Simply put by London’s Royal Academy*, the intention of Rubens and His Legacy Van Dyck to Cézanne is to “bring together masterpieces produced during his lifetime, as well as major works by great artists who were influenced by him in the generations that followed” and to do so “through the lens of six themes: power, lust, compassion, elegance, poetry and violence”.

The show starts with Poetry as landscape and makes a good case for Rubens (1577-1640) as a master for Constable (possibly fresh in visitors’ minds from the V&A), Turner (early, not late as recently at Tate Britain) and Gainsborough; as an example, Rubens’ Landscape with a Rainbow (c 1630, below top) and Constable’s Cottage at East Bergholt (c1833, below lower):

And under the same theme, Rubens’ The Garden of Love (c1635, below top) has its successors, for example Watteau’s Pleasures of the Ball (1715-17, below lower). Given its size, the Rubens is a remarkable loan from the Prado, impressive in colour and composition, but even an admirer of the baroque might wonder about the number of putti.

The Elegance theme is an exploration of Rubens’ portraiture - Portrait of Maria Grimaldi and Dwarf (c1607, below left) - particularly in Genoa where Anthony van Dyck - A Genoese Noblewoman and Her Son (c1626, below right) - would follow him from Antwerp. Reynolds, Lawrence and Gainsborough were the English examples of other portrait painters in sway to Rubens.

Power reflects aspects of Rubens’ access as a diplomat to European monarchy. The RA has provided an informative close-up visual display of his ceiling for the Banqueting House in Whitehall. I’ve only been able to study The Apotheosis of James I (1635 below) previously at a distance - an enjoyable break from the death by PowerPoint going on below. Rubens’ masterpiece was a major influence on Thornhill’s Painted Hall at Greenwich Hospital completed nearly a century later.

Compassion covers the religious works which Rubens’ studio produced in quantity. His St Cecilia (1620, below top) was donated to the Vienna Akademie in 1821, becoming the model for an allegory of music by 23-year old Gustav Klimt (1885, below lower) and given the same name.

This is followed contrastingly by Violence with its striking Tiger, Lion and Leopard Hunt from Rennes (1616, below and in the poster above), inspiring to Delacroix and others:

The show ends with Lust, the label for Rubens’ mythological nudes which reveal his ability to capture figure movement and skin hue, for example Pan and Syrinx (1617 below):

There are numerous works by painters following Rubens’ example – Daumier, Cezanne, Renoir - an examination developed further by La Pelegrina, an accompanying selection by Jenny Saville of “paint made flesh” by painters who, she feels, connect with Rubens, including Picasso, Freud, Bacon, Auerbach, Sarah Lucas and Saville herself.

Rubens and His Legacy continues at the RA until 10 April. Although there are some of Rubens’ masterpieces on show, the ratio of his works to those by his followers, some rather dull, is nearing the acceptable minimum.

* From Royal Academy What’s On Spring 2015

23 February 2015

16 February 2015

WW1 British Art at the IWM

2014’s being the centennial of the outbreak of the First World War (WW1), was an opportunity with obvious appeal for the Political-Media Complex. The BBC even appointed a “centenary controller” in 2013 to oversee the "biggest and most ambitious pan-BBC project ever commissioned". As might be expected, the warning on an archived BBC History webpage, no doubt relegated early on in this grand projet, that “The war that 'would be over by Christmas' dragged on for four long years of bloody stalemate” went unnoticed. But the BBC’s coverage of WW1, once the “1914 Christmas Truce” was over, has turned out to be minimal, although we are promised a return to the Somme and Jutland in 2016. It is, of course, unfair to single out the BBC because most of the media seem to have lost interest in the centennial, although The Times is continuing to draw a 100 year-old item from its archive every day. The politicians are, of course, focussed on the 2015 election and the media has moved on to the 70th anniversary of the ending of WW2.

Most of the big art-related WW1 guns were fired off early too. The popular installation by Paul Cummins and Tom Piper, Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, in the Tower of London moat (above) ended in November 2014, although some of its 888,246 ceramic poppies will go on a UK tour. 888,246 is officially the number of British military fatalities in the war, a number which, by definition, couldn’t have been arrived at before November 1918, so the installation might have been more appropriate for the centennial of the Armistice in 2018. The Great War in Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery ran from 27 February to 15 June, ending well before the centenary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, let alone hostilities. But one exhibition, and probably the most significant art offering of the WW1 centennial, did manage to see out the first winter of the hostilities (a harsh one as shown in Eric Kennington’s oil on glass, The Kensingtons at Laventie, (1915 below), the London Imperial War Museum’s Truth and Memory: British Art of the First World War.

The exhibition was part of the reopening of the IWM last year after refurbishment and is the largest show of British First World War art for almost 100 years. Most of the 120 works come from the museum’s own holdings or Tate Britain’s. The division into Truth and Memory - two slippery entities in any context, let alone war art - was certainly expedient given that the two exhibition areas on the third floor of IWM are separated by the landing. On top of this distinction there is another theme: that the initial artistic response to the war may have been expressed in classical and heroic terms but that modernism turned out to be the more appropriate style for the emerging horrors of trench and aerial warfare. An added complexity in curation was the convoluted nature of the government’s sponsorship of war artists. As recorders their images didn’t always suit the government’s wish to maintain wartime morale, and as memorialists their works turned out to be too large for the accommodation post-War governments were prepared to finance. To quote Waldemar Januszczak (his review of Truth and Memory is the best I’ve seen):

Works by Nevinson and Orpen, for example his Dead Germans in A Trench (1918 below left) and The Mad Woman of Douai (1918 below right) dominate the Truth side of the exhibition. Most of Orpen’s work here is in marked contrast with his portraits at the NPG. He gifted his WW1 works to the nation (in 2005 the IWM’s William Orpen Politics Sex and Death provided an opportunity to see these works in the context of his whole career).

The Memory section of the IWM show seemed to attract fewer visitors when I was there, oddly given that there are major works on show, exciting to see as large originals. Both Nash brothers are well-represented: John Nash’s Oppy Wood, 1917: Evening (1918) and 'Over The Top'. 1st Artists' Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 (1918, below):

and Paul Nash’s We Are Making a New World (1918 below top) and The Menin Road (1919 below lower):

There are also a major works by the Vorticist, Percy Wyndham Lewis, A Battery Shelled (1919, below top) and by Stanley Spencer, Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916 (1919, below lower):

And there are some interesting pictures of life on the home front in hospitals and munitions production. Anna Airey’s Shop for Machining 15-inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow, (1918 below) is a remarkable picture of arduous work by women:

Memory concludes with some very large pieces including Charles Sergeant Jagger’s plaster relief of The Battle of Ypres: The Worcesters at Gheluvelt (1919, below top), Orpen’s controversial To the Unknown British Soldier in France (1921) and, of course, John Singer Sargent’s 2.3 metre-wide Gassed (1919 below lower):

Truth and Memory ends on 8 March, so the opportunity to see some of the finest British 20th century art will be over by Easter, you might say.

Most of the big art-related WW1 guns were fired off early too. The popular installation by Paul Cummins and Tom Piper, Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red, in the Tower of London moat (above) ended in November 2014, although some of its 888,246 ceramic poppies will go on a UK tour. 888,246 is officially the number of British military fatalities in the war, a number which, by definition, couldn’t have been arrived at before November 1918, so the installation might have been more appropriate for the centennial of the Armistice in 2018. The Great War in Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery ran from 27 February to 15 June, ending well before the centenary of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, let alone hostilities. But one exhibition, and probably the most significant art offering of the WW1 centennial, did manage to see out the first winter of the hostilities (a harsh one as shown in Eric Kennington’s oil on glass, The Kensingtons at Laventie, (1915 below), the London Imperial War Museum’s Truth and Memory: British Art of the First World War.

The exhibition was part of the reopening of the IWM last year after refurbishment and is the largest show of British First World War art for almost 100 years. Most of the 120 works come from the museum’s own holdings or Tate Britain’s. The division into Truth and Memory - two slippery entities in any context, let alone war art - was certainly expedient given that the two exhibition areas on the third floor of IWM are separated by the landing. On top of this distinction there is another theme: that the initial artistic response to the war may have been expressed in classical and heroic terms but that modernism turned out to be the more appropriate style for the emerging horrors of trench and aerial warfare. An added complexity in curation was the convoluted nature of the government’s sponsorship of war artists. As recorders their images didn’t always suit the government’s wish to maintain wartime morale, and as memorialists their works turned out to be too large for the accommodation post-War governments were prepared to finance. To quote Waldemar Januszczak (his review of Truth and Memory is the best I’ve seen):

No one was sure where to place it [the IWM], or what to do with the art that might go in it. The original idea was to build a new museum commemorating the war in Whitehall, but that proved too expensive. The art was initially put on show in the Crystal Palace, in Sydenham, where the glass walls proved thunderously inappropriate for the showing of pictures. Next, they took it to South Kensington, to galleries adjoining the Imperial Institute, which stood where Imperial College stands now. Finally, after a further decade of muddling, the Imperial War Museum and its great collection of First World War art was installed in its present home, in the building that used to house the most notorious madhouse in the world, Bethlem Royal Hospital — “Bedlam”.Some of the war artists’ works were passed on to the Tate Gallery, for example CRW Nevinson’s La Mitrailleuse (1915 below left) and Bursting Shell (1915 below right):

Works by Nevinson and Orpen, for example his Dead Germans in A Trench (1918 below left) and The Mad Woman of Douai (1918 below right) dominate the Truth side of the exhibition. Most of Orpen’s work here is in marked contrast with his portraits at the NPG. He gifted his WW1 works to the nation (in 2005 the IWM’s William Orpen Politics Sex and Death provided an opportunity to see these works in the context of his whole career).

The Memory section of the IWM show seemed to attract fewer visitors when I was there, oddly given that there are major works on show, exciting to see as large originals. Both Nash brothers are well-represented: John Nash’s Oppy Wood, 1917: Evening (1918) and 'Over The Top'. 1st Artists' Rifles at Marcoing, 30th December 1917 (1918, below):

and Paul Nash’s We Are Making a New World (1918 below top) and The Menin Road (1919 below lower):

There are also a major works by the Vorticist, Percy Wyndham Lewis, A Battery Shelled (1919, below top) and by Stanley Spencer, Travoys Arriving with Wounded at a Dressing Station at Smol, Macedonia, September 1916 (1919, below lower):

And there are some interesting pictures of life on the home front in hospitals and munitions production. Anna Airey’s Shop for Machining 15-inch Shells: Singer Manufacturing Company, Clydebank, Glasgow, (1918 below) is a remarkable picture of arduous work by women:

Memory concludes with some very large pieces including Charles Sergeant Jagger’s plaster relief of The Battle of Ypres: The Worcesters at Gheluvelt (1919, below top), Orpen’s controversial To the Unknown British Soldier in France (1921) and, of course, John Singer Sargent’s 2.3 metre-wide Gassed (1919 below lower):

Truth and Memory ends on 8 March, so the opportunity to see some of the finest British 20th century art will be over by Easter, you might say.

11 February 2015

Morris and Warhol at Modern Art Oxford

I had thought of calling this post, Jeremy Deller’s Morris and Warhol at Modern Art Oxford, to recognise its auteur. In fact, the show’s full title does the job: Love is Enough: William Morris & Andy Warhol curated by Jeremy Deller. Deller is a conceptual, video and installation artist who won the Turner Prize in 2004 for a film and who regards Morris and Warhol as his greatest artistic influences. He sees similarities between the two as he explained at length to Stuart Jeffries in the Guardian:

Among the Warhols (which include the inevitable images of Jackie, Marilyn et al), I was intrigued by Map of the Eastern U.S.S.R. Missile Bases (below 1985-86):

However, as I pointed out in the post here about the NPG show, Morris’s life and work is permanently on display in various locations in the UK, while Warhol turns up all the time. As for the links between them, the beholder can make their own mind up, there being numerous opportunities for comparison, for example a Morris wallpaper (below left) and Warhol’s Head with Flowers (1958, below right):

But one fairly obvious question is never answered in Deller's show – what, if anything, did Warhol think of his predecessor, Morris?

Love is Enough continues at MAO until 8 March and will be at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery from 25 April to 6 September 2015.

UPDATE 16 FEBRUARY

From Google statistics I know that not everyone who reads this blog has English as their first language. So an explanation may be helpful – there is no such word as “humity”, even though it does appear on page 7 of the MAO’s Exhibition Guide:

A Google search reveals that “humity” is often as a misprint of “humidity” (commonly, it would seem, in queries from cannabis growers and in hotel visitors' reports). We can safely rule out “homity”, an English pie made from potato, onion and leek (enough said):

And being Oxford, you can rule out “humility” and start looking for something much grander – ah, yes “humanity”. The University of Oxford Future of Humanity Institute in the Oxford Martin School, what else?

Both established printmaking businesses, both envisaged art not as something done in lonely garrets but through collaboration. One critiqued the industrial culture of the 19th century; the other parodied the industrial culture of the 20th. Both wanted art to be for the people. Both – and this is where Deller is at his most challenging – were political artists. Come on, Warhol political? “The electric chair? The pictures of race riots? There’s more to him than his trademark blankness.”

Deller takes these politicised Warholian images as parallel to Morris’s political writings almost a century earlier. “Morris wrote furiously about how the crafts skills in India and Malaya were ruined because the British empire wanted cheap mass-produced products. He totally understood the processes and how that affected art making. William Morris was the precursor of modernism.” Really? “He stood for things being beautiful and practical and well made. Bauhaus was a reaction against cheaply made goods. Morris got there long before them.”

He shows me a political pamphlet Morris wrote called A Factory as It Might Be. “Everyone thinks he’s a luddite. He wanted people to have gardens and grow their own vegetables. But Morris didn’t oppose machines: he thought they were good if they took away demeaning labour.” The factory that the English communist dreamed of was not, Deller argues, so very far away from the Factory that Andy Warhol ran in midtown Manhattan.

“Both were very much hoping that work might be idyllic,” says Deller. Did Warhol really care about that? “The working environment he created at the Factory is a norm now for creative people. There’s a flow of people from whom you get ideas that feed into the art. I think that William Morris would be very happy that, in 2014, we live in Warhol’s world, that we don’t work in the kind of factories he hated.” He describes Morris as the Warhol of his day, trying to revolutionise the alienating world of industrial work by the means of, incredibly, soft furnishings and floral wallpaper.And so on. Visitors may or may not be convinced by this line of argument - Richard Derwent in the Daily Telegraph certainly wasn’t:

Nothing I’ve seen in any medium begins to touch the depths of the exhibition Jeremy Deller has put together about what he conceives to be the many points of similarity between two great artists, William Morris and Andy Warhol. But these exist only in his own mind. Virtually every comparison he draws between the two either in the catalogue or in interviews is at best a half-truth, which he then justifies by blatant sophistry.and later called it one of the worst exhibitions of 2014. Perhaps he made the mistake of seeing this show and the Ashmolean’s William Blake on the same day out. But let’s look on the bright side: the exhibition is free and so is the MAO Exhibition Guide with background essays, eg The Relationship Between the Neural Plumbing and the Agape by Dr Anders Sandberg of the Future of Humity Institute – well we are in Oxford. And those of us who are ill-equipped for that level of appreciation and also aren’t desperate to synthesise the two men’s work, can enjoy the show, with its hundred plus items including books and photographs. MAO has a bigger area available than was the case at the recent National Portrait Gallery William Morris exhibition and makes use of it to show the technique of block-printing wallpaper and one of the large Quest for the Holy Grail Tapestries designed by Burne-Jones, Dearle and Morris, The Attainment; The Vision of the Holy Grail to Sir Galahad, Sir Boris and Sir Percival (1895-96, 6th panel below):

Among the Warhols (which include the inevitable images of Jackie, Marilyn et al), I was intrigued by Map of the Eastern U.S.S.R. Missile Bases (below 1985-86):

However, as I pointed out in the post here about the NPG show, Morris’s life and work is permanently on display in various locations in the UK, while Warhol turns up all the time. As for the links between them, the beholder can make their own mind up, there being numerous opportunities for comparison, for example a Morris wallpaper (below left) and Warhol’s Head with Flowers (1958, below right):

But one fairly obvious question is never answered in Deller's show – what, if anything, did Warhol think of his predecessor, Morris?

Love is Enough continues at MAO until 8 March and will be at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery from 25 April to 6 September 2015.

UPDATE 16 FEBRUARY

From Google statistics I know that not everyone who reads this blog has English as their first language. So an explanation may be helpful – there is no such word as “humity”, even though it does appear on page 7 of the MAO’s Exhibition Guide:

A Google search reveals that “humity” is often as a misprint of “humidity” (commonly, it would seem, in queries from cannabis growers and in hotel visitors' reports). We can safely rule out “homity”, an English pie made from potato, onion and leek (enough said):

And being Oxford, you can rule out “humility” and start looking for something much grander – ah, yes “humanity”. The University of Oxford Future of Humanity Institute in the Oxford Martin School, what else?

7 February 2015

Woody Allen’s 'Magic in the Moonlight'

Woody Allen, as is well-known, directs a film every year, some markedly better than others. The first posted about here was the successful Midnight in Paris in 2011. To Rome with Love, good in parts, followed in 2012 and then, in 2013, came Blue Jasmine. This had the considerable advantages of a script deriving from Tennessee Williams and of a performance by Kate Blanchette which won her an Oscar. However, in September 2014 Magic in the Moonlight had such indifferent reviews in the UK that I didn’t bother to go. Now that the film has become easily available in the UK on DVD and online*, it seemed time to find out whether the critics were right.

Magic in the Moonlight begins in Berlin in 1928 with the theatre act of Stanley Crawford (Colin Firth), a professional magician who appears internationally under the stage name of Wei Ling Soo. After the performance he is taken to a nightclub by a fellow magician, a scene which allows a brief homage to Marlene Dietrich (right**). Unfortunately, after this early promise of another Midnight in Paris, things go downhill. Crawford is persuaded to go, under yet another name, to the South of France where some wealthy Americans have fallen under the spell of a young clairvoyant Sophie Baker (Emma Stone). His mission is to expose her as a fraud but when he sets about this task complications ensue.

Firth does as well as he can within the limitations of the plot and Crawford’s stony character, and Stone provides the ambiguity necessary to sustain Baker’s being either a fraud or a true seer. Some of the dialogue about the nature of reality and the conflict of love and rationality is amusing but the plot is lifeless and lacking in humour, like most of the supporting cast. Much of the filming seems to have been done in early morning or early evening and the lighting seems unreal. But no doubt intentionally, the director of A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982) has chosen to set his film in a magical world where observatories are left unlocked, there are impossible reappearances and people travel from the Côte d’Azur to Provence (no more possible than from Cornwall to the West Country or from Rhode Island to New England).

Magic in the Moonlight is at the level of Allen’s lean period from 2000 to 2010, the exception then being Vicky Christina Barcelona. Let’s hope 2015’s Irrational Man will be back on more recent form.

* £9.99 and not really worth it.

** For a clip of Dietrich in von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, see this post from three years ago.

