance off balance sheet. Also in the UK not many projects are funded from multiple sources. The Treasury (UK finance ministry) would hate this – it might lose control if there were too many parties and budgets involved, particularly its ability to cancel and delay projects.

The government will put in place the right conditions, and work actively with providers, to ensure rural areas have the best possible coverage of high quality mobile services:

• The government will work closely with industry to support further improvements to mobile coverage in the UK. This will supplement the legally binding obligation on Mobile Network Operators to provide voice and SMS text coverage to 90% of the UK by 2017 and Telefonica’s licence obligation to deliver indoor 4G coverage to 98% of UK premises by 2017.

• The government proposes to extend permitted development rights to taller mobile masts in both protected and non-protected areas in England to support improved mobile connectivity, subject to conclusions from the Call for Evidence which closes on 21 August 2015. (page 13)“Taller” can be taken as meaning more than the 20 metres which is currently the maximum in the UK. 25 metre masts are in common use elsewhere in Europe, for example this mast (pylône) which is under construction in South West France:

- not a pretty thing, but nicely positioned between sunflowers and vines. The logos on one of the cabinets at its base reveal that it belongs to Orange, provider of communications services in France and formerly known as France Telecom:

Nearby was this notice (the name of the nearby commune has been obscured to spare the innocent any embarrassment):

It is common practice in France for public works to have an explanation of their cost and sources of funding on a placard nearby*. In this case, nearly a quarter is coming from the European Union, in particular their fund for regional development (FEDER). I would be very interested to know:

Why is the Aquitaine region, not a poor region of France and certainly not one of the EU’s neediest, receiving development funds?

On the good-luck-to-them-if-they-can-get-away-with-it principle, are UK regions receiving similar assistance? If not, why not?

Orange is a private company, albeit one with a large government shareholding, and, as in the UK, there are other mobile telephone providers – so how does that work? How are the pylônes and FEDER funds being spread across the providers or does Orange scoop the lot?

Why was a 17 weeks (semaines) of works (travaux) project, expected to end (fin) on 30 March, still not finished 17 weeks later?

More seriously, there are anecdotes that there are teams located throughout the French government dedicated to identifying and securing EU sources of funding. French civil servants probably have more experience and a better understanding of the EU budgets and their operation (often by French fonctionnaires seconded to Brussels) than those of any other country. I suspect that sadly the UK ranks with Latvia, Hungary or Malta when it comes to playing the EU system.

UDATE 28 AUGUST

This post seems to have generated more interest than many – particularly in Germany, I wonder why.

* Just an afterthought about “public works [having] an explanation of their cost and sources of funding on a placard nearby”. I would be happy to see this in the UK because it would improve the public’s understanding of how taxes are spent and the capital costs of public investment. It’s unlikely to happen for various reasons: the widespread use of PFI – government finance off balance sheet. Also in the UK not many projects are funded from multiple sources. The Treasury (UK finance ministry) would hate this – it might lose control if there were too many parties and budgets involved, particularly its ability to cancel and delay projects.

26 August 2015

Barbara Hepworth at Tate Britain

The British sculptor Barbara Hepworth was born in 1903 in Wakefield, West Yorkshire, where the museum named after her was opened in 2011. But from 1939 until her death in 1975, she lived and worked in South West England at St Ives in Cornwall - I posted here in 2011 about a visit to the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, part of Tate St Ives. Elsewhere in the region there are other pieces by her, for example Figure for Landscape (1960 below top) at the University of Exeter and Theme and Variations (1969–72, below lower) at what were the offices of the Cheltenham and Gloucester Building Society in Cheltenham. Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World at Tate Britain seems a welcome opportunity to take a retrospective view of her work – as such it could be regarded as complementary to that provided in 2010 for her contemporary, Henry Moore.

Although chronological, Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World is presented in an ostensibly thematic form starting with carving and moving on through studio to international modernism, equilibrium and eventually pavilion. Ann Compton, in an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Crafting Modernism Hepworth’s Practice in the 1920s, identified an important issue which the curator of a Hepworth retrospective has to face:

with several other works by Skeaping present, fails to inform the visitor (or this one, anyway) that he and Hepworth were married from 1926 until their marriage broke up in the early 1930s.

