There were 11 posts here between 2012 and 2015 labelled “Scottish Independence”, a subject of interest to this blog because it might have led to the relocation to South West England of at least part of the Royal Navy (the deterrent submarine force). Now, 30 months after the decisive No vote of September 2014, the independence issue has been revivified by Brexit and “Scotland being taken out of the EU against our will”, although apparently with no mention by the SNP so far of the nuclear weapons issue.

In 2015, before the EU Referendum, I pointed out that the departure of Scotland (Caledonia to the Romans and the poetically inclined) wouldn’t be such a disaster for what would remain of the UK (Not so Little England) as some Remainers were suggesting. But whether the arrival of Scotland would be welcomed with open arms by some of the remaining 27 EU member countries is another matter, particularly for the Spanish, as this except from a BBC Scotland article by Nick Eardley on 10 March suggested:

What of the Spanish problem?

The SNP's Europe Spokesman was in Madrid earlier this week. He's been one of the party figures travelling around Europe trying to drum up support for Scotland remaining a key player, in spite of Brexit. He says the SNP will remain neutral on Catalonia - arguing the case of the want away Spanish region is different from Scotland. Some will interpret that as a way of trying to make Scottish independence - with full EU membership - more palatable to Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy.

Esetban Pons MEP is vice chair for Mr Rajoy's People's Party in the European Parliament. He told me:

"If Scotland in the future wants to come back they have to begin the procedure as any other country."

But, I asked him, would Spain try and veto Scotland re-entering?

"No because if you are thinking about Catalonia the situation is very very very different to the Scottish situation."

So what constitutes different? The first table below compares the UK and Spain and Scotland and Catalonia and also the impact of the latter pair’s removal on the former pair. The major loss would be Spain’s in terms of population and the economy whereas for the UK it would be more significant in terms of physical area.

The next tables show the impact on the UK and Spain for area and population relative to the other EU countries (the UK will be in the EU until 2019 at least) of these losses and where Scotland and Catalonia would enter.

The final table shows the impact in GDP terms. Five countries out of 28 (Germany, France, UK, Netherlands and Italy) provide nearly 90% of the EU budget. Another five countries are the source of the rest.

However, there is one highly significant difference between Scotland and Catalonia. UK public expenditure per head in England is lower than in Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland, in effect a transfer of resources (currently around £9 billion in the case of Scotland) which has the effect of reducing differences in living standards. By contrast, Catalonia was sending a similar amount to the central Spanish treasury in 2011. Perhaps not so surprising then that there is a continuing majority in Scotland against independence, even post-Brexit, nor that the opposite is the case in Catalonia!

But perhaps a more intriguing aspect of post-Brexit Spanish-UK relations than Scotland vs Catalonia is Catalonia vs Gibraltar. The latter both owe their present status to the Treaty of Utrecht of 1713, as this article from the Guardian in 1977 (recently tweeted by @dentard) reveals:

All statistics from Wikipedia unless otherwise indicated.

Showing posts with label statistics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label statistics. Show all posts

30 April 2017

5 December 2015

The Oldham West and Royton By-election

By-elections are probably over-analysed and over-interpreted but I thought this week’s at Oldham West and Royton was worth looking at. It took place on 3 December 2015 almost exactly seven months after the General Election on 7 May and three months after Jeremy Corbyn became Labour leader. I haven’t seen the results presented anywhere else as below, so offer them here.

The first column shows the Oldham West and Royton results in the General Election (GE) when over 43000 votes were cast. In the By-election (B-E) there were just under 28000 votes, as shown in the fourth column. If these had been cast in exactly the same proportions as at the GE (ie the same reduction in turnout had applied uniformly*) the parties would have had votes as in the second column.

The Green and Monster Raving Loony (MRL) votes can be ignored. What is striking is the consistency of the Liberal Democrat vote between columns two and four and the “poor” showing of the Conservatives. Where did those 2600 Conservative votes go? It seems like about 2000 to Labour and only 800 to UKIP.

Perhaps it’s fair to conclude that quite a few of the voters who are interested enough in politics to turn out for a by-election will vote tactically for whatever is in their own party’s long-term best interest.

Data from Wikipedia.

ADDENDUM 6 DECEMBER

* This was not the only assumption as well as ignoring the Green and MRL. It is possible that some people who turned out for the by-election hadn’t voted in May. More significantly, voters who did turn out for both could have shifted their allegiances in seven months. This diagram indicates the possibilities:

However, I can’t imagine that many May Tories have gone to Labour or Lib Dem. In fact, it seems unlikely that votes would have moved to the Lib Dems in any number from either of the other parties. Hence only the heavy arrows in the diagram,seem to provide a plausible explanation for what happened.

I don't know if the data is available, but it would be very interesting to see the numbers of postal votes, GE and B-E, broken out by party.

The first column shows the Oldham West and Royton results in the General Election (GE) when over 43000 votes were cast. In the By-election (B-E) there were just under 28000 votes, as shown in the fourth column. If these had been cast in exactly the same proportions as at the GE (ie the same reduction in turnout had applied uniformly*) the parties would have had votes as in the second column.

The Green and Monster Raving Loony (MRL) votes can be ignored. What is striking is the consistency of the Liberal Democrat vote between columns two and four and the “poor” showing of the Conservatives. Where did those 2600 Conservative votes go? It seems like about 2000 to Labour and only 800 to UKIP.

Perhaps it’s fair to conclude that quite a few of the voters who are interested enough in politics to turn out for a by-election will vote tactically for whatever is in their own party’s long-term best interest.

Data from Wikipedia.

ADDENDUM 6 DECEMBER

* This was not the only assumption as well as ignoring the Green and MRL. It is possible that some people who turned out for the by-election hadn’t voted in May. More significantly, voters who did turn out for both could have shifted their allegiances in seven months. This diagram indicates the possibilities:

I don't know if the data is available, but it would be very interesting to see the numbers of postal votes, GE and B-E, broken out by party.

25 November 2015

Not so Little England

The December 2015 issue of Prospect magazine seems particularly exercised by the possibility that the UK could leave the European Union. Anatole Kaletsky tells readers that “Leaving Europe could be the biggest diplomatic disaster since losing America” – An ugly divorce. Peter Kellner, President of pollster YouGov, warns that “It cannot be taken for granted that voters will keep Britain in the EU” and Edward Docx (Word ® users should resist reading that as edward.docx) thinks that the “in” campaign is faltering, while the “out” campaign has the benefit of Dominic Cummings, who he describes as “ferocious, committed, unafraid, serious, passionate and utterly certain of his cause”. In his article, called The problem with the EU Debate? The “In” campaign… and the “out” campaign on the Prospect website and Nigel Farage’s Dream in the magazine*, Docx warns:

In terms of area, he clearly has a point as the table above shows. During the discussion of Scottish independence in 2014, rUK, (r meaning rump, residual or ‘rest of’), was used rather than Little England, so for brevity I will use it here. rUK has only 68% of the area of the present UK, something which would be reflected in comparisons with the other major EU countries (and the USA):

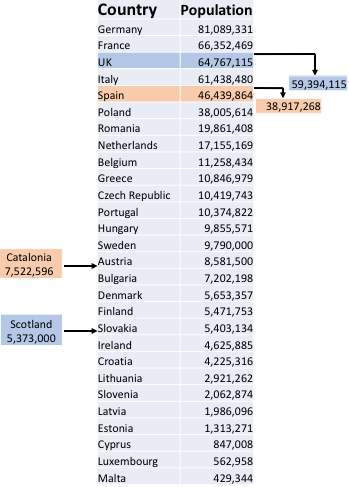

The UK is the 8th largest EU country (of 28) in terms of area, between Italy and Romania. Curiously, rUK would still have been 9th between Romania and Greece. Scotland would be 15th between the Czech Republic (up to 14th in rUK’s absence) and Ireland. However, in population terms, because Scotland has only 8% of the UK’s people, the difference is rather different, as the next table shows:

So, within the EU, where UK is 3rd largest between France and Italy, rUK would have only dropped to 4th between Italy and Spain. Scotland on its own in the EU would be 19th between Slovakia (up to 18th in rUK’s absence) and Ireland.

