Bristol is the largest conurbation in South West England. The extent of its built-up area is not well-defined but its population is of the order of 500,000 - about 10% of the region’s. Bristol is not a city I enjoy going to but it is well-known for its art scene – Banksy is a Bristolian – and some current shows seemed worth a visit.

The Arnolfini arts centre moved to the run-down docks area of central Bristol 40 years ago and regards itself as having set a precedent for Tate Liverpool, the BALTIC and even the Guggenheim Bilbao as a force for regeneration. Looking at this building, just round the corner from the Arnolfini, it’s clear that there is still more to be done.

The current exhibition at the Arnolfini is Richard Long TIME AND SPACE. Long ,like Banksy, is a Bristol artist with a global reputation – for example, CAPC in Bordeaux owns nine of his works including two stone lines (Slate Line Cornwall 1981 left) – but has had shows at the Arnolfini since 1972. Long’s work can be described as conceptualist and minimalist but it also conveys the artist’s personal response to his environment. There seem to be three main areas of activity. He is probably best-known for his sculptures – assemblies of stones in the landscape or indoors, like Time and Space (2015, below) created for this exhibition:

and sculptural images like Bristol 1967/2015, recreated for it:

There are also some of his textworks:

and drawings using mud – on driftwood:

and on a larger scale directly onto the gallery walls in the form of Muddy Water Falls, 2015 made with mud from the banks of the Avon:

Long has also created Boyhood Line, 170 metres of white limestone on The Downs at Clifton in Bristol as part of the Arnolfini show.

Boyhood Line and Richard Long TIME AND SPACE continue until mid-November.

At the RWA (Royal West of England Academy) in Clifton are two exhibitions which will soon be ending. The first is Peter Randall-Page and Kate MccGwire. At first sight, one of Randall-Page’s sculptures, Wing (2009 below), has something in common with Long’s arrangements of stones, but the terra cotta tile arrangement was inspired by a microscopic study of a grasshopper wing:

The bronzes in the foreground, Inside Out (2014, above), like much of his work, are inspired by biological shapes and forms. Kate MccGwire draws from nature even more directly making complex abstract geometries with feather surfaces. Skirmish (2015, below) is made with pheasant feathers and shown in an antique dome:

while Gyre (2012, below) was made over four years with crow feathers:

Peter Randall-Page and Kate MccGwire ends on 10 September.

The other RWA show is Into the Fields: The Newlyn School and Other Artists which was at Penlee House Penzance earlier as Sons and Daughters of the Soil. I’ve posted about art in Cornwall several times and the Newlyn artists as recently as 2013. On this occasion the net has been spread wider than Penlee’s excellent collection to fetch in other painters en plein air under the influence of the Barbizon School with works like George Clausen’s In the Orchard (1871, below left) and Henry La Thangue’s Landscape Study (c1889, below right), neither set in Cornwall:

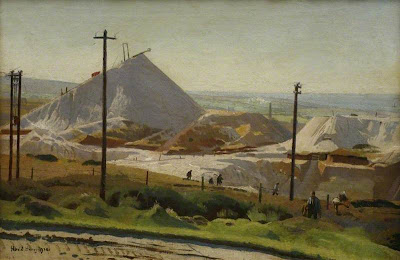

There are, as to be expected, quite a few works by Harold Harvey, for example, Blackberrying (1917, below left) and The Clay Pit (1923, below right):

And, of course, Samuel John ‘Lamorna’ Birch, for example his Morning Fills the Bowl (1926, below top) and Laura Knight’s impressive if busy Spring (1916-20, below lower):

The model in this picture is Ella Naper, better-known in the same artist’s famous Artist and Model.

Into the Fields: The Newlyn School and Other Artists ends on 6 September.

ADDENDUM 11 September

If my reservations about Bristol seem unwarranted to those who like the city, they should read Bristol, the European capital of green nannying and bureaucracy, in the Spectator on 5 September by a Bristolian, Anthony Whitehead – and the comments.

Showing posts with label Penlee House. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Penlee House. Show all posts

29 August 2015

15 June 2013

Christopher Menaul’s ‘Summer in February’

Christopher Menaul has been directing drama series and films for TV for over 40 years but Summer in February seems to be his first film for commercial release. I mentioned it last November in a post about the Laura Knight exhibition in Worcester. The film, “based on a true story”, is set in Cornwall (SW England) in 1913 and was scripted by Jonathan Smith from his novel of the same title about a love triangle among the bohemian community of artists working at that time in Lamorna. In the film Laura (Hattie Morahan) and her husband Harold (Shaun Dingwall) are onlookers as the young emerging artistic talent of the day, AJ Munnings (Dominic Cooper), and the much more conventional local land agent and army officer, Gilbert Evans (Dan Stevens), vie for the affections of Florence Carter-Wood (Emily Browning).

Summer in February is handsomely filmed against some of the finest coastal scenery in Europe and the period settings are as picturesque as some of the works in the Artists in Cornwall show earlier this year, or those to be found at the Penlee House Gallery in Penzance. However, I wasn’t totally persuaded by its characters’ behaviour, although well-acted.Would Laura and Harold have skinny-dipped in quite so unembarrassed a fashion in front of Gilbert and Florence? [See comments below] Would AJ have used f-words in front of women in 1913, Menaul and Cooper seemingly having decided to portray him as a YBA du temps? Did Munnings, notorious for his speech against modernism in 1949, have such a down on Picasso as early as 1913 – the latter’s style in AJ’s parody seems to belong to a later period? A useful, if not impartial, source of information about Munnings is provided by the Castle House Trust’s website. Although there is no mention of his first wife, their biography does point out that “he spent the first three years of the 1914-18 war mainly in Lamorna” and that “It was from Lamorna that he made his excursions to Hampshire where he had discovered, in the gypsy hop pickers, a wealth of painting material.”

Dr James Fox, in his recently repeated BBC4 series, British Masters, put Munnings into context and drew attention to his considerable skill as an artist. Actors aren’t expected to possess such skills of course, but have to look convincing when they take the part of artists (or, worse, musicians), as does the art they are working on (The Morning Ride, sold at Christie’s in 2000, right). The Spectator sent their art critic, Andrew Lambirth, to review Summer in February and he thought the problem had been handled well.

By an odd coincidence, there have been two period films released in the last two weeks, one set in SW France and the other in SW England, both dealing with the consequences for women of choosing the wrong husband!

Summer in February is handsomely filmed against some of the finest coastal scenery in Europe and the period settings are as picturesque as some of the works in the Artists in Cornwall show earlier this year, or those to be found at the Penlee House Gallery in Penzance. However, I wasn’t totally persuaded by its characters’ behaviour, although well-acted.

Dr James Fox, in his recently repeated BBC4 series, British Masters, put Munnings into context and drew attention to his considerable skill as an artist. Actors aren’t expected to possess such skills of course, but have to look convincing when they take the part of artists (or, worse, musicians), as does the art they are working on (The Morning Ride, sold at Christie’s in 2000, right). The Spectator sent their art critic, Andrew Lambirth, to review Summer in February and he thought the problem had been handled well.

By an odd coincidence, there have been two period films released in the last two weeks, one set in SW France and the other in SW England, both dealing with the consequences for women of choosing the wrong husband!

9 March 2013

Artists in Cornwall at Two Temple Place London

Previous posts here have touched on the artists working in and around Newlyn, Cornwall (SW England) at the end of the 19th century and on Stanhope Forbes’ en plein air realist masterpiece, Fish Sale on a Cornish Beach 1885 (detail in the poster above) which was lent last year to Compton Verney. This work and many others by artists based in West Cornwall from the 1880s to the 1920s feature in Two Temple Place’s exhibition Amongst Heroes: the Artist in Working Cornwall.

The Bulldog Trust’s intention is to bring publicly-owned art from around the UK to Two Temple Place, the opulent late-Victorian mansion built by William Waldorf Astor on London’s Embankment. This show draws on key works from the Royal Cornwall Museum and Penlee House Gallery and Museum and other public and private collections in Conrwall and elsewhere.

The successive galleries present a fine selection of paintings, many of them unfamiliar, and some other items dealing with various aspects of the work of the ordinary Cornish people of the period: fishing (Charles Napier Henry Pilchards 1897, above) crafts, agriculture and mining (Harold Harvey A China Clay Pit, Lewidden c1922, below), as well as individual portraits (Henry Scott Tuke Portrait of Jack Rowling 1888, right).

The exhibition is a delight if you are at all interested in art of this kind. Furthermore, admission is free and the catalogue a very reasonable price (though the quality of its reproductions is a little disappointing). ‘Anticipointment’ rating: a rare 1 out of 5, the lower being the better.

Amongst Heroes: the Artist in Working Cornwall continues until 14 April.

Quite different, but only a short walk away, is the Courtauld Gallery's Becoming Picasso: Paris 1901.

12 June 2011

Tate and Hepworth at St Ives

A post last month described the recent exhibition at Compton Verney of works by Alfred Wallis and Ben Nicholson, two artists associated with St Ives (Cornwall, SW England). Virginia Button’s St Ives Artists: A Companion, published by the Tate, provides a helpful introduction to 18 of the best-known members of the colony of artists working there in a significant way from the 1930s to the 1960s (and also to the potter Bernard Leach.

The mission of the Tate’s outpost at St Ives is to present 20th-century art in the context of Cornwall. The displays change regularly, allowing a different selection from the Tate's extensive collection of St Ives art to be shown each year. Visitors need to be aware that there is no permanent display of St Ives artists’ work in the Gallery. However, this year the Tate St Ives Summer Exhibition includes works by two artists with local links: Naum Gabo and Margaret Mellis, both active there during the Second World War.

The St Ives artist whose works are permanently held locally is Barbara Hepworth. Her former studio, now Museum and Sculpture Garden, is near, and part of, Tate St Ives. Gabo and his wife, and Hepworth and her husband, Ben Nicholson (and their triplets), moved to Cornwall in 1939, having been part of the Hampstead community of artists and sculptors from earlier in the 1930s. Common influences such as the use of strings in sculpture can be seen in the Gabo and Hepworth pieces currently at St Ives. Mellis and her first husband also moved to St Ives in 1939 (the Nicholsons lived with them for a while). The work of Nicholson and Gabo led Mellis to experiment with collages, some of which are exhibited. Most of her work on display is from the 1970s: attractive constructions made from driftwood found on the beach at Southwold (Suffolk), where she lived until her death in 2009 at the age of 95.

The St Ives artist whose works are permanently held locally is Barbara Hepworth. Her former studio, now Museum and Sculpture Garden, is near, and part of, Tate St Ives. Gabo and his wife, and Hepworth and her husband, Ben Nicholson (and their triplets), moved to Cornwall in 1939, having been part of the Hampstead community of artists and sculptors from earlier in the 1930s. Common influences such as the use of strings in sculpture can be seen in the Gabo and Hepworth pieces currently at St Ives. Mellis and her first husband also moved to St Ives in 1939 (the Nicholsons lived with them for a while). The work of Nicholson and Gabo led Mellis to experiment with collages, some of which are exhibited. Most of her work on display is from the 1970s: attractive constructions made from driftwood found on the beach at Southwold (Suffolk), where she lived until her death in 2009 at the age of 95.

The St Ives colony was the second such in west Cornwall. There had been rail links to Penzance from 1859 and through services on the Great Western Railway reached St Ives in 1877. The area soon attracted artistic attention: the scenery, the fisherfolk and their boats, together with the exceptional quality of the light and the vogue for painting en plein air, influenced by the naturalism of French painters of the time, led to a settlement of artists at Newlyn. Part of the attraction of Newlyn was its similarity to Brittany. Penlee House Museum and Gallery in Penzance is the only Cornish public gallery specialising in the Newlyn School artists including Stanhope and Elizabeth Forbes, Walter Langley, Harold Harvey and Laura Knight.

As well as a selection from its permanent collection, Penlee House is running an exhibition this summer, Walter Langley and the Birmingham Boys, featuring some of the artists who came from the Midlands to work in Newlyn from the 1880s onwards.

There are tickets available for combined entry to Tate St Ives, including the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, and Penlee House, which offer a useful saving – these do not seem to be publicised on either organisations’ websites, but are featured at the Tate St Ives ticket desk.

Among the London galleries, Messum’s has a continuing interest in West Country paintings from the 1880s onwards. Locally, the Market House Gallery in Marazion holds a good stock of prints by Terry Frost and others, any of which might suit the whitewashed walls of what was once a fisherman’s cottage.

However, any visitor with a taste for late St Ives abstractionism, should not ignore the vagaries of the Cornish weather, well-appreciated by the realists of the Newlyn School:

The mission of the Tate’s outpost at St Ives is to present 20th-century art in the context of Cornwall. The displays change regularly, allowing a different selection from the Tate's extensive collection of St Ives art to be shown each year. Visitors need to be aware that there is no permanent display of St Ives artists’ work in the Gallery. However, this year the Tate St Ives Summer Exhibition includes works by two artists with local links: Naum Gabo and Margaret Mellis, both active there during the Second World War.

The St Ives artist whose works are permanently held locally is Barbara Hepworth. Her former studio, now Museum and Sculpture Garden, is near, and part of, Tate St Ives. Gabo and his wife, and Hepworth and her husband, Ben Nicholson (and their triplets), moved to Cornwall in 1939, having been part of the Hampstead community of artists and sculptors from earlier in the 1930s. Common influences such as the use of strings in sculpture can be seen in the Gabo and Hepworth pieces currently at St Ives. Mellis and her first husband also moved to St Ives in 1939 (the Nicholsons lived with them for a while). The work of Nicholson and Gabo led Mellis to experiment with collages, some of which are exhibited. Most of her work on display is from the 1970s: attractive constructions made from driftwood found on the beach at Southwold (Suffolk), where she lived until her death in 2009 at the age of 95.

The St Ives artist whose works are permanently held locally is Barbara Hepworth. Her former studio, now Museum and Sculpture Garden, is near, and part of, Tate St Ives. Gabo and his wife, and Hepworth and her husband, Ben Nicholson (and their triplets), moved to Cornwall in 1939, having been part of the Hampstead community of artists and sculptors from earlier in the 1930s. Common influences such as the use of strings in sculpture can be seen in the Gabo and Hepworth pieces currently at St Ives. Mellis and her first husband also moved to St Ives in 1939 (the Nicholsons lived with them for a while). The work of Nicholson and Gabo led Mellis to experiment with collages, some of which are exhibited. Most of her work on display is from the 1970s: attractive constructions made from driftwood found on the beach at Southwold (Suffolk), where she lived until her death in 2009 at the age of 95.The St Ives colony was the second such in west Cornwall. There had been rail links to Penzance from 1859 and through services on the Great Western Railway reached St Ives in 1877. The area soon attracted artistic attention: the scenery, the fisherfolk and their boats, together with the exceptional quality of the light and the vogue for painting en plein air, influenced by the naturalism of French painters of the time, led to a settlement of artists at Newlyn. Part of the attraction of Newlyn was its similarity to Brittany. Penlee House Museum and Gallery in Penzance is the only Cornish public gallery specialising in the Newlyn School artists including Stanhope and Elizabeth Forbes, Walter Langley, Harold Harvey and Laura Knight.

As well as a selection from its permanent collection, Penlee House is running an exhibition this summer, Walter Langley and the Birmingham Boys, featuring some of the artists who came from the Midlands to work in Newlyn from the 1880s onwards.

There are tickets available for combined entry to Tate St Ives, including the Barbara Hepworth Museum and Sculpture Garden, and Penlee House, which offer a useful saving – these do not seem to be publicised on either organisations’ websites, but are featured at the Tate St Ives ticket desk.

Among the London galleries, Messum’s has a continuing interest in West Country paintings from the 1880s onwards. Locally, the Market House Gallery in Marazion holds a good stock of prints by Terry Frost and others, any of which might suit the whitewashed walls of what was once a fisherman’s cottage.

However, any visitor with a taste for late St Ives abstractionism, should not ignore the vagaries of the Cornish weather, well-appreciated by the realists of the Newlyn School:

|

| The Rain it Raineth Every Day by Norman Garstin |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)