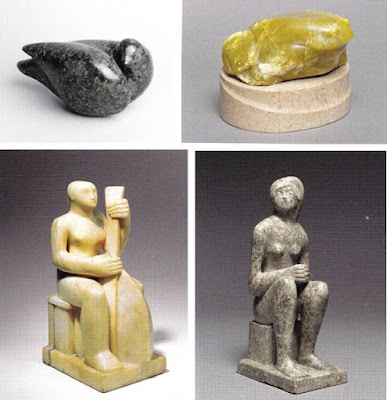

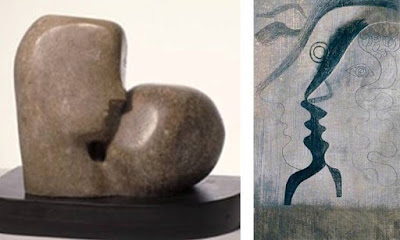

The next section, studio, has little alternative but to be realistic about Nicholson as a presence in Hepworth’s life. Anyone who left Art and Life at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2014 wondering what Ben did next will find an answer here – there are about 17 of his works alongside 24 of Hepworth’s. The couple spent most of the 1930s living and working together and studio aims, among other things, to reveal their dialogue about abstraction. There are some interesting pieces here in this regard, for example Hepworth’s Two Heads (1932, below left) and Nicholson’s painting of the couple, 1933 (St Rémy, Provence) (below right):

Perhaps not all visitors will be aware that Hepworth gave birth to their triplets in October 1934, married Nicholson in 1938 and that they would divorce in 1951.

The international modernism section is more interesting than might be expected. Not only does it show how during the 1930s her work became increasingly abstract as in Helicoids in Sphere (1938, poster above) and Three Forms (1935, below):

but also reveals her and Nicholson’s involvement with magazines (books of articles), well displayed, like Circle and Axis with contributors across Europe, some of whom would arrive in London as the political situation deteriorated. A particularly important figure was the constructivist, Naum Gabo, who after 1935 lived in Hampstead near the British modernist community and would move to Cornwall with the Nicholsons after the outbreak of war. No works by him, in particular any from 1937 onwards showing the use of strings in sculpture, are on display, although some were at Tate St Ives in 2011. Hepworth introduced strings into her work after 1938 but the earliest stringed works in this exhibition are from 1943, Sculpture and Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red (below):

although there are some drawings from 1941 in the next section, equilibrium. As far as I could tell, the exhibition does not address not only the derivation of the use of strings in Hepworth’s sculpture but also her pioneering use of holes in sculpture (Pierced Form, 1931 in pink alabaster was destroyed in the war; the exhibition catalogue (Fig 18 page 39) dates it as 1932 but Tate’s records for a later piece with the same title say 1931).

equilibrium could just as well have been called contrast – between the increasingly large abstract pieces like that above and the series of Hospital drawings she made in 1948. A donation of tropical hardwood, guarea, gives its name to the next section of four large pieces, eg Corinthos (1954-5, below):

The last section of exhibits, pavilion, consists of seven bronzes which all appeared at a retrospective at the Kroller-Muller museum in Holland in 1965, the decade in which Hepworth produced a large number of works and became firmly established as an international figure. Squares with Two Circles (1963, below) is one of the best-known.

Between equilibrium and guarea the visitor passes through the staging sculpture section, its principal feature being Dudley Shaw Ashton’s documentary made in 1952 and released in 1953, Figures in a Landscape, about Hepworth at work in St Ives (available on the BFI website). In an essay in the catalogue, Media and Movement Barbara Hepworth beyond the Lens, Inga Fraser points out that Hepworth was not happy with the film. She suggests:

The exhibition makes no mention of Hepworth’s assistants in St Ives who included Terry Frost and Terence Coventry. The catalogue is very informative, although constrained by the format and underlying philosophy of the exhibition – a timeline would have been helpful. An essay, ‘An Act of Praise’ Religion and the Work of Barbara Hepworth, by Lucy Kent reveals how taken Hepworth was with the ideas of Christian Science, a philosophy she shared with Ben Nicholson. He had been introduced to it by his first wife, Winifred.

Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World ends on 25 October 2015.

