Although chronological, Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World is presented in an ostensibly thematic form starting with carving and moving on through studio to international modernism, equilibrium and eventually pavilion. Ann Compton, in an essay in the exhibition catalogue, Crafting Modernism Hepworth’s Practice in the 1920s, identified an important issue which the curator of a Hepworth retrospective has to face:

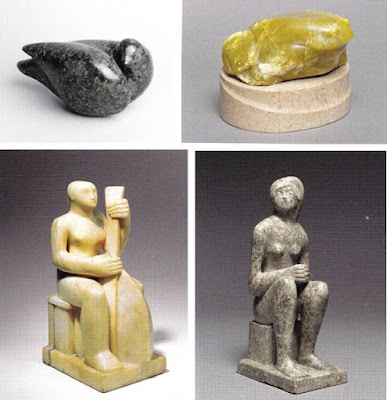

Accounts of Barbara Hepworth's career frequently divide her practice into stages defined not only by time and place but also by relationships with other key modernists, notably Henry Moore, John Skeaping and Ben Nicholson. Whilst these individuals were unquestionably important, such emphasis on personal connections is symptomatic of the containment of Hepworth's sculpture within a narrow and ultimately reflexive frame of reference. (page 13)However, it is a matter of fact that Moore and Hepworth were at the Leeds School of Art and the Royal College of Art together in the 1920s and neighbours in the Hampstead avant garde of the 1930s. At the time of her death Moore, five years her senior, commented “we were always like a younger sister and an older brother”. Furthermore Hepworth was married to John Skeaping and later to Ben Nicholson, having children with both. Nonetheless carving, while aiming to put Hepworth’s 1920s work in the context of other sculptors around that time practicing direct carving in wood or stone, so allowing comparison of, for example, Skeaping’s Pigeon (c1928, below top left), and her Toad (1928, below top right) and her Musician (1929-30, below lower left) and Moore’s Seated Girl (1931, below lower right):

with several other works by Skeaping present, fails to inform the visitor (or this one, anyway) that he and Hepworth were married from 1926 until their marriage broke up in the early 1930s.

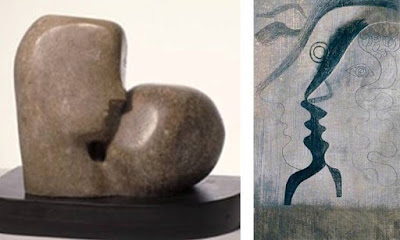

The next section, studio, has little alternative but to be realistic about Nicholson as a presence in Hepworth’s life. Anyone who left Art and Life at the Dulwich Picture Gallery in 2014 wondering what Ben did next will find an answer here – there are about 17 of his works alongside 24 of Hepworth’s. The couple spent most of the 1930s living and working together and studio aims, among other things, to reveal their dialogue about abstraction. There are some interesting pieces here in this regard, for example Hepworth’s Two Heads (1932, below left) and Nicholson’s painting of the couple, 1933 (St Rémy, Provence) (below right):

Perhaps not all visitors will be aware that Hepworth gave birth to their triplets in October 1934, married Nicholson in 1938 and that they would divorce in 1951.

The international modernism section is more interesting than might be expected. Not only does it show how during the 1930s her work became increasingly abstract as in Helicoids in Sphere (1938, poster above) and Three Forms (1935, below):

but also reveals her and Nicholson’s involvement with magazines (books of articles), well displayed, like Circle and Axis with contributors across Europe, some of whom would arrive in London as the political situation deteriorated. A particularly important figure was the constructivist, Naum Gabo, who after 1935 lived in Hampstead near the British modernist community and would move to Cornwall with the Nicholsons after the outbreak of war. No works by him, in particular any from 1937 onwards showing the use of strings in sculpture, are on display, although some were at Tate St Ives in 2011. Hepworth introduced strings into her work after 1938 but the earliest stringed works in this exhibition are from 1943, Sculpture and Colour (Oval Form) Pale Blue and Red (below):

although there are some drawings from 1941 in the next section, equilibrium. As far as I could tell, the exhibition does not address not only the derivation of the use of strings in Hepworth’s sculpture but also her pioneering use of holes in sculpture (Pierced Form, 1931 in pink alabaster was destroyed in the war; the exhibition catalogue (Fig 18 page 39) dates it as 1932 but Tate’s records for a later piece with the same title say 1931).

equilibrium could just as well have been called contrast – between the increasingly large abstract pieces like that above and the series of Hospital drawings she made in 1948. A donation of tropical hardwood, guarea, gives its name to the next section of four large pieces, eg Corinthos (1954-5, below):

The last section of exhibits, pavilion, consists of seven bronzes which all appeared at a retrospective at the Kroller-Muller museum in Holland in 1965, the decade in which Hepworth produced a large number of works and became firmly established as an international figure. Squares with Two Circles (1963, below) is one of the best-known.

Between equilibrium and guarea the visitor passes through the staging sculpture section, its principal feature being Dudley Shaw Ashton’s documentary made in 1952 and released in 1953, Figures in a Landscape, about Hepworth at work in St Ives (available on the BFI website). In an essay in the catalogue, Media and Movement Barbara Hepworth beyond the Lens, Inga Fraser points out that Hepworth was not happy with the film. She suggests:

The portrayal of her sculpture was mediated via combination of Shaw Ashton's visual focus on the uncanny, Rainier's esoteric score, Hawkes's poetic narrative and Day-Lewis's theatrical delivery. ln light of her close involvement with the presentation of her work in other formats - exhibition, photography and in publication - it is conceivable that with these additional artistic contributions Hepworth felt her own narrative and conception of sculpture too much compromised. (page 78/79)In 1953 her son with Skeaping was killed in an air accident.

The exhibition makes no mention of Hepworth’s assistants in St Ives who included Terry Frost and Terence Coventry. The catalogue is very informative, although constrained by the format and underlying philosophy of the exhibition – a timeline would have been helpful. An essay, ‘An Act of Praise’ Religion and the Work of Barbara Hepworth, by Lucy Kent reveals how taken Hepworth was with the ideas of Christian Science, a philosophy she shared with Ben Nicholson. He had been introduced to it by his first wife, Winifred.

Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World ends on 25 October 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment