Twentysomethings loving in a triangle - how will it end?

The sixth edition of My French Film Festival is running from 18 January to 18 February 2016, making some recent films available on line and in cinemas. The first I posted about was Olivier Jahan’s Les Châteaux de sable (Sand Castles). The second is Jérôme Bonnell’s A trois on y va (All about them)

At the start of Jérôme Bonnell’s comedy drama, A trois on y va (literally We go as a trio), Charlotte, a singer and Micha, a biotechnician, are setting up home in Lille. Micha starts to get interested in Charlotte's lawyer friend Mélodie without realising just what sort of friendship they have. Surely, sooner or later, the deceptions involved are going to become apparent - then what will happen?

Anaïs Demoustier (Claire in François Ozon’s The New Girlfriend last year) is well-cast as the quick-thinking Mélodie.

31 January 2016

29 January 2016

Adam McKay’s ‘The Big Short’

After seeing JC Chandor’s A Most Violent Year a year ago, I sought out the same director’s impressive first feature from 2011, Margin Call. This was the story of how a Wall Street bank nearly crashed in a few days in 2008 told from the viewpoint of those on the inside. Adam McKay’s The Big Short is an account of some of the people, all distinctly unorthodox outsiders, who predicted the same crash well in advance and eventually profited from doing so. It draws on Michael Lewis’s nonfiction book, The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine.

Because of the film’s subject, the director needed to provide explanations of sub-prime mortgages, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and the like and what shorting them on a large scale (the big short, indeed) involved. I had some idea of what had happened in 2008 (though, for example, the existence of CDOs-squared was new to me), so I can’t judge how enlightening metaphorical descriptions from actresses in bubble baths and celebrity cooks are to anyone coming to it all for the first time. (A much drier account can be found here - you might want to stop when you get to “The generational problem” - and there are some recommendations for further reading here). Alex von Tunzelmann, in an article in the Guardian, has looked at the historical accuracy of The Big Short and concluded that it provides “a solid historical explanation of the subprime crisis” though she also points out that most of the characters:

The pub in Exmouth (SW England) where Rickert sets up his laptop was unconvincing: wi-fi in 2007, the other customers spoke Estuary, not Devonshire, English and while they may well dislike bankers now, they probably would have been as blissfully ignorant as the rest of us then!

Because of the film’s subject, the director needed to provide explanations of sub-prime mortgages, collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and the like and what shorting them on a large scale (the big short, indeed) involved. I had some idea of what had happened in 2008 (though, for example, the existence of CDOs-squared was new to me), so I can’t judge how enlightening metaphorical descriptions from actresses in bubble baths and celebrity cooks are to anyone coming to it all for the first time. (A much drier account can be found here - you might want to stop when you get to “The generational problem” - and there are some recommendations for further reading here). Alex von Tunzelmann, in an article in the Guardian, has looked at the historical accuracy of The Big Short and concluded that it provides “a solid historical explanation of the subprime crisis” though she also points out that most of the characters:

… have been semi-fictionalised and renamed. Michael Burry (Christian Bale) really was a stock market investor at Scion Capital; he wore no shoes and listened to thrash metal in the office. Mark Baum (Steve Carell) is based on hedge fund manager Steve Eisman; the movie keeps his Jewish background and straight talking. Jared Vennett (Ryan Gosling) is based on Deutsche Bank bond salesman Greg Lippmann: “He wore his hair slicked back, in the manner of Gordon Gekko,” wrote Lewis, “and the sideburns long, in the fashion of an 1820s Romantic composer or a 1970s porn star.” The film’s Vennett sports disappointingly inadequate sideburns but has a penchant for the same braggadocio as Lippmann. Ben Rickert (Brad Pitt) is based on Ben Hockett, and has a similar apocalyptic outlook.Carell, Gosling and Pitt all play their parts to the full. Burry’s wacky character offers Bale the scope to impress at the time but Carrell’s Baum and Pitt’s Rickert, both difficult men with some moral scruples, will probably linger in one’s memory longer:

We live in an era of fraud in America. Not just in banking, but in government, education, religion, food. Even baseball... (Baum)

If we're right, people lose homes. People lose jobs. People lose retirement savings, people lose pensions. You know what I hate about fucking banking? It reduces people to numbers. Here's a number - every 1% unemployment goes up, 40,000 people die, did you know that? (Rickert)None of these characters are particularly admirable, and most of them could be regarded as being as greedy as the rest of the financial services industry, but they are possessed of a steely determination to be proved right and the majority wrong. I thought one of the best scenes was the meeting in the ratings agency. It’s a long film and frantic at times, presumably thought necessary to convey the atmosphere of Wall Street and New York – I’m sure a Basquiat appeared for a few seconds for no particular reason.

The pub in Exmouth (SW England) where Rickert sets up his laptop was unconvincing: wi-fi in 2007, the other customers spoke Estuary, not Devonshire, English and while they may well dislike bankers now, they probably would have been as blissfully ignorant as the rest of us then!

26 January 2016

Olivier Jahan’s ‘Les Châteaux de sable’

Can’t live with him, can’t live without him …

The sixth edition of My French Film Festival is running from 18 January to 18 February 2016, making some recent films available on line and in cinemas. The first I’ve seen is Olivier Jahan’s Les Châteaux de sable (Sand Castles).