Although chronological, Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World is presented in an ostensibly thematic form starting with carving and moving on through studio to international modernism, equilibrium and eventually pavilion. Ann Compton, in an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Crafting Modernism Hepworth’s Practice in the 1920s, identified an important issue which the curator of a Hepworth retrospective has to face:

Accounts of Barbara Hepworth's career frequently divide her practice into stages defined not only by time and place but also by relationships with other key modernists, notably Henry Moore, John Skeaping and Ben Nicholson. Whilst these individuals were unquestionably important, such emphasis on personal connections is symptomatic of the containment of Hepworth's sculpture within a narrow and ultimately reflexive frame of reference. (page 13)However, it is a matter of fact that Moore and Hepworth were at the Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art together in the 1920s and neighbours in the Hampstead avant garde of the 1930s. At the time of her death Moore, five years her senior, commented “we were always like a younger sister and an older brother”. Furthermore Hepworth was married to John Skeaping and later to Ben Nicholson, having children with both. Nonetheless carving, while aiming to put Hepworth’s 1920s work in the context of other sculptors around that time practicing direct carving in wood or stone, so allowing comparison of, for example, Skeaping’s Pigeon (c1928, below top left), and her Toad (1928, below top right) and her Musician (1929-30, below lower left) and Moore’s Seated Girl (1931, below lower right):

with several other works by Skeaping present, fails to inform the visitor (or this one, anyway) that he and Hepworth were married from 1926 until their marriage broke up in the early 1930s.

The next section, studio, has little alternative but to be realistic about Nicholson as a presence in Hepworth’s life. Anyone who left Art and Life at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2014 wondering what Ben did next will find an answer here – there are about 17 of his works alongside 24 of Hepworth’s. The couple spent most of the 1930s living and working together and studio aims, among other things, to reveal their dialogue about abstraction. There are some interesting pieces here in this regard, for example Hepworth’s Two Heads (1932, below left) and Nicholson’s painting of the couple, 1933 (St Rémy, Provence) (below right):

Perhaps not all visitors will be aware that Hepworth gave birth to their triplets in October 1934, married Nicholson in 1938 and that they would divorce in 1951.

The international modernism section is more interesting than might be expected. Not only does it show how during the 1930s her work became increasingly abstract as in Helicoids in Sphere (1938, poster above) and Three Forms (1935, below):

but also reveals her and Nicholson’s involvement with magazines (books of articles), well displayed, like Circle and Axis with contributors across Europe, some of whom would arrive in London as the political situation deteriorated. A particularly important figure was the constructivist, Naum Gabo, who after 1935 lived in Hampstead near the British modernist community and would move to Cornwall with the Nicholsons after the outbreak of war. No works by him, in particular any from 1937 onwards showing the use of strings in sculpture, are on display, although some were at Tate St Ives in 2011. Hepworth introduced strings into her work after 1938 but the earliest stringed works in this exhibition are from 1943, Sculpture and Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red (below):

although there are some drawings from 1941 in the next section, equilibrium. As far as I could tell, the exhibition does not address not only the derivation of the use of strings in Hepworth’s sculpture but also her pioneering use of holes in sculpture (Pierced Form, 1931 in pink alabaster was destroyed in the war; the exhibition catalogue (Fig 18 page 39) dates it as 1932 but Tate’s records for a later piece with the same title say 1931).

equilibrium could just as well have been called contrast – between the increasingly large abstract pieces like that above and the series of Hospital drawings she made in 1948. A donation of tropical hardwood, guarea, gives its name to the next section of four large pieces, eg Corinthos (1954-5, below):

The last section of exhibits, pavilion, consists of seven bronzes which all appeared at a retrospective at the Kroller-Muller museum in Holland in 1965, the decade in which Hepworth produced a large number of works and became firmly established as an international figure. Squares with Two Circles (1963, below) is one of the best-known.

Between equilibrium and guarea the visitor passes through the staging sculpture section, its principal feature being Dudley Shaw Ashton’s documentary made in 1952 and released in 1953, Figures in a Landscape, about Hepworth at work in St Ives (available on the BFI website). In an essay in the catalogue, Media and Movement Barbara Hepworth beyond the Lens, Inga Fraser points out that Hepworth was not happy with the film. She suggests:

The portrayal of her sculpture was mediated via combination of Shaw Ashton's visual focus on the uncanny, Rainier's esoteric score, Hawkes's poetic narrative and Day-Lewis's theatrical delivery. ln light of her close involvement with the presentation of her work in other formats - exhibition, photography and in publication - it is conceivable that with these additional artistic contributions Hepworth felt her own narrative and conception of sculpture too much compromised. (page 78/79)In 1953 her son with Skeaping was killed in an air accident.

The exhibition makes no mention of Hepworth’s assistants in St Ives who included Terry Frost and Terence Coventry. The catalogue is very informative, although constrained by the format and underlying philosophy of the exhibition – a timeline would have been helpful. An essay, ‘An Act of Praise’ Religion and the Work of Barbara Hepworth, by Lucy Kent reveals how taken Hepworth was with the ideas of Christian Science, a philosophy she shared with Ben Nicholson. He had been introduced to it by his first wife, Winifred.

Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World ends on 25 October 2015.

21 August 2015

Le Corbusier in Bordeaux

2015 is the 50th anniversary of the death of the architect Le Corbusier. This post is about the houses he designed in the 1920s which are located at Pessac, a suburb of Bordeaux in South West France.

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris in 1887 in Switzerland where he trained to be an architect. In his twenties he travelled in Europe visiting Vienna and working in Paris for Auguste Perret, the pioneer of reinforced concrete, and for the industrial designer Peter Behrens in Berlin. He returned to Switzerland for most of the 1914-18 period to teach and develop theories about modern architecture for domestic dwellings. After moving to Paris in 1917 his first commission in France was the design of a water tower (below top left) at Podensac, about 30km south west of Bordeaux. Jeanneret-Gris started to use the pseudonym Le Corbusier in 1920, going into architectural practice with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, in 1922. In 1923 Le Corbusier’s influential book, Vers une architecture (below top right), was published and he designed the Villa La Roche at Auteuil (below lower), probably the first building to demonstrate his thinking about the nature of modern housing.

Impressed by the book and by Le Corbusier’s vision of low-cost housing as a means of heading off social revolution, Henri Frugès, a cultured and innovative Gironde industrialist, commissioned his practice to design a small workers’ community around a sawmill at Lège-Cap-Ferret and then a much larger garden suburb of 135 houses at Pessac. This was never completed but Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès, consisting of 51 units of seven types were constructed between 1924 and 1926 and can still be seen (less one, also the only one of its type, destroyed in 1942) in what is now called Le Cité Frugès Le Corbusier.

After a period of decline, the town of Pessac turned one of the houses into a museum (Maison Municipale, open most days) (above) in 1987 and many of the houses have been handsomely restored (below) in the original polychrome (burnt sienna, pale English green and clear oversea blue) used by Le Corbusier on exteriors only at Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès.

However, there are still some remarkable opportunities for restoration (below left and centre), and not all the inhabitants seem to have fully absorbed the modernist spirit (below right):

The “Five Points of a New Architecture” which would feature in Le Corbusier’s later work, particularly the Villa Savoye, arguably remain emergent in Pessac. The ribbon window is certainly there (below upper) but there seems to be limited use of supporting columns (below lower):

There are roof gardens:

but it seems difficult to identify much free use of the interior in the absence of supporting walls, or free design of the façades – but these are fairly small buildings as some interior views of the Maison Municipale below reveal. The extent of the wasted volume over the staircase between the first and second floors (below right) is surprising.

Even in 1924, Le Corbusier anticipated mass ownership of cars and the need for garage space on the ground floor with living spaces upstairs. The garage area of the Maison Municipale is now used to exhibit a model of the planned garden suburb:

The model plaque indicates just how advanced the scheme was in its time with central heating and showers. Unfortunately its cost probably contributed to Frugès’ bankruptcy a few years later.

Visitors to the Maison Municipale are given a booklet (in French) describing Le Cite Frugès Le Corbusier and its history (also available for download as a pdf). One example of each of the six surviving types of house has been classed as an historic monument. The types are:

Maison Gratte-ciel (“sky-scraper”) – see Maison Municipale image above

Maison Isolée (“detached” below left) and Maison Arcade (below right):

Maison Zig-Zag (below top) and Maison Quinconçe (below lower)

Maison Jumelle (“twinned”) no image available. (If there are any errors in attribution of images here, please comment!)

Should you wish to stay in a Le Corbusier house for a few days, apparently the only one available anywhere in the world is the HARG house, a Maison Gratte-ciel, in Pessac.

Le Corbusier was born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris in 1887 in Switzerland where he trained to be an architect. In his twenties he travelled in Europe visiting Vienna and working in Paris for Auguste Perret, the pioneer of reinforced concrete, and for the industrial designer Peter Behrens in Berlin. He returned to Switzerland for most of the 1914-18 period to teach and develop theories about modern architecture for domestic dwellings. After moving to Paris in 1917 his first commission in France was the design of a water tower (below top left) at Podensac, about 30km south west of Bordeaux. Jeanneret-Gris started to use the pseudonym Le Corbusier in 1920, going into architectural practice with his cousin, Pierre Jeanneret, in 1922. In 1923 Le Corbusier’s influential book, Vers une architecture (below top right), was published and he designed the Villa La Roche at Auteuil (below lower), probably the first building to demonstrate his thinking about the nature of modern housing.

Impressed by the book and by Le Corbusier’s vision of low-cost housing as a means of heading off social revolution, Henri Frugès, a cultured and innovative Gironde industrialist, commissioned his practice to design a small workers’ community around a sawmill at Lège-Cap-Ferret and then a much larger garden suburb of 135 houses at Pessac. This was never completed but Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès, consisting of 51 units of seven types were constructed between 1924 and 1926 and can still be seen (less one, also the only one of its type, destroyed in 1942) in what is now called Le Cité Frugès Le Corbusier.

After a period of decline, the town of Pessac turned one of the houses into a museum (Maison Municipale, open most days) (above) in 1987 and many of the houses have been handsomely restored (below) in the original polychrome (burnt sienna, pale English green and clear oversea blue) used by Le Corbusier on exteriors only at Les Quartiers Modernes Frugès.

However, there are still some remarkable opportunities for restoration (below left and centre), and not all the inhabitants seem to have fully absorbed the modernist spirit (below right):

The “Five Points of a New Architecture” which would feature in Le Corbusier’s later work, particularly the Villa Savoye, arguably remain emergent in Pessac. The ribbon window is certainly there (below upper) but there seems to be limited use of supporting columns (below lower):

There are roof gardens:

but it seems difficult to identify much free use of the interior in the absence of supporting walls, or free design of the façades – but these are fairly small buildings as some interior views of the Maison Municipale below reveal. The extent of the wasted volume over the staircase between the first and second floors (below right) is surprising.

Even in 1924, Le Corbusier anticipated mass ownership of cars and the need for garage space on the ground floor with living spaces upstairs. The garage area of the Maison Municipale is now used to exhibit a model of the planned garden suburb:

The model plaque indicates just how advanced the scheme was in its time with central heating and showers. Unfortunately its cost probably contributed to Frugès’ bankruptcy a few years later.

Visitors to the Maison Municipale are given a booklet (in French) describing Le Cite Frugès Le Corbusier and its history (also available for download as a pdf). One example of each of the six surviving types of house has been classed as an historic monument. The types are:

Maison Gratte-ciel (“sky-scraper”) – see Maison Municipale image above

Maison Isolée (“detached” below left) and Maison Arcade (below right):

Maison Zig-Zag (below top) and Maison Quinconçe (below lower)

Maison Jumelle (“twinned”) no image available. (If there are any errors in attribution of images here, please comment!)

Should you wish to stay in a Le Corbusier house for a few days, apparently the only one available anywhere in the world is the HARG house, a Maison Gratte-ciel, in Pessac.

17 August 2015

Noah Baumbach’s ‘Mistress America’

Only four months ago I posted about Noah Baumbach’s comedy While We Were Young and now his Mistress America has just been released in the UK. Although both films are set in current-day New York and both share a theme of the implications for friendships of differences in age, in fact Mistress America has more in common with Baumbach’s 2012 Frances Ha. For a start both those films were co-written by Baumbach with Greta Gerwig who also takes the eponymous leading parts.

The plot of Mistress America spans the eight weeks or so between the start of the university year and Thanksgiving. Tracy (Lola Kirke) has just started her degree in English Literature and is finding it hard to make her mark on campus socially or with the elite Mobius Society of would-be literati. Her mother is remarrying and encourages Tracy to get in touch with her soon-to-be older stepsister, Brooke (Gerwig). Brooke is 30, Tracy 18, ages at which the difference between them ("contemporaries" blags Brooke at one point) is more significant than it would be at 54 and 42, say. At first Tracy is dazzled by Brooke’s knowledge of the ropes and tropes of the youthful Manhattan lifestyle but she soon realises that Brooke is all hat and no cattle. Tracy’s depiction of a thinly-disguised Brooke in a short story gives the film its name and gains Tracy entry to Mobius.

Brooke’s fanciful plans to open a restaurant hit a financial crisis and she decides to seek funds from a wealthy former boy-friend Dylan (Michael Chernus), now married to a former rival of Brooke’s, Mamie-Claire (Heather Lind), and living in a splendidly positioned Modernist house in Connecticut. Tracy and a couple of her fellow students in tow, Brooke doorsteps Dylan and with the support of Dylan's paediatrician neighbour and a pregnant friend of Mamie-Claire, a seven-person ensemble piece ensues. Eventually Brooke is extricated from her money problems and decides to leave town.

Frances Ha appears in Wikipedia’s list of Mumblecore movies, “characterized by low budget production values and amateur actors, heavily focused on naturalistic dialogue”. I have to confess that the early parts of Mistress America, set in a student milieu and with young actors speaking contemporary American, were not easy for my ageing English ears to follow. Interestingly the Connecticut sequence with older actors presented no such problem. There is some very witty dialogue throughout and Gerwig, only 32, has a great comic talent as performer and presumably as a writer. She sees the professional side of her relationship with Baumbach as having parallels with the great song-writing partnerships and she may well be right. Hopefully there is much more to come from them.

I think the critics’ ratings of 4* and 5* for Mistress America are a little generous, perhaps there isn’t much else around in August, although I sometimes wonder whether I’ve seen the same film. In the Financial Times, Nigel Andrews gushed:

By the way, at one point on her own in Brooke’s squat, Tracy settles down with a drink from a bottle whose label ends “…ET”. Lillet Blanc is an aperitif produced in the Gironde in South West France, not well-known in the UK but popular for a long time in New York and other sophisticated parts of the US as a cocktail ingredient. Supposedly the American taste for it was acquired on the transatlantic liners. Personally I find Lillet too sweet, even when served well-chilled as recommended. Unlike Mistress America in which Baumbach and Gerwig have the balance between the comic and the acerbic about right.

UPDATE 2 September

Richard Brody, The New Yorker's veteran film critic, whose views are far more worth reading than mine, has a very high opinion of Mistress America:

The plot of Mistress America spans the eight weeks or so between the start of the university year and Thanksgiving. Tracy (Lola Kirke) has just started her degree in English Literature and is finding it hard to make her mark on campus socially or with the elite Mobius Society of would-be literati. Her mother is remarrying and encourages Tracy to get in touch with her soon-to-be older stepsister, Brooke (Gerwig). Brooke is 30, Tracy 18, ages at which the difference between them ("contemporaries" blags Brooke at one point) is more significant than it would be at 54 and 42, say. At first Tracy is dazzled by Brooke’s knowledge of the ropes and tropes of the youthful Manhattan lifestyle but she soon realises that Brooke is all hat and no cattle. Tracy’s depiction of a thinly-disguised Brooke in a short story gives the film its name and gains Tracy entry to Mobius.

Brooke’s fanciful plans to open a restaurant hit a financial crisis and she decides to seek funds from a wealthy former boy-friend Dylan (Michael Chernus), now married to a former rival of Brooke’s, Mamie-Claire (Heather Lind), and living in a splendidly positioned Modernist house in Connecticut. Tracy and a couple of her fellow students in tow, Brooke doorsteps Dylan and with the support of Dylan's paediatrician neighbour and a pregnant friend of Mamie-Claire, a seven-person ensemble piece ensues. Eventually Brooke is extricated from her money problems and decides to leave town.

Frances Ha appears in Wikipedia’s list of Mumblecore movies, “characterized by low budget production values and amateur actors, heavily focused on naturalistic dialogue”. I have to confess that the early parts of Mistress America, set in a student milieu and with young actors speaking contemporary American, were not easy for my ageing English ears to follow. Interestingly the Connecticut sequence with older actors presented no such problem. There is some very witty dialogue throughout and Gerwig, only 32, has a great comic talent as performer and presumably as a writer. She sees the professional side of her relationship with Baumbach as having parallels with the great song-writing partnerships and she may well be right. Hopefully there is much more to come from them.

I think the critics’ ratings of 4* and 5* for Mistress America are a little generous, perhaps there isn’t much else around in August, although I sometimes wonder whether I’ve seen the same film. In the Financial Times, Nigel Andrews gushed:

It stars a Greta Gerwig more than ever resembling cinema’s earlier Greta G, her tomboy-Garbo features ideal for the title-nicknamed heroine.Gerwig has many strengths, but being Garboesque is surely not one of them. Andrews then tells his readers that:

During a house-party weekend, half a dozen Brooke-related characters, indentured to her worship, form tableau vivant tribunals to critique Tracy’s acidic, Brooke-based short story, titled Mistress America.It wasn’t a house-party weekend, two of the three other women present didn’t like Brooke at all and nobody moves or speaks in a tableau vivant. (I guess Andrews is busy brushing up his Kurosawa).

By the way, at one point on her own in Brooke’s squat, Tracy settles down with a drink from a bottle whose label ends “…ET”. Lillet Blanc is an aperitif produced in the Gironde in South West France, not well-known in the UK but popular for a long time in New York and other sophisticated parts of the US as a cocktail ingredient. Supposedly the American taste for it was acquired on the transatlantic liners. Personally I find Lillet too sweet, even when served well-chilled as recommended. Unlike Mistress America in which Baumbach and Gerwig have the balance between the comic and the acerbic about right.

UPDATE 2 September

Richard Brody, The New Yorker's veteran film critic, whose views are far more worth reading than mine, has a very high opinion of Mistress America:

... “Mistress America” is a masterwork of literary cinema in the other, qualitative sense: it isn’t merely about literature; it’s a work of brilliant writing, one of the most exquisite of recent screenplays.

10 August 2015

The Frankton Memorial, Le Verdon-sur-Mer

There has been a revival of interest in the December 1942 Operation Frankton in the last few years. Better-known in the past as the Cockleshell Heroes operation, it was a clandestine attack on German shipping in Bordeaux harbour mounted by twelve Royal Marines commandos under Major HG "Blondie" Hasler. Infiltrated by submarine to the mouth of the Gironde estuary, the plan was to navigate their way by two-man canoes (“cockleshells”) up the heavily defended estuary for 70 miles to the harbour.

Five canoes set off with ten men: two died of hypothermia, six were captured and executed by the Germans, two survived including Hasler. Six ships were damaged, one extensively. Far from being futile, Frankton demonstrated the need for inter-agency cooperation while planning for the invasion of France in 1944.

In 2012 Paddy Ashdown’s A Brilliant Little Operation: The Cockleshell Heroes and the Most Courageous Raid of World War 2 was published, a BBC2 Timewatch documentary, The Most Courageous Raid of WWII, narrated by Ashdown, being shown the previous year. Ashdown’s account offers perspectives from someone who is both a senior politician and a former Royal Marines officer who had met Hasler. The documentary and book reveal that unknown to the Combined Operations Command who controlled the Marines, the Special Operations Executive were running similar operations at the same time. Inter-agency issues are explored further in Tom Keene’s Cloak of Enemies: Churchill's SOE, Enemies at Home and the Cockleshell Heroes, also published in 2012. Prior to these two books, the best-known account of the operation had been C. E. Lucas Phillips’ Cockleshell Heroes published in 1956.

In 2011 a memorial commemorating Frankton was installed on the southern edge of the mouth of the estuary at the Pointe de Grave in the commune of Le Verdon-sur-Mer (33). As it is fairly remote, two hours’ drive from Bordeaux, the photographs below may be of interest to anyone unable to visit the site. The memorial was designed by Baca Architects and constructed by Albion Stone Restoration for the Royal Marines Association. Both companies’ websites are worth consulting, Baca explaining that:

and offer descriptions:

Stone 1: Crests of the participants in Operation Frankton: The Royal Navy, Combined Operations Command, The Royal Marines, The French Resistance

Stone 2: This carries the text tributes in English and French to the gallant 10 Royal Marines, and each named beneath a carved floral motif of the Rose, the Thistle and the Shamrock, representing the birth places of the men England, Scotland and Ireland. There follows tributes to the Capt and crew of HMS Tuna and to the courage of local French people who helped the marines, three, named on this plaque who were deported to concentration camp in Germany, and did not return arrested for being associated with Op Frankton, coincidentally, except for one Lucien Gody who raced late at night to warn Hasler and Sparks to flee their hiding place as Germans were close by. At the base are the words of Lord Mountbatten about the 10 men.

Stone 3: There is a depiction of the Submarine HMS Tuna, together with the five canoes just after the launch, where they were to be together for the very last time. Two crews were lost in two vicious Tide-races on the first night, two men died of hypothermia and two were captured when they arrived exhausted on the beach and were executed four days later. [The quotation is from the C. E. Lucas Phillips’ book, mentioned above.]

Stone 4: This carries the narrative account of Operation Frankton, again all repeated in French.

The memorial is constructed in Grove Whitbed stone which has a surface markedly different from the limestone widely used for buildings in the Gironde.

The Pointe de Grave is exposed to salt water spray from the Bay of Biscay and the effects of corrosion are already beginning to show on the Frankton memorial. Nearby is another memorial which commemorates the American Expeditionary Forces under General Pershing which arrived in France in 1917. Hopefully it will receive some restoration before the centenary in 2017.

|

| From www.c-royan.com |

In 2012 Paddy Ashdown’s A Brilliant Little Operation: The Cockleshell Heroes and the Most Courageous Raid of World War 2 was published, a BBC2 Timewatch documentary, The Most Courageous Raid of WWII, narrated by Ashdown, being shown the previous year. Ashdown’s account offers perspectives from someone who is both a senior politician and a former Royal Marines officer who had met Hasler. The documentary and book reveal that unknown to the Combined Operations Command who controlled the Marines, the Special Operations Executive were running similar operations at the same time. Inter-agency issues are explored further in Tom Keene’s Cloak of Enemies: Churchill's SOE, Enemies at Home and the Cockleshell Heroes, also published in 2012. Prior to these two books, the best-known account of the operation had been C. E. Lucas Phillips’ Cockleshell Heroes published in 1956.

In 2011 a memorial commemorating Frankton was installed on the southern edge of the mouth of the estuary at the Pointe de Grave in the commune of Le Verdon-sur-Mer (33). As it is fairly remote, two hours’ drive from Bordeaux, the photographs below may be of interest to anyone unable to visit the site. The memorial was designed by Baca Architects and constructed by Albion Stone Restoration for the Royal Marines Association. Both companies’ websites are worth consulting, Baca explaining that:

The Memorial remembers the 10 courageous Royal Marines, the bravery of the captain and crew of the submarine HMS Tuna and the courageous French citizens who assisted the Royal Marines. The four substantial Portland stone blocks step up towards the front of the memorial, where one may envisage a symbolic representation of the Royal Marines emerging from the sea, standing proud. As one moves around the memorial, different compositions are revealed. The separate stones create individual settings for insignia, as well as stones at the flanks to show the story of mission.Albion explain that:

The staggered blocks create a dynamic ensemble, growing bolder to the front. The blocks are adorned with polished plaques that commemorative the heroism and retell the story. Symbolically the four stones represent four figures emerging from the sea.

and offer descriptions:

Stone 1: Crests of the participants in Operation Frankton: The Royal Navy, Combined Operations Command, The Royal Marines, The French Resistance

Stone 2: This carries the text tributes in English and French to the gallant 10 Royal Marines, and each named beneath a carved floral motif of the Rose, the Thistle and the Shamrock, representing the birth places of the men England, Scotland and Ireland. There follows tributes to the Capt and crew of HMS Tuna and to the courage of local French people who helped the marines, three, named on this plaque who were deported to concentration camp in Germany, and did not return arrested for being associated with Op Frankton, coincidentally, except for one Lucien Gody who raced late at night to warn Hasler and Sparks to flee their hiding place as Germans were close by. At the base are the words of Lord Mountbatten about the 10 men.

Stone 3: There is a depiction of the Submarine HMS Tuna, together with the five canoes just after the launch, where they were to be together for the very last time. Two crews were lost in two vicious Tide-races on the first night, two men died of hypothermia and two were captured when they arrived exhausted on the beach and were executed four days later. [The quotation is from the C. E. Lucas Phillips’ book, mentioned above.]

Stone 4: This carries the narrative account of Operation Frankton, again all repeated in French.

The memorial is constructed in Grove Whitbed stone which has a surface markedly different from the limestone widely used for buildings in the Gironde.

The Pointe de Grave is exposed to salt water spray from the Bay of Biscay and the effects of corrosion are already beginning to show on the Frankton memorial. Nearby is another memorial which commemorates the American Expeditionary Forces under General Pershing which arrived in France in 1917. Hopefully it will receive some restoration before the centenary in 2017.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)