Another way of presenting these conclusions is to plot population size against area as below. This shows that rUK would have remained one of the handful of EU countries with a population over 20 million, while Scotland would join the ‘shrapnel’ of over 20 smaller ones. Of course, the disproportionate influence of these countries in terms of their population is an important aspect of the EU’s democratic deficit. It might also explain in part why EU membership would be so attractive to an independent Scotland.

While on the subject of population, the UK Office for National Statitics (ONS) has recently published its projections to 2035. As the table below indicates, if Scotland were to become independent by 2025, the rUK population would be 5.6 million lower than the UK’s would have been. However, by 2035 rUK’s population has increased to the same level as the UK’s had been 10 years earlier.

Even more instructive are the equivalent Eurostat projections out to 2080. By 2050, the UK has become the most populated country in Europe. However, so would be rUK by 2060 – hardly “Little England”. (This table is calculated assuming that Scotland’s population remains at the same percentage of the UK’s from 2030 onwards, whereas the ONS figures show a downwards trend from 2015 onwards). The quality of life in such a densely populated country as rUK (essentially England) will become is also likely to be on a downward trend.

Finally, and probably most importantly for many who will vote in the Brexit referendum: perceptions of the economic benefits of leaving the EU. The chart below, again from Eurostat, shows GDP per capita in PPS**relative to the EU’s overall 100. Many people would expect rUK to be better off than the UK, which now makes net payments to the EU while rUK is making transfers within the UK to Scotland. Conversely, Scots could be expected to be worse off. Perhaps the “in” campaign, rather than worrying about “Little England”, should concentrate on disproving this expectation – if they can get their arguments past Dominic Cummings.

* On Docx’s own website, it’s called Are we Sleepwalking to Brexit?

**According to Eurostat: “Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure for the economic activity. It is defined as the value of all goods and services produced less the value of any goods or services used in their creation. The volume index of GDP per capita in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is expressed in relation to the European Union (EU28) average set to equal 100. If the index of a country is higher than 100, this country's level of GDP per head is higher than the EU average and vice versa. Basic figures are expressed in PPS, i.e. a common currency that eliminates the differences in price levels between countries allowing meaningful volume comparisons of GDP between countries. Please note that the index, calculated from PPS figures and expressed with respect to EU28 = 100, is intended for cross-country comparisons rather than for temporal comparisons."

Make no mistake: in less than a year, Great Britain could be out of the EU and no longer Great or, indeed, Britain. David Cameron’s departure will surely follow Brexit, which will also be followed by Scotland’s attempted split from Britain. The splenetic strain of the Conservative Party will be left running Little England—for that is what we will be—and its business for decades to come will be the treaty-by-treaty renegotiation of our relationship with every other country in the world.Perhaps he’s right, but just how small would this “Little England” be? To answer that, it first has to be defined and presumably for Docx it would consist of the UK less Scotland, that is to say, the countries of England, Wales and Northern Ireland.

In terms of area, he clearly has a point as the table above shows. During the discussion of Scottish independence in 2014, rUK, (r meaning rump, residual or ‘rest of’), was used rather than Little England, so for brevity I will use it here. rUK has only 68% of the area of the present UK, something which would be reflected in comparisons with the other major EU countries (and the USA):

The UK is the 8th largest EU country (of 28) in terms of area, between Italy and Romania. Curiously, rUK would still have been 9th between Romania and Greece. Scotland would be 15th between the Czech Republic (up to 14th in rUK’s absence) and Ireland. However, in population terms, because Scotland has only 8% of the UK’s people, the difference is rather different, as the next table shows:

So, within the EU, where UK is 3rd largest between France and Italy, rUK would have only dropped to 4th between Italy and Spain. Scotland on its own in the EU would be 19th between Slovakia (up to 18th in rUK’s absence) and Ireland.

Another way of presenting these conclusions is to plot population size against area as below. This shows that rUK would have remained one of the handful of EU countries with a population over 20 million, while Scotland would join the ‘shrapnel’ of over 20 smaller ones. Of course, the disproportionate influence of these countries in terms of their population is an important aspect of the EU’s democratic deficit. It might also explain in part why EU membership would be so attractive to an independent Scotland.

While on the subject of population, the UK Office for National Statitics (ONS) has recently published its projections to 2035. As the table below indicates, if Scotland were to become independent by 2025, the rUK population would be 5.6 million lower than the UK’s would have been. However, by 2035 rUK’s population has increased to the same level as the UK’s had been 10 years earlier.

Even more instructive are the equivalent Eurostat projections out to 2080. By 2050, the UK has become the most populated country in Europe. However, so would be rUK by 2060 – hardly “Little England”. (This table is calculated assuming that Scotland’s population remains at the same percentage of the UK’s from 2030 onwards, whereas the ONS figures show a downwards trend from 2015 onwards). The quality of life in such a densely populated country as rUK (essentially England) will become is also likely to be on a downward trend.

Finally, and probably most importantly for many who will vote in the Brexit referendum: perceptions of the economic benefits of leaving the EU. The chart below, again from Eurostat, shows GDP per capita in PPS**relative to the EU’s overall 100. Many people would expect rUK to be better off than the UK, which now makes net payments to the EU while rUK is making transfers within the UK to Scotland. Conversely, Scots could be expected to be worse off. Perhaps the “in” campaign, rather than worrying about “Little England”, should concentrate on disproving this expectation – if they can get their arguments past Dominic Cummings.

* On Docx’s own website, it’s called Are we Sleepwalking to Brexit?

**According to Eurostat: “Gross domestic product (GDP) is a measure for the economic activity. It is defined as the value of all goods and services produced less the value of any goods or services used in their creation. The volume index of GDP per capita in Purchasing Power Standards (PPS) is expressed in relation to the European Union (EU28) average set to equal 100. If the index of a country is higher than 100, this country's level of GDP per head is higher than the EU average and vice versa. Basic figures are expressed in PPS, i.e. a common currency that eliminates the differences in price levels between countries allowing meaningful volume comparisons of GDP between countries. Please note that the index, calculated from PPS figures and expressed with respect to EU28 = 100, is intended for cross-country comparisons rather than for temporal comparisons."

7 November 2015

Superforecasting

I’m going to assume that anyone who reads this post has almost certainly been landed here by Google, and therefore is likely to be familiar with the Good Judgement Project (GJP), the brainchild of Professor Philip Tetlock at the University of Pennsylvania and described in his and Dan Gardner's recently published book, Superforecasting: The Art and Science of Prediction. So I won’t provide a description of the GJP or the book.

Before going any further, I should say that I participated in the last GJP tournament and my score over some 135 questions was undistinguished – well below that of the top 2% who Tetlock defines as superforecasters (SFs). So you are welcome to dismiss anything that follows as sour grapes.

Undoubtedly, the book has been reviewed with enthusiasm in the UK by, among others , John Rentoul (not once, not twice “a terrific piece of work that deserves to be widely read”, but three times), Dominic Cummings (“Everybody reading this could do one simple thing: ask their MP whether they have done Tetlock’s training programme.”), Daniel Finkelstein (“This book shows that you can be better at forecasting. Superforecasting is an indispensable guide to this indispensable activity.”) and Dominic Lawson (“fascinating and breezily written”).

A key point to appreciate about individual SFs is that their capability as forecasters is based not so much on what they know - the forecasting questions range widely, so being a subject matter expert is not an advantage - as the way they set about it.. Nor are SFs mostly in the IQ top 1% (135+) of the population, although they are in the top 20% for intelligence and knowledge (Page 109). However, they “are almost uniformly highly numerate people” (Page 130) and “embrace[d] probabilistic thinking” (Page 152). The other factors in their success and how anyone could set about improving their own forecasting skills is the subject of the book.

SFs, being numerate, will have no problem with the Brier scoring system used by the GJP. Brier scoring may well be an eye-glazing subject for most people, but it is one that ought to be understood if an appreciation of superforecasting is to be more than superficial. Hence the Annex below for anyone interested.

Superforecasting, having more significant issues to address, does not bother the reader with much on the way the Brier score is calculated, but it does feature on pages 167/8 when the importance of objectively updating forecasts in the light of new information is being emphasised. A GJP question being asked in the first week of January 2014 was whether “the number of Syrian refugees reported by the UN Refugee Agency as of 1 April 2014” would be under 2.6 million. This chart* from page 167 shows successive forecasts made by one SF, Tim:

On page 168 the reader is told that “Tim’s final Brier score was an impressive 0.07.” The smaller the Brier Score, the better the forecast, of course. By my reckoning, that is the score which Tim would have received if he had made an initial forecast of 81% probability of the answer to the question being “Yes” and stuck with it. But, as is clear, he started with slightly better than evens in early January and then moved towards certainty in late March, thereby achieving SF status, on this as on many other questions.

But what if the UNRA had needed its forecast in January for planning purposes and a more accurate forecast in March would have been too late? The next chart attempts to break out Tim’s forecasts on a monthly basis.

For January it looks as though Tim’s average probability was about 67% so the Brier Score for this month would have been a 0.22, rather poorer than the glittering 0.07. The GJP methodology is time-independent in the sense that it does not attach a greater value (weighting) to early forecasts as opposed to later ones. It might be interesting to see the effect of some discounting, as in (but opposite in time to) Discounted Cash Flow where early cash flows are valued more highly than late ones. This would seem appropriate if an important driver of a real-world forecast is someone’s need to make decisions well before outcomes are known.

Another time-related aspect of the GJP scoring is the termination date of the question. A scenario from the past might be helpful. On 30 September 1938 the leaders of Britain, France, Germany and Italy signed the Munich Pact allowing German occupation of the Sudetenland. The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, returned to London (above) where he was greeted by enthusiastic crowds and spoke of “peace for our time”. However, Churchill said that “England … has chosen shame, and will get war”. So a GJP question in October 1938 might well have asked “Will Britain and Germany be at war by 31 August 1939?”.

A Chamberlain supporter would have started his (or her) answer at a probability much less than 50%, a Churchill supporter at a substantially higher one. As the events of 1939 unfolded, both parties would probably have increased their estimates. However, when the question closed, the Chamberlain supporter would certainly have had the lower Brier Score. Of course, if the question had been “Will Britain and Germany be at war by 30 September 1939?”, their Brier Scores would have been reversed** and the Churchill supporter’s initial pessimism would have been vindicated. So, depending on the date of the question to within just a few days, a good (ie low) Brier Score can be obtained for questionable judgement in a broader sense. There were 135 questions in the recent GJP tournament, 23 of those ended on 31 May and another 39 between 1 and 10 June, dates which probably have more to do with Penn U’s academic year than geopolitics.

It is probably worth bearing in mind that SFs are people adept at minimising time-independent Brier Scores on questions which terminate on arbitrary dates and that is the basis on which their ability as forecasters has been assessed.

As pointed out earlier, the reviews of Superforecasting have been enthusiastic and keen to see its approach being adopted in business and government. I came across this interesting comment on Forbes/Pharma & Healthcare by an admiring reviewer, Frank David, who works in biomedical R&D:

* I may be taking the chart on page 167 too seriously, but a couple of points. The grey space above a probability of 1 is ,of course, just artistic licence. However, I don’t understand (apart from further artistic licence) why the successive forecasts have been joined by straight lines as shown. Surely a forecast remains extant until it is superseded by the next one, and the forecast line is a series of steps, as shown for January 2014 below?

** US readers, and this blog has a few, may need to be reminded that the UK declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939. Germany declared war on the USA on 11 December 1941.

Only superforecasters working in teams are likely to approach perfection - please let me know by commenting if you spot any mistakes in this post!

ANNEX

The red line is the Brier Score, S, as a function of (1-p), the dotted line for comparison is S = (1-p).

UPDATE 30 JUNE 2016

The Superforecasters' prediction for the UK "Brexit" referendum earlier this month was less than stellar - see this post.

Before going any further, I should say that I participated in the last GJP tournament and my score over some 135 questions was undistinguished – well below that of the top 2% who Tetlock defines as superforecasters (SFs). So you are welcome to dismiss anything that follows as sour grapes.

Undoubtedly, the book has been reviewed with enthusiasm in the UK by, among others , John Rentoul (not once, not twice “a terrific piece of work that deserves to be widely read”, but three times), Dominic Cummings (“Everybody reading this could do one simple thing: ask their MP whether they have done Tetlock’s training programme.”), Daniel Finkelstein (“This book shows that you can be better at forecasting. Superforecasting is an indispensable guide to this indispensable activity.”) and Dominic Lawson (“fascinating and breezily written”).

A key point to appreciate about individual SFs is that their capability as forecasters is based not so much on what they know - the forecasting questions range widely, so being a subject matter expert is not an advantage - as the way they set about it.. Nor are SFs mostly in the IQ top 1% (135+) of the population, although they are in the top 20% for intelligence and knowledge (Page 109). However, they “are almost uniformly highly numerate people” (Page 130) and “embrace[d] probabilistic thinking” (Page 152). The other factors in their success and how anyone could set about improving their own forecasting skills is the subject of the book.

SFs, being numerate, will have no problem with the Brier scoring system used by the GJP. Brier scoring may well be an eye-glazing subject for most people, but it is one that ought to be understood if an appreciation of superforecasting is to be more than superficial. Hence the Annex below for anyone interested.

Superforecasting, having more significant issues to address, does not bother the reader with much on the way the Brier score is calculated, but it does feature on pages 167/8 when the importance of objectively updating forecasts in the light of new information is being emphasised. A GJP question being asked in the first week of January 2014 was whether “the number of Syrian refugees reported by the UN Refugee Agency as of 1 April 2014” would be under 2.6 million. This chart* from page 167 shows successive forecasts made by one SF, Tim:

On page 168 the reader is told that “Tim’s final Brier score was an impressive 0.07.” The smaller the Brier Score, the better the forecast, of course. By my reckoning, that is the score which Tim would have received if he had made an initial forecast of 81% probability of the answer to the question being “Yes” and stuck with it. But, as is clear, he started with slightly better than evens in early January and then moved towards certainty in late March, thereby achieving SF status, on this as on many other questions.

But what if the UNRA had needed its forecast in January for planning purposes and a more accurate forecast in March would have been too late? The next chart attempts to break out Tim’s forecasts on a monthly basis.

For January it looks as though Tim’s average probability was about 67% so the Brier Score for this month would have been a 0.22, rather poorer than the glittering 0.07. The GJP methodology is time-independent in the sense that it does not attach a greater value (weighting) to early forecasts as opposed to later ones. It might be interesting to see the effect of some discounting, as in (but opposite in time to) Discounted Cash Flow where early cash flows are valued more highly than late ones. This would seem appropriate if an important driver of a real-world forecast is someone’s need to make decisions well before outcomes are known.

Another time-related aspect of the GJP scoring is the termination date of the question. A scenario from the past might be helpful. On 30 September 1938 the leaders of Britain, France, Germany and Italy signed the Munich Pact allowing German occupation of the Sudetenland. The British Prime Minister, Neville Chamberlain, returned to London (above) where he was greeted by enthusiastic crowds and spoke of “peace for our time”. However, Churchill said that “England … has chosen shame, and will get war”. So a GJP question in October 1938 might well have asked “Will Britain and Germany be at war by 31 August 1939?”.

A Chamberlain supporter would have started his (or her) answer at a probability much less than 50%, a Churchill supporter at a substantially higher one. As the events of 1939 unfolded, both parties would probably have increased their estimates. However, when the question closed, the Chamberlain supporter would certainly have had the lower Brier Score. Of course, if the question had been “Will Britain and Germany be at war by 30 September 1939?”, their Brier Scores would have been reversed** and the Churchill supporter’s initial pessimism would have been vindicated. So, depending on the date of the question to within just a few days, a good (ie low) Brier Score can be obtained for questionable judgement in a broader sense. There were 135 questions in the recent GJP tournament, 23 of those ended on 31 May and another 39 between 1 and 10 June, dates which probably have more to do with Penn U’s academic year than geopolitics.

It is probably worth bearing in mind that SFs are people adept at minimising time-independent Brier Scores on questions which terminate on arbitrary dates and that is the basis on which their ability as forecasters has been assessed.

As pointed out earlier, the reviews of Superforecasting have been enthusiastic and keen to see its approach being adopted in business and government. I came across this interesting comment on Forbes/Pharma & Healthcare by an admiring reviewer, Frank David, who works in biomedical R&D:

So, companies may be able to nurture more “superforecasters” – but how can they maximize their impact within the organization? One logical strategy might be to assemble these lone-wolf prediction savants into “superteams” – and in fact, coalitions of the highest-performing predictors did outperform individual “superforecasters”. However, this was only true if the groups also had additional attributes, like a “culture of sharing” and diligent attention to avoiding “groupthink” among their members, none of which can be taken for granted, especially in a large organization.“ A busy executive might think “I want some of those” and imagine the recipe is straightforward,” Tetlock wryly observes about these “superteams”. “Sadly, it isn’t that simple.”

A bigger question for companies is whether even individual “superforecasters” could survive the toxic trappings of modern corporate life. The GJP’s experimental bubble lacked the competitive promotion policies, dysfunctional managers, bonus-defining annual reviews and forced rankings that complicate the pure, single-minded quest for fact-based decision-making in many organizations. All too often, as Tetlock ruefully notes, “the goal of forecasting is not to see what’s coming. It is to advance the interest of the forecaster and the forecaster’s tribe,” [original emphasis] and it’s likely many would find it difficult to reconcile the key tenets of “superforecasting” with their personal and professional aspirations.Very likely - “the toxic trappings of modern corporate life” - how true indeed.

* I may be taking the chart on page 167 too seriously, but a couple of points. The grey space above a probability of 1 is ,of course, just artistic licence. However, I don’t understand (apart from further artistic licence) why the successive forecasts have been joined by straight lines as shown. Surely a forecast remains extant until it is superseded by the next one, and the forecast line is a series of steps, as shown for January 2014 below?

** US readers, and this blog has a few, may need to be reminded that the UK declared war on Germany on 3 September 1939. Germany declared war on the USA on 11 December 1941.

Only superforecasters working in teams are likely to approach perfection - please let me know by commenting if you spot any mistakes in this post!

ANNEX

The red line is the Brier Score, S, as a function of (1-p), the dotted line for comparison is S = (1-p).

UPDATE 30 JUNE 2016

The Superforecasters' prediction for the UK "Brexit" referendum earlier this month was less than stellar - see this post.

29 September 2015

Jeremy Corbyn: Getting to 2020

I met Jeremy Corbyn back in 2003 when I was spending a day being educated on the ways of Parliament, which included discussions with MPs. Three of us, perhaps at the time not appreciating what would eventually become memorable, went for a cup of tea with Corbyn in Portcullis House. Casting about for a non-partisan topic, I asked him about ways to improve electoral turnout (it had been down to 59.4% in the 2001 general election). I remember the question but not the answer, so in retrospect it seems unlikely that anything particularly radical was suggested. Twelve years later Corbyn has emerged from relative obscurity and is Leader of the Labour Party and the Opposition and, although it seems unlikely, could become Prime Minister in 2020.

The commentariat are going flat out with Corbyn prognoses. Even before he was elected, Sebastian Payne asked on Spectator Coffee House

Initially the selection was confined to the last 80 years, beginning with George Lansbury who became Labour Leader in 1935 and, because of his pacifist views, is seen as having similarities to Corbyn. Over that period there were 14 men and one woman Leaders ab initio, nine Labour and six Conservative. Three of each party went on to win an election so the success rates are 33% for Labour and 50% for the Tories – success being defined as moving from LoO to PM. However, on examination Attlee’s position is exceptional. Lansbury resigned in October 1938, Attlee becoming Labour leader and losing the general election held a month later. Attlee eventually became PM in 1945 but had ceased to be Leader of the Opposition in February 1942 on appointment as Deputy PM in the wartime coalition.

So while it is useful for some purposes, like age on becoming Leader to include Lansbury and Attlee, comparisons with Corbyn for issues like age at the first subsequent general election are more appropriately made looking at the last 60 years. This is the period since Gaitskell became Labour Leader in 1955 and reduces the selection to 12 men and one woman. Seven of these were Labour and six Conservative with two Labour and three Conservative successes, 29% and 50% respectively.

Age

Age is unarguable and Corbyn is certainly younger starting as LoO at 66 than Michael Foot or George Lansbury but at nearly 71 would be older at the time of the next election (7 May 2020) than any of the 11 of his 13 predecessors who survived to an election. Only two of them were over 60, neither man was successful. (In the last 80 years the only successful LoO older than Corbyn was Churchill at nearly 77 in 1951, but, as an ex-PM, and for other good reasons, there is no comparison).

Time in office

In May 2020, Corbyn would have been Leader longer than any of his predecessors except Heath who was successful. The five successful LoOs were in office slightly longer than the six unsuccessful ones but this masks an interesting difference between the two successful Labour LoOs who were in office for less than three years (2.2 average) and the three Conservatives, all more than four years (4.5 average). One could theorise that the UK media build up Tory LoOs, who thereby benefit from time in office, but conduct a war of attrition against Labour LoOs who do better the sooner they can get to Election day.

Health

Although correlated with age, health is always a matter of speculation. It seems reasonable to assume that if Corbyn has, or has had, any significant medical events and issues, they would have emerged in the media by now. To judge from his appearance, Corbyn does not look particularly young for his age. His not dowsing his hair in dye, like so many other politicians, if anything adds to his “authenticity” – perhaps it will encourage others to stop. He is long-sighted (presbyopia) to judge from the photograph of him looking over the top of his glasses at the TUC audience (below top left), as to be expected at 66. He looks slightly overweight to judge from the St Paul’s photograph of him not singing the National Anthem (below top right) – more than might be expected of a vegetarian, almost teetotal, cyclist. In future it can be assumed that he will be cycling less and making more use of the transport provided for LoOs (below lower) and gain weight.

When he was forming his Shadow cabinet in the House of Commons on 13 September, Corbyn was observed by Darren McCaffrey, Politics Reporter for Sky News:

Corbyn is in the unusual position of a man having to give up his hobbies to work at an age when many others have already done the opposite. Should he become PM, he and a future King Charles could at least have that in common. Until now Corbyn has been doing what he enjoys with the salary and continuity of employment of an MP with a safe seat. His interests seem to revolve around the far left of politics and he has been able to spend his time engaged with like-minded people. As an MP answerable to no-one, certainly not his party’s whips, he has been able to avoid the stresses and conflicts of working life which he would have encountered in white collar employment. Men of his age at his salary level in the real world, if they haven’t already quit, will mostly be about to escape from having to meet the unrealistic aspirations of self-serving senior managers while overcoming the reluctance of subordinates to embark on anything but the mildest change.

It seems likely that nothing in Corbyn’s previous experience (apart from two divorces) will approach the stresses that he will encounter in The Worst Job in British Politics. So far he seems to be avoiding confrontation where possible, for example the first PMQs. If an interviewer, and there have been few so far, raises difficult issues, these are being deflected with vague promises of consultative forums and discussions which will arrive at agreements acceptable to all involved. That sort of obfuscation can only go on for so long. For Corbyn the stress of having to compromise sincere beliefs which have hardly ever been challenged, let alone had to be defended could eventually take its physical toll. Oddly enough, the two Labour predecessors to whom he is most often compared, Foot and Lansbury, lived on to the ages of 96 and 81 respectively. However, two Labour LoOs have died in office, Smith and Gaitskell, at 55 and 56.

Conclusion

As investment funds make clear, past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results – or words to

that effect. This is particularly so when the underlying statistics are so scant. But if Corbyn’s health holds out, and, in the hope that 70 is the new 60 I would not want otherwise, the statistics for previous LoOs in terms of age and time in office are not encouraging for him. Nor is the final table (right) which shows the outcomes for the 13 LoOs depending on their month of taking office, unfortunately September in Corbyn’s case.

On past performance Labour would do well to change Leader about two years before the next election – February 2018 looks a particularly auspicious time for a Corbyn successor, someone in their late 40s, to take office. In the unlikely event that anyone takes previous posts on this blog seriously, it would seem a good idea to select asecond-born middle-born who went to Oxford!

Notes

(a) Died in office 12 May 1994

(b) Resigned 6 November 2003

(c) Died in office 18 January 1963

UPDATE 6 DECEMBER 2015

As far as I know, the first media report about Corbyn’s health which has appeared is the one in the Independent on Sunday (IoS) today, Jeremy Corbyn's allies accuse MPs of 'spreading lies' about Labour leader's health, an exclusive by Tom McTague. What I regard as the relevant extracts are below, but the original is easy to access.

UPDATE 7 FEBRUARY 2016

On 5 February Ken Livingstone appeared for about 15 minutes on RT News Thing. About four minutes in, being pressed as to whether he might become Labour leader after Corbyn, he said:

The commentariat are going flat out with Corbyn prognoses. Even before he was elected, Sebastian Payne asked on Spectator Coffee House

If Jeremy Corbyn is elected Labour leader, how long would he last?and concluded that, if not challenged immediately,

Corbyn would be challenged a few months/years in his leadership. There is one particular flashpoint next year to watch: 5 May 2016. If Labour fails to win the Mayor of London race, loses Wales and fails to make any progress in Scotland, there will be calls for him to go.Dan Hodges in the Daily Telegraph thought that the vote on Trident replacement in March 2016 would be a moment of reckoning (though Corbyn later told Andrew Marr that the vote would possibly be in June). On the other hand, John Rentoul in the Independent thought that the Labour Party

is so denuded of talent that it is hard to see where the succession to Corbyn will come from. Part of the reason for his success is the thinness of the field against him, but look beyond them and behold a wasteland.Andrew Rawnsley in the Observer was full of misgivings:

For the moment, the spectacle of a leader and his top team agreeing to disagree on a host of critical issues at least has the merit of being unusual. It is the price Mr Corbyn is being forced to pay to avoid an immediate civil war with his MPs. It can’t be sustainable. There will be a crunch point between leader and parliamentary party. Then things will get really interesting.but was not inclined to speculate about timescales:

Earlier foolish talk about a rapid attempt to unseat him has evaporated. The thumping scale of his victory means that his opponents within will have to tread very carefully for the moment. Yet the truth can’t be concealed. This leaves Labour MPs more divided than I have ever known them. Divided between those who are convinced that the Corbyn leadership will be an instant disaster and those who reckon it will be more of a slow-burning catastrophe for their party. Then there are those who candidly confess that they have no idea where their party is now going. “I think I know how this will end,” says one. “But I can’t say when.”The Guardian made public Peter Mandelson’s private views that it would be “a long haul”:

Nobody will replace him, though, until he demonstrates to the party his unelectability at the polls. In this sense, the public will decide Labour’s future and it would be wrong to try and force this issue from within before the public have moved to a clear verdict.In the FT Magazine, out just as the Labour party conference started, George Parker and Jim Packard had a long piece, Jeremy Corbyn: how long can he last?, but, not surprisingly, didn’t provide a specific answer. On the one hand:

“We have to give him time to fail and to make it clear to all his supporters that this cannot work,” says one moderate Labour MP. “There can’t be a coup now: we would have blood on our hands.”

… “It’s going to go wrong,” says another senior Blairite former minister. “We just don’t know when.”And on the other:

From David Cameron’s point of view, the longer Corbyn stays in the job the better. … “This is proof that God is a Conservative,” says one Cameron ally. The Cameron/Osborne strategy is to hope that Corbyn remains leader as long as possible and that years of leftwing-inspired chaos will cause irreparable damage to the Labour brand.

… Cameron’s allies ponder whether Corbyn can hack the responsibility, the pressure and the mental strain of his new job and the need for constant accommodation and compromise with his party. “Cameron’s mentally extremely strong and even he can find it tough,” says one friend of the prime minister. “Corbyn’s 66. He’s never faced anything like this.” But Dave Prentis, head of the union Unison, says Corbyn has the stamina to survive the coming months. “He has done 100 rallies this summer. I have seen a man who, wherever he has gone, has shown commitment and fortitude,” he says. “Do I think he has the stamina for this? Yes.”On the totalpolitics website, James Skidmore explained Why Jeremy Corbyn will still be Labour leader in 2020, described the three hurdles any challenger would have to clear and concluded, fairly convincingly:

Essentially, the choice facing moderates now is how much rope do they give Corbyn? Until after the 2016 elections or until after 2020? Your correspondent reckons that when they sit down and think through the process they will leave it to 2020.Given such uncertainty, I thought it might be interesting to look for any statistics which sum up the experiences of past Leaders of the Opposition (Leaders or LoOs hereon). To illuminate Corbyn’s position, comparisons should be made only with those individuals who have sought Leadership as a first step towards possible premiership. This rules out those who have had the office thrust upon them, that is those who have become Prime Minister (PM) by another route and then lost an election, most notably Churchill. Also excluded are interim, if recurrent, Leaders like Harriet Harman.

Initially the selection was confined to the last 80 years, beginning with George Lansbury who became Labour Leader in 1935 and, because of his pacifist views, is seen as having similarities to Corbyn. Over that period there were 14 men and one woman Leaders ab initio, nine Labour and six Conservative. Three of each party went on to win an election so the success rates are 33% for Labour and 50% for the Tories – success being defined as moving from LoO to PM. However, on examination Attlee’s position is exceptional. Lansbury resigned in October 1938, Attlee becoming Labour leader and losing the general election held a month later. Attlee eventually became PM in 1945 but had ceased to be Leader of the Opposition in February 1942 on appointment as Deputy PM in the wartime coalition.

|

| Leader of the Opposition statistics (notes at the end of the post) |

Age

Age is unarguable and Corbyn is certainly younger starting as LoO at 66 than Michael Foot or George Lansbury but at nearly 71 would be older at the time of the next election (7 May 2020) than any of the 11 of his 13 predecessors who survived to an election. Only two of them were over 60, neither man was successful. (In the last 80 years the only successful LoO older than Corbyn was Churchill at nearly 77 in 1951, but, as an ex-PM, and for other good reasons, there is no comparison).

Time in office

In May 2020, Corbyn would have been Leader longer than any of his predecessors except Heath who was successful. The five successful LoOs were in office slightly longer than the six unsuccessful ones but this masks an interesting difference between the two successful Labour LoOs who were in office for less than three years (2.2 average) and the three Conservatives, all more than four years (4.5 average). One could theorise that the UK media build up Tory LoOs, who thereby benefit from time in office, but conduct a war of attrition against Labour LoOs who do better the sooner they can get to Election day.

Health

Although correlated with age, health is always a matter of speculation. It seems reasonable to assume that if Corbyn has, or has had, any significant medical events and issues, they would have emerged in the media by now. To judge from his appearance, Corbyn does not look particularly young for his age. His not dowsing his hair in dye, like so many other politicians, if anything adds to his “authenticity” – perhaps it will encourage others to stop. He is long-sighted (presbyopia) to judge from the photograph of him looking over the top of his glasses at the TUC audience (below top left), as to be expected at 66. He looks slightly overweight to judge from the St Paul’s photograph of him not singing the National Anthem (below top right) – more than might be expected of a vegetarian, almost teetotal, cyclist. In future it can be assumed that he will be cycling less and making more use of the transport provided for LoOs (below lower) and gain weight.

When he was forming his Shadow cabinet in the House of Commons on 13 September, Corbyn was observed by Darren McCaffrey, Politics Reporter for Sky News:

… at the end of a bookshelf-lined corridor, opening up to the members’ lobby and behind a door grandly named Her Majesty’s Official Opposition Whips’ Office, Jeremy Corbyn was holed up. … And again Jeremy emerged, which he seemed to do once every hour, when a toilet break was needed.Needing to urinate that frequently suggests that Corbyn has an enlarged prostate pressing on his bladder. If so, that would be a common condition (BPH) in a 66-year old male.

Corbyn is in the unusual position of a man having to give up his hobbies to work at an age when many others have already done the opposite. Should he become PM, he and a future King Charles could at least have that in common. Until now Corbyn has been doing what he enjoys with the salary and continuity of employment of an MP with a safe seat. His interests seem to revolve around the far left of politics and he has been able to spend his time engaged with like-minded people. As an MP answerable to no-one, certainly not his party’s whips, he has been able to avoid the stresses and conflicts of working life which he would have encountered in white collar employment. Men of his age at his salary level in the real world, if they haven’t already quit, will mostly be about to escape from having to meet the unrealistic aspirations of self-serving senior managers while overcoming the reluctance of subordinates to embark on anything but the mildest change.

It seems likely that nothing in Corbyn’s previous experience (apart from two divorces) will approach the stresses that he will encounter in The Worst Job in British Politics. So far he seems to be avoiding confrontation where possible, for example the first PMQs. If an interviewer, and there have been few so far, raises difficult issues, these are being deflected with vague promises of consultative forums and discussions which will arrive at agreements acceptable to all involved. That sort of obfuscation can only go on for so long. For Corbyn the stress of having to compromise sincere beliefs which have hardly ever been challenged, let alone had to be defended could eventually take its physical toll. Oddly enough, the two Labour predecessors to whom he is most often compared, Foot and Lansbury, lived on to the ages of 96 and 81 respectively. However, two Labour LoOs have died in office, Smith and Gaitskell, at 55 and 56.

Conclusion

|

| Leader of the Opposition Month of taking office and outcome |

As investment funds make clear, past performance is not necessarily indicative of future results – or words to

that effect. This is particularly so when the underlying statistics are so scant. But if Corbyn’s health holds out, and, in the hope that 70 is the new 60 I would not want otherwise, the statistics for previous LoOs in terms of age and time in office are not encouraging for him. Nor is the final table (right) which shows the outcomes for the 13 LoOs depending on their month of taking office, unfortunately September in Corbyn’s case.

On past performance Labour would do well to change Leader about two years before the next election – February 2018 looks a particularly auspicious time for a Corbyn successor, someone in their late 40s, to take office. In the unlikely event that anyone takes previous posts on this blog seriously, it would seem a good idea to select a

Notes

(a) Died in office 12 May 1994

(b) Resigned 6 November 2003

(c) Died in office 18 January 1963

UPDATE 6 DECEMBER 2015

As far as I know, the first media report about Corbyn’s health which has appeared is the one in the Independent on Sunday (IoS) today, Jeremy Corbyn's allies accuse MPs of 'spreading lies' about Labour leader's health, an exclusive by Tom McTague. What I regard as the relevant extracts are below, but the original is easy to access.

Labour’s increasingly bitter civil war has deepened after allies of Jeremy Corbyn accused MPs of “spreading lies” about the 66-year-old’s health in an attempt to destabilise his leadership. Labour’s increasingly bitter civil war has deepened after allies of Jeremy Corbyn accused MPs of “spreading lies” about the 66-year-old’s health in an attempt to destabilise his leadership. …

Sources close to the Labour leader have revealed that he has been forced to reassure MPs in private that he is not going to quit after being made aware of “smears” circulating Parliament about his fitness for the job – including the “categorically untrue” allegation that he briefly “passed out” under stress in his office last month. …

One senior Labour source close to Mr Corbyn told The IoS that he had emerged from the past week strengthened – and demanded an end to personal insults and smears about his health. …

A shadow minister, who did not want to be named, went further – accusing anti-Corbyn MPs of being “prepared to spread lies about Jeremy’s health in order to assist them in their aim” of destroying his leadership. He added: “You can’t get much lower than spreading lies about someone’s health to undermine them and their ideas.

UPDATE 7 FEBRUARY 2016

On 5 February Ken Livingstone appeared for about 15 minutes on RT News Thing. About four minutes in, being pressed as to whether he might become Labour leader after Corbyn, he said:

If Jeremy was pushed under a bus being driven by Boris Johnson, it would all rally behind John McDonnell.Almost at the end of the session he reinforced the point, but less hypothetically:

I keep telling you, it’ll be John McDonnell. If Jeremy was to have a stroke or something like that, it will not be me.For comparison with the table above, John McDonnell was born on 8 September 1951 and would be 68.7 on 7 May 2020.

19 January 2015

Former Prime Ministers – some statistics

What uncertain times these are. In the Independent on Sunday on 18 January, Iain Dale, political commentator and former Conservative politician, provided his prediction of the outcome of the May general election (his website is the primary source). It was based on a painstaking consideration of the circumstances of each of the 650 constituencies in the UK parliament, after drawing together whatever local knowledge, polling evidence and so on that he could find. This approach had served Dale well “when I got the European election results bang on and made the most accurate predictions in Cameron’s Cabinet reshuffle”. On the same day in the Sunday Times, Peter Kellner, political commentator, president of the pollster YouGov and husband of a Labour politician provided his forecast (now on YouGov). Their data is in the table below, my additions in italics:

So we may have four former Prime Ministers, with Cameron joining John Major, Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. Or perhaps there will still be three at the end of May. This set me thinking about the number of ex-PMs over the years, hence the chart on the left from 1870 to the current day.

It turns out that for most of the last 100 years, the presence of three or four ex-PMs has been the norm. There only being one, as was mostly the case from 1945-55, was unusual. Only in Gladstone’s final administration was there none, for four years following Disraeli’s death in 1881. Prime Ministers tend to be long-lived – only one born since 1800 died under 70, Bonar Law, who died soon after leaving office in 1923. The only PM to die in office was Campbell-Bannerman in 1908 at the age of 71.

The mean age at death of the 21 deceased PMs born since 1800 has been just over 81 years, but for the five born and deceased since 1900, just over 88. The latter include one woman, Margaret Thatcher, who died at 87, bringing the average down, contrary to actuarial expectation. Presumably to get the job at all requires a good constitution, but comparison should be made with the life expectancy of upper middle class males (mostly) over 40, not males in general at birth.

On average PMs have lived for 14.8 years after leaving office for the last time (Wilson, Churchill, and Baldwin are among those who returned to office). This becomes 17.2 years if Campbell-Bannerman (see above) and Chamberlain and Bonar Law, who both died within six months of leaving office, are excluded. (The arrows are for Major, above Blair, both to the left of Brown, all on-going of course).

The longest lived was Rosebery – more correctly Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, probably the most interesting PM statistically. At 45 he was the youngest person to become PM until Blair and later Cameron. His period in office was only 15 months and his estate is thought to have been the largest –so far. The younger they enter office, as has increasingly been the case, the younger PMs will be when they leave:

As far as the next election is concerned, there would be nothing surprising about either outcome as PM in terms of the consequent number of ex-PMs. However, it seems very likely that the number will go up over the decades ahead. As the table below shows, despite the impression of premierships having become longer, over successive three decade periods, there have been about the same number of office-holders:

However, if the leaving PMs are getting younger and they live to about 90, there will, before long – probably the late 2020s, be six or even seven ex-PMs to be invited to lunch or dinner with the sovereign!

NOTES

1. Dates of birth, death and office are from Wikipedia.

2. The “quick and dirty” method for dates before 1900 in Excel was used.

3. Photograph at top, 1985: PM Thatcher, ex-PMs Callaghan, Douglas Home, Macmillan, Wilson, Heath (left to right).

4. Second photograph, 2012: PM Cameron, ex-PMs Major, Blair, Brown (left to right), Thatcher was too ill to attend.

5. Any errors will be corrected if provided as comments.

16 October 2014

Boris Johnson’s Body Mass Index

Boris Johnson came out with this to the Daily Telegraph recently:

Unsurprisingly, Johnson’s exact height and weight aren’t immediately available, but his remark above and information from the CelebHeights website can be combined to make an estimate of his BMI. CelebHeights states Johnson’s height as “5ft 9.5in (177 cm)”. Comments there, including some from people who have encountered him, suggest this is about right, 5ft 10in being the maximum likely. Assuming that “almost 17 stone” could, if Johnson were being uncharacteristically modest, be as low as 16.5 stone, “Best and Worst Case” BMIs can easily be calculated:

Unfortunately, even when the lightest/tallest combination is chosen, the resulting BMI is over 33. Although Johnson as Mayor of London has no responsibilities for health, as he pointed out to Andrew Marr on The Marr Show on 12 October:

and so on. According to the The Health Survey for England – 2012 Chapter 10, about a third of English men of Johnson’s age are similarly obese or worse and nearly half are just overweight**:

Now it could be that Johnson, like Wikipedia, is more sceptical about BMI than the NHS:

Like most of us Johnson has changed over the years (right). Unkindly, this brings to mind the lament of Frank Greco, a character in Mark Winegardner’s Godfather sequel, The Godfather's Revenge:

* Some readers may be asking, What is a stone? 14 pounds is the short answer, so a 17 stone man weighs 238 pounds, or 107.95 kg.

** An earlier post contained some international comparisons of BMI. Also, as pointed out there, anyone with a BMI above 30 or below 18.5 should seek medical advice).

Although some people have been kind enough to say I don’t look as though I could conceivably be over 15 stone, I weigh almost 17 stone*.and I wouldn’t have expected him to be quite so heavy either. On the other hand, although I’ve never seen him in the flesh, on the television he does seem a little shorter than many top male politicians who are frequently six-footers or more. This is not a healthy combination, at least as measured by Body Mass Index (BMI).

Unsurprisingly, Johnson’s exact height and weight aren’t immediately available, but his remark above and information from the CelebHeights website can be combined to make an estimate of his BMI. CelebHeights states Johnson’s height as “5ft 9.5in (177 cm)”. Comments there, including some from people who have encountered him, suggest this is about right, 5ft 10in being the maximum likely. Assuming that “almost 17 stone” could, if Johnson were being uncharacteristically modest, be as low as 16.5 stone, “Best and Worst Case” BMIs can easily be calculated:

Unfortunately, even when the lightest/tallest combination is chosen, the resulting BMI is over 33. Although Johnson as Mayor of London has no responsibilities for health, as he pointed out to Andrew Marr on The Marr Show on 12 October:

… Well unfortunately, as you may know, I don’t have direct responsibility for healthcare in this city …he could, if he wished, like anyone else look at the National Health Service’s online BMI healthy weight calculator and enter the Best Case data above for a male of 50 who regularly travels on a bike. He would be told:

and so on. According to the The Health Survey for England – 2012 Chapter 10, about a third of English men of Johnson’s age are similarly obese or worse and nearly half are just overweight**:

Now it could be that Johnson, like Wikipedia, is more sceptical about BMI than the NHS:

For example, a chart may say the ideal weight for a man 5 ft 10 in (178 cm) is 165 pounds (75 kg). But if that man has a slender build (small frame), he may be overweight at 165 pounds (75 kg) and should reduce by 10%, to roughly 150 pounds (68 kg). In the reverse, the man with a larger frame and more solid build can be quite healthy at 180 pounds (82 kg).Johnson certainly is of a solid build but he would still seem to have over 20 kg he could do without. The newer measure of waist-to-height ratio might provide a more comfortable fit, if his waist is no more than 42 in (107 cm, ie 0.6 times height for an over 50). Alternatively Johnson believes that for him in matters corporeal, just as in matters political, the normal rules don’t apply. To be fair, he did encourage all of us to lose weight in an article in the Daily Telegraph in June 2014, If we can’t do it on our own, then let’s lose weight together.

|

| 1987 and 2014 |

When I was young, they said I looked like a Greek God. Now I just look like a goddamn Greek.But most of us, of course, never looked like a Greek God in the first place.

* Some readers may be asking, What is a stone? 14 pounds is the short answer, so a 17 stone man weighs 238 pounds, or 107.95 kg.

** An earlier post contained some international comparisons of BMI. Also, as pointed out there, anyone with a BMI above 30 or below 18.5 should seek medical advice).

7 October 2014

Modelling Neverendum

You might wonder why a blog apparently linked to the part of England which is furthest from Scotland takes any interest in the independence referendum held there on 18 September. Firstly, and obviously, all the regions of England would have been affected had the Yes vote won. Secondly, a particular regional interest was the subject of a post here in 2012, Would Scotland’s Loss be the South West’s Gain. This looked at the possible relocation after Scottish independence of the Royal Navy’s nuclear submarines to SW England, a subject which will be revisited in a future post.

In the days after the referendum, two views seemed to emerge. One, delivered outside 10 Downing Street on the morning after by David Cameron, was that

The turnout, as has been widely pointed out, was remarkably high and unlikely to have been improved upon. So, for Yes to have succeeded, about 192,000 No votes would have had to come across. The main sources of insight as to how this could come about in another referendum at some point in the future are provided by opinion polling.

The polls were not startlingly accurate in their predictions in the run-up to the 2014 vote. In March this year a post here looked at one particular Ipsos-MORI opinion poll in detail. It had shown that at that time those certain to vote were divided 32% Yes, 57% No and 11% undecided. As the September vote approached, opinion polls started to indicate that the Yes/No balance had shifted to be much closer – closer in the polls it turned out, than in the actual result. Afterwards Professor John Cutis in his What Scotland Thinks blog concluded that there had been a systematic problem of underestimating the No vote beforehand. However, two essentially retrospective polls were carried out on referendum day by YouGov and Lord Ashcroft Polls and these had overall results close to the outcome and also provided a breakdown of voting behaviour:

The two polls’ age data is easier to compare graphically, and tends to bear out Salmond’s view of older voters:

The Ashcroft poll also asked:

From this it is clear that nearly half of those who voted think the issue will not remain settled for more than 10 years, though, as in the 2014 referendum, enthusiasm for changing the status quo is less apparent among the older age groups. So what might happen in another referendum in five or ten years’ time? An impossible question to answer but it is possible to make an assessment, albeit crude, as to how demographics might have an effect. After all, the 16 year olds of 2019 are today’s 11 year olds and the 16 year olds of 2024 are today’s 6 year olds, today’s 11 year olds being 21 by then. A key source is Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland produced by National Records of Scotland in June 2014. First of all, their Infographic 1:

This explains why the population of Scotland increased by 14,100 between mid-2012 and mid-2013. Using the data from YouGov quoted in Fig 2 above on voting preferences by place of birth (blue data below) it is possible to make a crude assessment of the voting impact of migration:

There are some obvious flaws. Firstly ‘People’ include children under 16 and secondly immigrant and emigrant preferences may be different from those by place of birth: Scottish No voters may be more outward-looking and therefore be more likely to be found in those leaving for the rest of the UK (RUK) and elsewhere than among their stay-at-home compatriots. There are other uncertainties: how many of those emigrating were originally from outside Scotland, went there and then didn’t like it? However, it isn’t easy to see how the net flow of inward immigrants combined with the pattern of the YouGov data could support hopes of a net increase in the Yes vote over the years ahead.

The ‘natural increase’ of 909 conceals much larger underlying population flows. Figure 5 from the Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland shows the facts of life and death:

(Anyone puzzled by the Male and Female notches at 65/66 should read this post!) Most of the nearly 56,000 deaths each year will be among the older members of the population, who, for this purpose, will be assumed to be over 65. The earlier comparison of No voters by age in the two polls (Figs 2 and 3) suggests that about 65% of the 65+’s are No voters. Table 1 of Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland contains details of Scotland’s age breakdown from which the numbers of new voters in 2019 and 2024 can be predicted (ignoring early deaths and migration). If the voting preferences of the new voters continues to be about 50% No, as the polling seems to suggest, there could be a shift to Yes of about 85,000 after 10 years due to ‘natural change’:

To describe this sort of modelling as simplistic is to be kind. Some of the underlying assumptions have already been made apparent, and there are others such as a lower turnout in future referenda differentiated by preference – fewer Nos, say. Also, the errors in the polls for subgroups are considerable – look at the two polls’ different estimates for Male and Female preferences (Fig 2 above) – and this can only get worse the smaller the subgroup, eg 16-18 year olds. As a sensitivity test (in italics in Fig 8) the assumptions made above can be altered in favour of Yes. If the No support among the group of emerging voters were to fall to 30% (unlikely), and the deaths were assumed to be among the oldest voters, and they had a No preference of, say, 75% (again unlikely, given female relative longevity and No preference), the shift to Yes would increase to about 190,000 – the number that Yes needed in 2014. This assumes, of course, that the majority of those who voted in 2014, who will still be alive in 2024, keep voting the same way and that the immigration/emigration effect in the meantime is nil.

So even if the emerging voters were Yes enthusiasts, it seems likely that a substantial number of those who voted No in 2014 would have to change their minds for Yes to get a majority in 2024. What might lead them to do so? This really is peering into the Scottish mists, but an unsatisfactory 'Devo max' (further devolution to Scotland as promised post-referendum), a successful Eurozone, a sovereign area solution for the Clyde naval base (keeping jobs and not antagonising NATO) all might help, as might Catalan independence.

On the other hand, the concentrated location of the Yes vote in 2014 is now well understood and the Yes vote might fall in those parts of Scotland not green in this map:

- not everyone in Scotland may warm to the prospect of being governed from the Republic of Glasgow.

… now the debate has been settled for a generation or as Alex Salmond has said, perhaps for a lifetime. So there can be no disputes, no re-runs – we have heard the settled will of the Scottish people.But the outgoing SNP leader stated:

… the majority of Scots up to the age of 55 voted for independence, and a majority of Scots over 55 voted against independence … When you have a situation where the majority of a country up to the age of 55 is already voting for independence then I think the writing is on the wall for Westminster.And his likely successor, currently his deputy, Nicola Sturgeon, was quoted by BBC News as saying when launching her bid to replace him:

… the country could only become independent if the electorate backed the move in a referendum. But she did not rule out the possibility of the SNP including a commitment to hold a second referendum in a future election manifesto.The leader of the Scottish Conservatives, Ruth Davidson, subsequently warned that:

The SNP lost. Scotland demonstrated her sovereign will. And yet, people at the top want to run this race again as soon as possible. They want Scotland locked in a cycle of neverendum.So it’s worth looking again at the actual result on 18 September:

|

| Fig 1: Referendum results |

The polls were not startlingly accurate in their predictions in the run-up to the 2014 vote. In March this year a post here looked at one particular Ipsos-MORI opinion poll in detail. It had shown that at that time those certain to vote were divided 32% Yes, 57% No and 11% undecided. As the September vote approached, opinion polls started to indicate that the Yes/No balance had shifted to be much closer – closer in the polls it turned out, than in the actual result. Afterwards Professor John Cutis in his What Scotland Thinks blog concluded that there had been a systematic problem of underestimating the No vote beforehand. However, two essentially retrospective polls were carried out on referendum day by YouGov and Lord Ashcroft Polls and these had overall results close to the outcome and also provided a breakdown of voting behaviour:

|

| Fig 2: Opinion polls post-voting |

|

| Fig 3: No voters by age from polls |

Q.8 If it turns out that a majority has voted NO in the referendum, for how long do you think the question of whether Scotland should be independent or remain in the UK will remain settled?

|

| Fig 4: answers to Q.8 by age |

|

| Fig 5: From Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland |

|

| Fig 6: Possible effect of movements to and from Scotland in Fig 5 |

The ‘natural increase’ of 909 conceals much larger underlying population flows. Figure 5 from the Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland shows the facts of life and death:

|

| Fig 7: From Mid-2013 Population Estimates Scotland |

|

| Fig 8: How 'natural change' might affect No vote |

So even if the emerging voters were Yes enthusiasts, it seems likely that a substantial number of those who voted No in 2014 would have to change their minds for Yes to get a majority in 2024. What might lead them to do so? This really is peering into the Scottish mists, but an unsatisfactory 'Devo max' (further devolution to Scotland as promised post-referendum), a successful Eurozone, a sovereign area solution for the Clyde naval base (keeping jobs and not antagonising NATO) all might help, as might Catalan independence.

On the other hand, the concentrated location of the Yes vote in 2014 is now well understood and the Yes vote might fall in those parts of Scotland not green in this map:

- not everyone in Scotland may warm to the prospect of being governed from the Republic of Glasgow.

5 June 2014

Panda Slapped

Bloggers who use Google as their platform have access to what are described as ‘Stats’. There are a variety of these and they are not always consistent. For example, the totals for a day’s Pageviews by country, browser and operating system are usually close, but rarely identical. In turn the Overview figure for ‘Pageviews today’ may be different again.

But all these discrepancies are small. What is really alarming are the 'Stats' of trends over time – look below at the Pageviews for this blog over the last month: from over 100 a day a month ago to less than half that now. Admittedly there has been only a marginal increase in content – the usual 6 or 7 posts added in the last month - but nothing has been removed from or altered in the 350-plus older posts, some of which are viewed every day.

So what has happened? My guess is that it’s to do with the Panda algorithm which underpins Google searches. Funny old thing, but a Google search doesn’t throw up much information about Panda; Google, it seems, also have a related algorithm called Hummingbird. From what I can make out from the Search Engine Watch website, Panda 4.0 was launched around 20 May:

Something similar has happened before after a tweak to Panda, or maybe Hummingbird, and then the Pageviews slowly climb again, but I’ve not seen such a marked drop off before. As I blog primarily for my own amusement, I’m irritated, but not deterred from continuing as before, after being “Panda Slapped”. Read what this blogger felt he had to do after he had taken a far more severe hit from a previous change to Panda.

UPDATE 6 JULY

As predicted, there are signs of a slow recovery, particularly in the last week or so:

But all these discrepancies are small. What is really alarming are the 'Stats' of trends over time – look below at the Pageviews for this blog over the last month: from over 100 a day a month ago to less than half that now. Admittedly there has been only a marginal increase in content – the usual 6 or 7 posts added in the last month - but nothing has been removed from or altered in the 350-plus older posts, some of which are viewed every day.

So what has happened? My guess is that it’s to do with the Panda algorithm which underpins Google searches. Funny old thing, but a Google search doesn’t throw up much information about Panda; Google, it seems, also have a related algorithm called Hummingbird. From what I can make out from the Search Engine Watch website, Panda 4.0 was launched around 20 May:

The Panda algorithm, which was designed to help boost great-quality content sites while pushing down thin or low-quality content sites in the search results, has always targeted scraper sites and low-quality content sites in order to provide searchers with the best search results possible.Well, this isn’t a scraper site so I guess it’s the low quality content! That, and the fact that I don’t make any money for Google through, for example, Google Play, although this blog is consuming a tiny amount of their resources.

Something similar has happened before after a tweak to Panda, or maybe Hummingbird, and then the Pageviews slowly climb again, but I’ve not seen such a marked drop off before. As I blog primarily for my own amusement, I’m irritated, but not deterred from continuing as before, after being “Panda Slapped”. Read what this blogger felt he had to do after he had taken a far more severe hit from a previous change to Panda.

UPDATE 6 JULY

As predicted, there are signs of a slow recovery, particularly in the last week or so:

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)