Éléonore and her ex, Samuel, are spending the weekend at the house in Brittany that she has been left by her father. She is a thirty-something photographer whose career is not going well and she needs to sell the house despite its memories. Samuel is an academic historian writing a doctorate based on a shaky thesis about Hitler and the death of his niece, Geli Raubal. Éléonore and Samuel broke up when she went off with someone else, a mistake as it turned out, but by then he was living with Laure. A local estate agent (realtor), Claire, brings a succession of potential buyers to the house, including Maëlle, who was, unknown to Éléonore, a close friend of her father. The couple’s relationship, their relationship with Claire, Samuel’s with Laure, Éléonore’s with her father and his with Maëlle are all explored over the weekend. Perhaps not surprising then that there is extensive use of explanatory voice-overs on the way to finding out if anyone buys the house and whether Éléonore will be seeing Samuel again.

The house is in the Côtes d’Armor department on the north coast of Brittany at Lezardrieux. As Claire explains during the film, the singer-songwriter George Brassens lived there – one of his songs is Les Châteaux de sable. Anyone who enjoyed the late Eric Rohmer’s films will probably like Jahan’s perhaps more melancholic tale. Emma de Caunes in the part of Éléonore provides a convincing portrayal of a young woman who knows she is at a turning point in her life.

The sixth edition of My French Film Festival is running from 18 January to 18 February 2016, making some recent films available on line and in cinemas. The first I’ve seen is Olivier Jahan’s Les Châteaux de sable (Sand Castles).

Éléonore and her ex, Samuel, are spending the weekend at the house in Brittany that she has been left by her father. She is a thirty-something photographer whose career is not going well and she needs to sell the house despite its memories. Samuel is an academic historian writing a doctorate based on a shaky thesis about Hitler and the death of his niece, Geli Raubal. Éléonore and Samuel broke up when she went off with someone else, a mistake as it turned out, but by then he was living with Laure. A local estate agent (realtor), Claire, brings a succession of potential buyers to the house, including Maëlle, who was, unknown to Éléonore, a close friend of her father. The couple’s relationship, their relationship with Claire, Samuel’s with Laure, Éléonore’s with her father and his with Maëlle are all explored over the weekend. Perhaps not surprising then that there is extensive use of explanatory voice-overs on the way to finding out if anyone buys the house and whether Éléonore will be seeing Samuel again.

The house is in the Côtes d’Armor department on the north coast of Brittany at Lezardrieux. As Claire explains during the film, the singer-songwriter George Brassens lived there – one of his songs is Les Châteaux de sable. Anyone who enjoyed the late Eric Rohmer’s films will probably like Jahan’s perhaps more melancholic tale. Emma de Caunes in the part of Éléonore provides a convincing portrayal of a young woman who knows she is at a turning point in her life.

25 January 2016

Fiona Banner at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

This exhibition ended in Birmingham on 17 January but will be in Nürnberg, Germany from March to May 2016.

SCROLL DOWN AND KEEP SCROLLING at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham was, according to Fiona Banner, the artist whose work it featured, “… not a survey – more of an anti-survey. A survey suggests something objective, historical, and fixed. This is subjective; nothing else is possible.” My first encounter with her work back in 2010 was difficult to avoid at Tate Britain, the Duveen Commission that year being Harrier and Jaguar, an installation of two decommissioned fighter aircraft, the former, a Sea Harrier, suspended from the ceiling (below left). Both would later be melted down as Harrier and Jaguar Ingots (2012, below right):

More recently, a 2008 neon of hers, Brackets (An Aside) was one of a couple representing that particular element at Compton Verney’s Periodic Tales. Visiting the Ikon show provided more demonstrations of Banner’s continuing interests in military aircraft and in neons, but the strongest impression it left was of her long-term preoccupation with words and books, and hence printing, which has led to her recent synthesis of a new typeface, Font, an amalgamation of typefaces she has worked with previously:

An explanation probably best not taken at (type)face value (above top) – and it’s a font (above lower) which marks the entry to the show. This starts with one of the artist’s “wordscapes”, NAM (1997), a transcription of her scene-by-scene account of six films based on the Vietnam War. NAM now comes in several forms: a notoriously ‘unreadable 100-page paperback, a screen print billboard (below) and a coffee table (below foreground):

Another screen print billboard transcription follows, her controversial 2002 Turner Prize entry, Arsewoman in Wonderland (below left), in which she describes a pornographic film of that name. Banner states that:

Then come some neons, including The Bastard Word (2007, below top), Paolo Pellegrin’s photographs of the City of London, commissioned by Banner for the Archive of Modern Conflict and a video from 2007 of an uncomfortable-looking Samantha Morton reading out Banner’s description of the actress, observed when posing for a nude life-drawing.

On the floor above was an impressive demonstration of the Murano glassmaker’s craft, Work 3 (2014, above lower), not with much relationship to the other pieces, except that Banner spends a lot of time up towers like it when setting up wall drawings. Then a room full of items - too many to describe here (below left), but I will pick out a bronze, Unboxing (2012, below right), which, like Work 3, could be interpreted as making a comment about the variance between appearance and substance.

Finally, on the military aircraft theme, notable are Chinook (2013, below) a video of the twin-engined helicopter engaged in an aerobatic display at RAF Waddington, projected alongside a list of the manoueuvres it was undertaking:

and 1909-2015 (2010-15, below) a stack, four metres high, of the annual editions of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft: Apparently, Banner has said that

I was told by one of the gallery attendants that there is a hole drilled through the books - perhaps health and safety considerations required that the inevitability of the collapse was postponed by a concealed pillar.

SCROLL DOWN AND KEEP SCROLLING is, according to Ikon’s Director, Jonathan Watkins, “ … a survey of work by one of the leading lights in the British art scene, at a pivotal moment in her career.” It will be at the Kunsthalle Nürnberg from 24 March to 29 May 2016.

SCROLL DOWN AND KEEP SCROLLING at the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham was, according to Fiona Banner, the artist whose work it featured, “… not a survey – more of an anti-survey. A survey suggests something objective, historical, and fixed. This is subjective; nothing else is possible.” My first encounter with her work back in 2010 was difficult to avoid at Tate Britain, the Duveen Commission that year being Harrier and Jaguar, an installation of two decommissioned fighter aircraft, the former, a Sea Harrier, suspended from the ceiling (below left). Both would later be melted down as Harrier and Jaguar Ingots (2012, below right):

More recently, a 2008 neon of hers, Brackets (An Aside) was one of a couple representing that particular element at Compton Verney’s Periodic Tales. Visiting the Ikon show provided more demonstrations of Banner’s continuing interests in military aircraft and in neons, but the strongest impression it left was of her long-term preoccupation with words and books, and hence printing, which has led to her recent synthesis of a new typeface, Font, an amalgamation of typefaces she has worked with previously:

An explanation probably best not taken at (type)face value (above top) – and it’s a font (above lower) which marks the entry to the show. This starts with one of the artist’s “wordscapes”, NAM (1997), a transcription of her scene-by-scene account of six films based on the Vietnam War. NAM now comes in several forms: a notoriously ‘unreadable 100-page paperback, a screen print billboard (below) and a coffee table (below foreground):

Another screen print billboard transcription follows, her controversial 2002 Turner Prize entry, Arsewoman in Wonderland (below left), in which she describes a pornographic film of that name. Banner states that:

This work was always awkward and uncomfortable, and that has been exaggerated because of the changing nature, context and ubiquity of porn in the internet age. I have installed the work upside down to reflect that and mess with the act of looking, interpreting and reading.

Then come some neons, including The Bastard Word (2007, below top), Paolo Pellegrin’s photographs of the City of London, commissioned by Banner for the Archive of Modern Conflict and a video from 2007 of an uncomfortable-looking Samantha Morton reading out Banner’s description of the actress, observed when posing for a nude life-drawing.

On the floor above was an impressive demonstration of the Murano glassmaker’s craft, Work 3 (2014, above lower), not with much relationship to the other pieces, except that Banner spends a lot of time up towers like it when setting up wall drawings. Then a room full of items - too many to describe here (below left), but I will pick out a bronze, Unboxing (2012, below right), which, like Work 3, could be interpreted as making a comment about the variance between appearance and substance.

Finally, on the military aircraft theme, notable are Chinook (2013, below) a video of the twin-engined helicopter engaged in an aerobatic display at RAF Waddington, projected alongside a list of the manoueuvres it was undertaking:

and 1909-2015 (2010-15, below) a stack, four metres high, of the annual editions of Jane’s All the World’s Aircraft: Apparently, Banner has said that

... the stacking of the books tells the story of the history of flight and with its inevitable collapse exposes the fallacy of a linear approach to history.

I was told by one of the gallery attendants that there is a hole drilled through the books - perhaps health and safety considerations required that the inevitability of the collapse was postponed by a concealed pillar.

SCROLL DOWN AND KEEP SCROLLING is, according to Ikon’s Director, Jonathan Watkins, “ … a survey of work by one of the leading lights in the British art scene, at a pivotal moment in her career.” It will be at the Kunsthalle Nürnberg from 24 March to 29 May 2016.

19 January 2016

Steven Spielberg’s ‘Bridge of Spies’

Can the normal considerations about spoilers apply to this film? There may be some people who will read this but not know what happened at the Glienicke Bridge –so look away now!

Bridge of Spies’ plot is easy to describe. In 1957, Rudolf Abel, a Soviet agent in the USA is arrested by the FBI. He is defended by, apparently, a small-time New York insurance lawyer, James Donovan, who, in the absence of anyone else, is prepared to take the case on. By the time the appeal reaches the Supreme Court in Washington, Donovan has suggested not applying the death penalty in Abel’s case so that he could be exchanged for any American agent caught by the Soviets at some future time. Soon an American Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft operated by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is shot down over the USSR and its pilot, Gary Powers, is captured. With the CIA looking over his shoulder, Donovan negotiates the exchange of Powers for Abel in Berlin and secures the release of an American student, Frederic Pryor, at the same time.

As might be expected of Spielberg, Bridge of Spies is handsomely filmed, the recreation of the Berlin Wall and the shooting-down of the U-2 particularly so, and is sure to make Americans feel good about themselves. And, of course, they should, for example the treatment in prison that Abel received would certainly have been far better than that meted out to Powers by the Russians. It was well acted with Tom Hanks as a stolid Donovan and a deservedly Oscar-nominated Mark Rylance as Abel.

But I came away feeling that the film was long enough to have carried a little more complexity and respect for historical accuracy and inferior in that regard to Spielberg’s Lincoln. Not so much the “that type of Buick only came out in 1966” or “Powers’ U-2 was too early to have that particular bulge” carping at details of authenticity, or even the fact that Donovan’s overcoat wasn’t actually stolen, nor was his home shot at - dramatic licence after all. More attention could have been paid to dates and the passage of time between Abel’s arrest and the exchange. But, although there was a mention of Donovan having been an assistant to the US prosecutor at the Nuremburg Trials, his wartime service as General Counsel at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a key precursor to the CIA, was a major and misleading omission. After the war Donovan became a partner in his own New York law firm. He was hardly the small time hero the film implies him to be. If he had not died in 1970 at the age of 53, he would surely have served his country and his government again after his work in Cuba.

Probably less significant is the fact that Powers had left the USAF and as a U-2 pilot was a civilian employee of the CIA. As for Pryor, now an emeritus professor, he recently commented “Well, I enjoyed the movie. “It was good. But they took a lot of liberties with it.” And his exchange “… didn’t happen like it did in the movie at all.” As an aside to Pryor’s article and the game between the Russians and the East Germans to which he refers, as does the film, the map below of occupied Berlin and its four sectors might be of interest. The Glienecke Bridge was between the US sector of Berlin and the surrounding East Germany, Checkpoint Charlie between the US and Soviet sectors.

There are some particular points for a British audience to note, apart from Rylance’s performance:

Bridge of Spies’ plot is easy to describe. In 1957, Rudolf Abel, a Soviet agent in the USA is arrested by the FBI. He is defended by, apparently, a small-time New York insurance lawyer, James Donovan, who, in the absence of anyone else, is prepared to take the case on. By the time the appeal reaches the Supreme Court in Washington, Donovan has suggested not applying the death penalty in Abel’s case so that he could be exchanged for any American agent caught by the Soviets at some future time. Soon an American Lockheed U-2 reconnaissance aircraft operated by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) is shot down over the USSR and its pilot, Gary Powers, is captured. With the CIA looking over his shoulder, Donovan negotiates the exchange of Powers for Abel in Berlin and secures the release of an American student, Frederic Pryor, at the same time.

As might be expected of Spielberg, Bridge of Spies is handsomely filmed, the recreation of the Berlin Wall and the shooting-down of the U-2 particularly so, and is sure to make Americans feel good about themselves. And, of course, they should, for example the treatment in prison that Abel received would certainly have been far better than that meted out to Powers by the Russians. It was well acted with Tom Hanks as a stolid Donovan and a deservedly Oscar-nominated Mark Rylance as Abel.

But I came away feeling that the film was long enough to have carried a little more complexity and respect for historical accuracy and inferior in that regard to Spielberg’s Lincoln. Not so much the “that type of Buick only came out in 1966” or “Powers’ U-2 was too early to have that particular bulge” carping at details of authenticity, or even the fact that Donovan’s overcoat wasn’t actually stolen, nor was his home shot at - dramatic licence after all. More attention could have been paid to dates and the passage of time between Abel’s arrest and the exchange. But, although there was a mention of Donovan having been an assistant to the US prosecutor at the Nuremburg Trials, his wartime service as General Counsel at the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a key precursor to the CIA, was a major and misleading omission. After the war Donovan became a partner in his own New York law firm. He was hardly the small time hero the film implies him to be. If he had not died in 1970 at the age of 53, he would surely have served his country and his government again after his work in Cuba.

Probably less significant is the fact that Powers had left the USAF and as a U-2 pilot was a civilian employee of the CIA. As for Pryor, now an emeritus professor, he recently commented “Well, I enjoyed the movie. “It was good. But they took a lot of liberties with it.” And his exchange “… didn’t happen like it did in the movie at all.” As an aside to Pryor’s article and the game between the Russians and the East Germans to which he refers, as does the film, the map below of occupied Berlin and its four sectors might be of interest. The Glienecke Bridge was between the US sector of Berlin and the surrounding East Germany, Checkpoint Charlie between the US and Soviet sectors.

There are some particular points for a British audience to note, apart from Rylance’s performance:

- Abel was born William Fisher in Newcastle-upon-Tyne in 1903 and moved to post-revolutionary Russia in 1921.

- The U-2 was flown from UK bases at home and overseas and in the past was piloted by RAF personnel. A U-2 aircraft can be seen in the Imperial War Museum’s American Air Museum collection at Duxford. Late models have flown into RAF Fairford in Gloucestershire (SW England) as recently as 2015.

- A Briton, Matt Charman, co-wrote the screenplay for Bridge of Spies with the Coen brothers. He previously worked with Saul Dibb on Suite Française, a film which also put dramatic development ahead of historical particularities.

- And finally, pandering to the odd interests of this blog and a previous post here, it’s just possible that James Donovan is shown in Laura Knight’s The Nuremberg Trial, (below) worked up in situ in 1946 and, coincidentally, held by the Imperial War Museum (in London). He would be in one of the two left-hand rows or on the far side of the court.

18 January 2016

Three Paris Exhibitions: (3) Villa Flora, the Hahnloser Collection

Shows seen last month in a city subdued and uncrowded after les évènements of 13 December

Of the three exhibitions which I saw in Paris in December 2015, I have already posted about Picasso.Mania at the Grand Palais, and Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) at the Musée d’Orsay. This post is about Villa Flora, Les Temps enchantés at the Musée Marmottan Monet. In 1898, Hedy Buhler married Arthur Hahnloser, and from 1906 to 1936 this wealthy Swiss couple formed an art collection for their home, the Villa Flora at Winterthur, near Zurich. About 75 of the collection’s works, paintings and small sculptures, have been lent to the Marmottan – a first European showing and a pleasure to visit.

Initially the Hahnlosers collected contemporary Swiss art and acquired works by Ferdinand Hodler, like Le massif de la Jungfrau vu de Mürren (1911, below top) and Le Lac Léman avec les Alpes savoyardes (c1905, below lower):

Giovanni Giacometti, Maisons ensolleillées à Stampa (1912, below left) and Self-portrait (1907, below right):

and Félix Vallotton (subject of an exhibition in Paris in 2013/14 and one planned for the Royal Academy in London in 2019). The Villa Flora, as well as family portraits by Vallotton, had on show en famille his more challenging Baigneuse de face (1907, below top), and La Blanche et la Noire (1913, below lower):

After 1908, through Vallotton, the Hahnlosers became involved with a wider circle of artists in Paris including Fauves and Nabis and began to acquire works by Pierre Bonnard: Débarcadère (ou l’embarcadère) de Cannes (1928-1934, in the poster above) and La Carafe Provençale (1915, below left):

and Odilon Redon, Le Rêve, (c1908 above right) and Henri Manguin, La Sieste ou Le Rocking-chair, Jeanne (1905, below top) and Albert Marquet, La Fete nationale au Havre (1906 ?-13, below lower):

The Hahnlosers would go on to add depth to the collection by purchasing works by artists they regarded as precursors to the modern works they had already acquired. These include a Cézanne, Portrait de l’artiste (1877-1878, below left) and a Manet, Amazone (1883, below right):

Van Gogh’s Le Semeur (1888, below) would join the collection at a later date having originally been acquired by Arthur’s brother Emil.

Villa Flora, Les Temps enchantés ends on 7 February.

Of the three exhibitions which I saw in Paris in December 2015, I have already posted about Picasso.Mania at the Grand Palais, and Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) at the Musée d’Orsay. This post is about Villa Flora, Les Temps enchantés at the Musée Marmottan Monet. In 1898, Hedy Buhler married Arthur Hahnloser, and from 1906 to 1936 this wealthy Swiss couple formed an art collection for their home, the Villa Flora at Winterthur, near Zurich. About 75 of the collection’s works, paintings and small sculptures, have been lent to the Marmottan – a first European showing and a pleasure to visit.

Initially the Hahnlosers collected contemporary Swiss art and acquired works by Ferdinand Hodler, like Le massif de la Jungfrau vu de Mürren (1911, below top) and Le Lac Léman avec les Alpes savoyardes (c1905, below lower):

Giovanni Giacometti, Maisons ensolleillées à Stampa (1912, below left) and Self-portrait (1907, below right):

and Félix Vallotton (subject of an exhibition in Paris in 2013/14 and one planned for the Royal Academy in London in 2019). The Villa Flora, as well as family portraits by Vallotton, had on show en famille his more challenging Baigneuse de face (1907, below top), and La Blanche et la Noire (1913, below lower):

After 1908, through Vallotton, the Hahnlosers became involved with a wider circle of artists in Paris including Fauves and Nabis and began to acquire works by Pierre Bonnard: Débarcadère (ou l’embarcadère) de Cannes (1928-1934, in the poster above) and La Carafe Provençale (1915, below left):

and Odilon Redon, Le Rêve, (c1908 above right) and Henri Manguin, La Sieste ou Le Rocking-chair, Jeanne (1905, below top) and Albert Marquet, La Fete nationale au Havre (1906 ?-13, below lower):

The Hahnlosers would go on to add depth to the collection by purchasing works by artists they regarded as precursors to the modern works they had already acquired. These include a Cézanne, Portrait de l’artiste (1877-1878, below left) and a Manet, Amazone (1883, below right):

Van Gogh’s Le Semeur (1888, below) would join the collection at a later date having originally been acquired by Arthur’s brother Emil.

Villa Flora, Les Temps enchantés ends on 7 February.

15 January 2016

Three Paris Exhibitions: (2) Splendeurs et misères

Shows seen last month in a city subdued and uncrowded after les évènements of 13 December

Of the three exhibitions I saw in Paris in December 2015, I have already posted about Picasso.Mania

at the Grand Palais, and the next will be on Villa Flora at the Musée Marmottan Monet. This post is about Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) at the Musée d’Orsay, an exhibition which will reappear later in 2016 at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, to be called Lichte zeden (Easy Virtue). The Paris title presumably refers to a part of Honoré de Balzac's La Comédie humaine: Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, (The Splendours and Miseries of Courtesans or A Harlot High and Low) published in four parts from 1838-1847. The Musée d’Orsay is not reluctant to take on difficult subjects, their male nude show in 2013 being an example. Splendeurs et misères, examining prostitution, not just in art but as an aspect of the social history of France, is certainly another, a revelation of misery for the many and splendour for a few.

The d’Orsay version addressed five themes and was spread over 15 rooms with numerous pictures and photographs. The first theme, Ambiguity, looked at the position of women, respectable or otherwise, in public places during the daytime and at night in cafés, cabarets and at the opera. Procurement and soliciting were often near the surface at any time of the day, for example in Giovanni Boldini’s En traversant la rue (1873/75, below left) and James Tissot’s La Demoiselle du magasin (1883/85, below right):

Women drinking alone in cafés is a recurrent theme in the art of the time, as in Degas’ L’Absinthe (1875/76, below left) and Manet’s La Prune (1878, below right). Agostina Sagatori au Tambourin (1887, seen earlier in 2015) was on loan from the Van Gogh Museum which also holds Toulouse-Lautrec’s Poudre de riz, (1887).

The cabaret pictures included Lautrec’s Moulin de la Galette (1889, below upper), on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago, and, from the Ny-Carlsberg-Glyptothek Copenhagen, the less well-known M Delaporte au Jardin de Paris (c1893, below lower):

At the opera, Eugène Giraud’s Le Bal de l'Opéra (1866, below top) and Edouard Degas’ Masked Ball at the Opera (1873, below lower) convey the same scene, the latter being far more compelling in its composition:

After Ambiguity, Brothels - more Lautrecs, of course and photography (there are two sections of contemporary photography). Again from Chicago, Courbet’s Mère Grégoire (1855, 57/59, below left) refers to a character from a popular song, the proprietress of a Parisian brothel. An unfamiliar Lautrec from Budapest was Les Dames au réfectoire (1893/5, below right) conveying the unhappy position of the women employed as prostitutes who had to undergo frequent medical checks – a study for Rue des Moulins, (1894), was in this show, but not the final work, now in Washington.

Prostitution operated at all levels of society including the highest (for which abolition would only finally come in 1946). The section, Les Grandes Horizontales, included, as well as a Fauteuil d’Amour (below top), reputedly used by the Prince of Wales in the 1890s in pursuit of entente cordiale, Rolla (1878, below lower) by Henri Gervex:

followed by Manet’s Olympia (1863, below), bought by the French government in 1890, and introducing the final, rather diffuse, sections of the show:

... Prostitution and the imagination and Prostitution and modernity. Lautrec reappeared with the famous Au Moulin Rouge (1892/95, detail in the poster above), again from Chicago, and the Courtauld’s Private Room in the "Le rat mort" (1899, below left) leading on to, among much else, some Picassos from 1901 including Nu aux bas rouges (below right):

Two final images from a show which is informative if not uplifting: Picasso’s La Buveuse d’absinthe (1901, below left) and Kees van Dongen’s Liverpool Lighthouse (1897, below right):

Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) ends on 17 January but will be at the Van Gogh Museum from 19 February to 19 June. Unfortunately, although Professor Richard Thomson from Edinburgh University was one of the curators of the exhibition, it will not be coming to the UK.

POST-EXHIBITION NOTE

If one measure of an exhibition is whether it alters one’s ways of seeing, Splendeurs et misères was a success – as recently Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882, below) in the Courtauld Gallery, London.

And in case anyone should choose to believe that Paris and London were quite different in their mores, The Awakening Conscience (1853, below) by William Holman Hunt clearly shows a man and his mistress, though sanctimoniously overlaid with religious salvation, in keeping with the susceptibilities of Victorian England.

Of the three exhibitions I saw in Paris in December 2015, I have already posted about Picasso.Mania

at the Grand Palais, and the next will be on Villa Flora at the Musée Marmottan Monet. This post is about Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) at the Musée d’Orsay, an exhibition which will reappear later in 2016 at Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum, to be called Lichte zeden (Easy Virtue). The Paris title presumably refers to a part of Honoré de Balzac's La Comédie humaine: Splendeurs et misères des courtisanes, (The Splendours and Miseries of Courtesans or A Harlot High and Low) published in four parts from 1838-1847. The Musée d’Orsay is not reluctant to take on difficult subjects, their male nude show in 2013 being an example. Splendeurs et misères, examining prostitution, not just in art but as an aspect of the social history of France, is certainly another, a revelation of misery for the many and splendour for a few.

The d’Orsay version addressed five themes and was spread over 15 rooms with numerous pictures and photographs. The first theme, Ambiguity, looked at the position of women, respectable or otherwise, in public places during the daytime and at night in cafés, cabarets and at the opera. Procurement and soliciting were often near the surface at any time of the day, for example in Giovanni Boldini’s En traversant la rue (1873/75, below left) and James Tissot’s La Demoiselle du magasin (1883/85, below right):

Women drinking alone in cafés is a recurrent theme in the art of the time, as in Degas’ L’Absinthe (1875/76, below left) and Manet’s La Prune (1878, below right). Agostina Sagatori au Tambourin (1887, seen earlier in 2015) was on loan from the Van Gogh Museum which also holds Toulouse-Lautrec’s Poudre de riz, (1887).

The cabaret pictures included Lautrec’s Moulin de la Galette (1889, below upper), on loan from the Art Institute of Chicago, and, from the Ny-Carlsberg-Glyptothek Copenhagen, the less well-known M Delaporte au Jardin de Paris (c1893, below lower):

At the opera, Eugène Giraud’s Le Bal de l'Opéra (1866, below top) and Edouard Degas’ Masked Ball at the Opera (1873, below lower) convey the same scene, the latter being far more compelling in its composition:

After Ambiguity, Brothels - more Lautrecs, of course and photography (there are two sections of contemporary photography). Again from Chicago, Courbet’s Mère Grégoire (1855, 57/59, below left) refers to a character from a popular song, the proprietress of a Parisian brothel. An unfamiliar Lautrec from Budapest was Les Dames au réfectoire (1893/5, below right) conveying the unhappy position of the women employed as prostitutes who had to undergo frequent medical checks – a study for Rue des Moulins, (1894), was in this show, but not the final work, now in Washington.

Prostitution operated at all levels of society including the highest (for which abolition would only finally come in 1946). The section, Les Grandes Horizontales, included, as well as a Fauteuil d’Amour (below top), reputedly used by the Prince of Wales in the 1890s in pursuit of entente cordiale, Rolla (1878, below lower) by Henri Gervex:

followed by Manet’s Olympia (1863, below), bought by the French government in 1890, and introducing the final, rather diffuse, sections of the show:

... Prostitution and the imagination and Prostitution and modernity. Lautrec reappeared with the famous Au Moulin Rouge (1892/95, detail in the poster above), again from Chicago, and the Courtauld’s Private Room in the "Le rat mort" (1899, below left) leading on to, among much else, some Picassos from 1901 including Nu aux bas rouges (below right):

Two final images from a show which is informative if not uplifting: Picasso’s La Buveuse d’absinthe (1901, below left) and Kees van Dongen’s Liverpool Lighthouse (1897, below right):

Splendeurs et misères, images de la prostitution en France (1850-1910) ends on 17 January but will be at the Van Gogh Museum from 19 February to 19 June. Unfortunately, although Professor Richard Thomson from Edinburgh University was one of the curators of the exhibition, it will not be coming to the UK.

POST-EXHIBITION NOTE

If one measure of an exhibition is whether it alters one’s ways of seeing, Splendeurs et misères was a success – as recently Manet’s A Bar at the Folies-Bergère (1882, below) in the Courtauld Gallery, London.

And in case anyone should choose to believe that Paris and London were quite different in their mores, The Awakening Conscience (1853, below) by William Holman Hunt clearly shows a man and his mistress, though sanctimoniously overlaid with religious salvation, in keeping with the susceptibilities of Victorian England.

8 January 2016

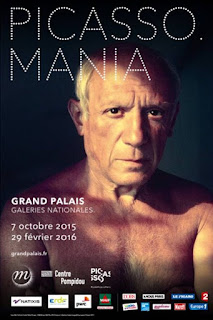

Three Paris Exhibitions: (1) Picasso

Shows seen last month in a city subdued and uncrowded after les évènements of 13 December

While in Paris, I came across an article by Robin Pogrebin in the International New York Times about developments at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Back in 2010, a NYT art critic had described MoMA’s conventional wisdom as “a reluctance to question the linear unspooling of art history according to designated styles that remains the Modern’s core value and its Achilles’ heel”. Now, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture was being quoted as saying that the museum was “reflecting a more widespread shift from thinking in categories – or thinking in so-called canonical narratives – to thinking about multiple histories. Having a sense of curiosity, rather than a desire for pronouncement.” Of the three exhibitions in Paris, the first two, Picasso.Mania at the Grand Palais (described below) and Splendeurs et Misères, can probably be regarded as concerned with multiple histories, the third, Villa Flora (to follow), probably not.

Shows at the Grand Palais aren’t what they used to be. By comparison with their major retrospectives, Georges Braque in 2013 and Edward Hopper in 2012, Picasso.Mania seemed thin stuff. Its thesis was apparently that

and some of the 90th birthday lithographs from 1971:

The most successful of the exhibition themes which followed was probably that given over to cubism – a wall of Picassos:

and then a homage in the form of various works, many by David Hockney, beginning with his Artist and Model (1973/4, below left) and Harlequin (1975, below right):

From the 1980s onwards Hockney explored multiple viewpoints evoking cubism (“a kind of mechanical cubism”) in, for example, Paint Trolley, LA (1985, below top) and Place Ferstenberg, Paris, August 7, 8, 9 (1985, below lower):

More recent Hockney works were The Jugglers, June 24th 2012 (2012, below), 18 films on 18 screens shown over 22 minutes:

and A Bigger Card Players (2015), as at Annely Juda Fine Art, London last summer. After that, the show began to meander. Picasso on screen projected on three walls clips from a wide variety of films (below) in which either the painter or his works or both appear, ranging from Truffaut’s Jules et Jim to Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear to Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

Demoiselles from elsewhere and Guernica, a political icon were both Hamlet without the prince, the originals not being available. Various works inspired by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), included Untitled by Sigmar Polke (2006, below top) and Jeff Koons’ Antiquity (2011, below lower):

Of the works pertinent to Guernica, one of the most interesting to British eyes was Goshka Macuga’s construction, The Nature of the Beast (2009), commissioned by the Whitechapel Gallery in memory of their having exhibited Guernica in 1939 and now owned by the Castello di Rivoli (below left). Part of the work is a glazed circular table which exhibits documents relating to the Spanish civil war and more recent conflicts. I thought the photographs from the Whitechapel’s archive of Clement Attlee in 1939 were thought-provoking (below right) – there is a mention of the Major Attlee Company (sic) in his Wikipedia entry.

After this, a section, It’s a Picasso!, grouped his paintings and prints from the late 1930s and later:

and then some pieces relevant to Picasso and Pop art’s reaction to abstract expressionism including Andy Warhol’s Head (after Picasso) No III (1966, below right top) and Roy Lichtenstein’s Still Life after Picasso (1964, below right lower):

Out of what followed, the impact of Picasso on Jasper Johns’ The Seasons (1985 – 87, Summer below left) with, nearby, Picasso’s Minotaure à la carriole (1936, below right) was notable:

A section covering the media attention Picasso received in his later years was followed by a large display of his late works, some reminiscent of Japanese shunga, seen at Avignon in 1970 and 1973. The final theme was the impact on artists in New York of the Guggenheim’s 1984 Picasso show, for example Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Pablo Picasso) (1984, below):

Picasso.Mania ends on 29 February 2016.

While in Paris, I came across an article by Robin Pogrebin in the International New York Times about developments at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. Back in 2010, a NYT art critic had described MoMA’s conventional wisdom as “a reluctance to question the linear unspooling of art history according to designated styles that remains the Modern’s core value and its Achilles’ heel”. Now, MoMA’s chief curator of painting and sculpture was being quoted as saying that the museum was “reflecting a more widespread shift from thinking in categories – or thinking in so-called canonical narratives – to thinking about multiple histories. Having a sense of curiosity, rather than a desire for pronouncement.” Of the three exhibitions in Paris, the first two, Picasso.Mania at the Grand Palais (described below) and Splendeurs et Misères, can probably be regarded as concerned with multiple histories, the third, Villa Flora (to follow), probably not.

Shows at the Grand Palais aren’t what they used to be. By comparison with their major retrospectives, Georges Braque in 2013 and Edward Hopper in 2012, Picasso.Mania seemed thin stuff. Its thesis was apparently that

After World War II, Picasso became renowned as a modern artistic genius. This public recognition came at a time when contemporary art was once again moving towards “avant-gardism”. This movement’s values, as incarnated by Marcel Duchamp, were in contradiction with Pablo Picasso’s flamboyant subjectivity, media presence and commercial success. As a result, it was only in 1971 that a collective tribute by living artists from different disciplines was organised for the artist’s 90th birthday. In the 1980s, exhibitions showed a new generation of artists how Picasso’s later works were years ahead of his time.A proposition which was not exactly supported by telling visitors that in the 1960s Roy Lichtenstein was inspired by Picasso and that David Hockney was a repeat visitor to the Picasso exhibition at the Tate in 1960. The show made a good initial impression with Sort of Fabulous (2015), a video installation of 18 artists talking about the impact of Picasso on their work, including Jeff Koons, Frank Gehry, Thomas Houseago and Cecily Brown. An unspooling of art history then followed, starting with All hail the artist!, the Self-Portrait of 1901 (below left), borrowed from the Picasso Museum, and some recent images of the artist including Van Pei Ming’s Portrait of Picasso (2009, below centre) and Rudolf Stingel’s Untitled (2012, below right):

and some of the 90th birthday lithographs from 1971:

The most successful of the exhibition themes which followed was probably that given over to cubism – a wall of Picassos:

and then a homage in the form of various works, many by David Hockney, beginning with his Artist and Model (1973/4, below left) and Harlequin (1975, below right):

From the 1980s onwards Hockney explored multiple viewpoints evoking cubism (“a kind of mechanical cubism”) in, for example, Paint Trolley, LA (1985, below top) and Place Ferstenberg, Paris, August 7, 8, 9 (1985, below lower):

More recent Hockney works were The Jugglers, June 24th 2012 (2012, below), 18 films on 18 screens shown over 22 minutes:

and A Bigger Card Players (2015), as at Annely Juda Fine Art, London last summer. After that, the show began to meander. Picasso on screen projected on three walls clips from a wide variety of films (below) in which either the painter or his works or both appear, ranging from Truffaut’s Jules et Jim to Jean-Luc Godard’s King Lear to Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris.

Demoiselles from elsewhere and Guernica, a political icon were both Hamlet without the prince, the originals not being available. Various works inspired by Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), included Untitled by Sigmar Polke (2006, below top) and Jeff Koons’ Antiquity (2011, below lower):

Of the works pertinent to Guernica, one of the most interesting to British eyes was Goshka Macuga’s construction, The Nature of the Beast (2009), commissioned by the Whitechapel Gallery in memory of their having exhibited Guernica in 1939 and now owned by the Castello di Rivoli (below left). Part of the work is a glazed circular table which exhibits documents relating to the Spanish civil war and more recent conflicts. I thought the photographs from the Whitechapel’s archive of Clement Attlee in 1939 were thought-provoking (below right) – there is a mention of the Major Attlee Company (sic) in his Wikipedia entry.

After this, a section, It’s a Picasso!, grouped his paintings and prints from the late 1930s and later:

and then some pieces relevant to Picasso and Pop art’s reaction to abstract expressionism including Andy Warhol’s Head (after Picasso) No III (1966, below right top) and Roy Lichtenstein’s Still Life after Picasso (1964, below right lower):

Out of what followed, the impact of Picasso on Jasper Johns’ The Seasons (1985 – 87, Summer below left) with, nearby, Picasso’s Minotaure à la carriole (1936, below right) was notable:

A section covering the media attention Picasso received in his later years was followed by a large display of his late works, some reminiscent of Japanese shunga, seen at Avignon in 1970 and 1973. The final theme was the impact on artists in New York of the Guggenheim’s 1984 Picasso show, for example Jean-Michel Basquiat’s Untitled (Pablo Picasso) (1984, below):

Picasso.Mania ends on 29 February 2016.

3 January 2016

Lucie Borleteau’s ‘Fidelio: Alice’s Journey’

It's difficult to imagine Fidelio: Alice's Journey, Lucie Borleteau 's first feature, being made in any country but France, where it was released late in 2014 as Fidelio, l’odyssée d’Alice. For a start, the setting is mostly on board a container ship, the Fidelio. Secondly, Alice, a Bretonne like many French sailors, is one of the ship's officers. Thirdly, she is an engineer, good at her job and accepted quite happily by the other officers and ship's crew.

At short notice, 30-year old Alice, played with conviction by Ariane Lebed ( last seen here as one of the villa party in Richard Linklater’s Before Midnight), has to leave her boyfriend, Félix (Anders Danielsen Lie), to take the place of one of Fidelio's engineering officers after his sudden death. Fidelio's captain, Gaël (Melvil Poupaud), was her instructor when she was a student, not just in matters nautical. They revive their affair - infidelity on the part of both. Perhaps not surprisingly, Alice gets a good report and, after some leave with family and boyfriend, returns to the Fidelio as chief engineer. This time, during a longer series of voyages including a call in Senegal, she has a fling with one of the other engineers and starts to read her predecessor's diary. Eventually, the Fidelio, increasingly prone to technical problems, having reached Gdansk is scrapped, a metaphor for Alice's relationship with Félix.

The film is more interesting than I've made it sound. I was surprised how closely involved Alice was shown to be, given her seniority, in tackling Fidelio’s proliferating problems – getting her hands dirty. But la marine marchande could well, for all I know, be under cost pressure to reduce staff and it often has to be all hands to it in a crisis. Although the film is a portrayal of a woman in what was until recently very much a man's world, Alice is not engaged in a tiresome struggle to establish herself in the face of male prejudice, confronting glass ceilings and so on. Instead Borleteau, by following Alice’s life for a few months, reveals the problems both men and women face in being away from home for such long periods. I wonder whether a male director would have been able to take such a frankly honest view of Alice’s sexuality. The UK poster tells us “What happens at sea stays at sea”, but if you think that was introduced with a typical lack of Gallic sophistication, the French equivalent was “Ce qui passe en mer reste en mer”!

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)