Magic in the Moonlight begins in Berlin in 1928 with the theatre act of Stanley Crawford (Colin Firth), a professional magician who appears internationally under the stage name of Wei Ling Soo. After the performance he is taken to a nightclub by a fellow magician, a scene which allows a brief homage to Marlene Dietrich (right**). Unfortunately, after this early promise of another Midnight in Paris, things go downhill. Crawford is persuaded to go, under yet another name, to the South of France where some wealthy Americans have fallen under the spell of a young clairvoyant Sophie Baker (Emma Stone). His mission is to expose her as a fraud but when he sets about this task complications ensue.

Firth does as well as he can within the limitations of the plot and Crawford’s stony character, and Stone provides the ambiguity necessary to sustain Baker’s being either a fraud or a true seer. Some of the dialogue about the nature of reality and the conflict of love and rationality is amusing but the plot is lifeless and lacking in humour, like most of the supporting cast. Much of the filming seems to have been done in early morning or early evening and the lighting seems unreal. But no doubt intentionally, the director of A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982) has chosen to set his film in a magical world where observatories are left unlocked, there are impossible reappearances and people travel from the Côte d’Azur to Provence (no more possible than from Cornwall to the West Country or from Rhode Island to New England).

Magic in the Moonlight is at the level of Allen’s lean period from 2000 to 2010, the exception then being Vicky Christina Barcelona. Let’s hope 2015’s Irrational Man will be back on more recent form.

* £9.99 and not really worth it.

** For a clip of Dietrich in von Sternberg’s The Blue Angel, see this post from three years ago.

4 February 2015

William Blake at the Ashmolean

William Blake Apprentice and Master at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford aims to provide a chronological account of the life and work of Blake (1757 – 1827), engraver, painter and poet, though, inevitably as an exhibition, it is most informative about the first two of these roles. At the age of 17 Blake entered a seven-year apprenticeship as an engraver after which he studied at the Royal Academy. Zoffany’s painting of the Academy’s Professor of Anatomy, William Hunter MD (c1772 below) indicates the thoroughness of its schooling at the time.

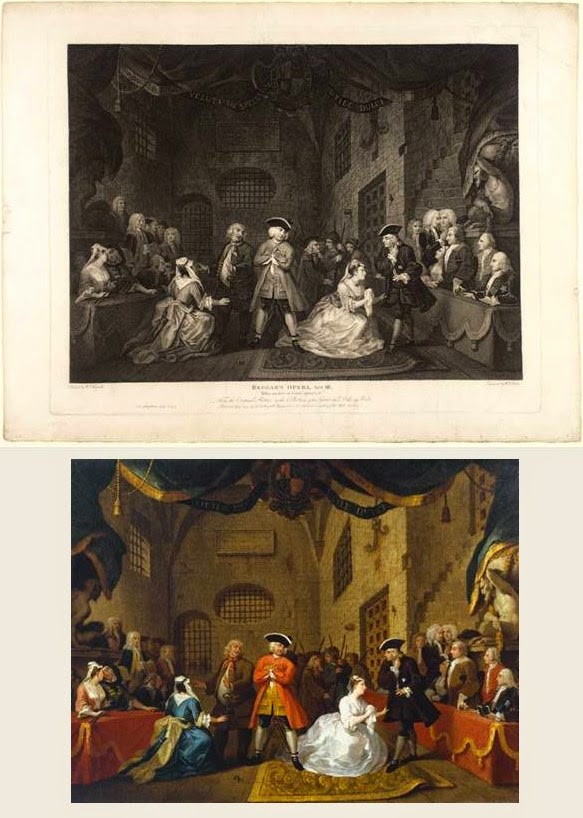

The exhibition is largely chronological and shows how, once developed, Blake’s skill as an engraver brought commercial success, for example his copy, Beggar’s Opera, Act III (1790, below top), of Hogarth’s painting, A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI (1731, below lower).

The exhibition then moves on to Blake’s innovations in printmaking which allowed the integration of text and illustration, eg Laocoon (1826-7, below):

and in hand-coloured relief etching through which he created such memorable images as Los Howl’d from the First Book of Urizen (1796, poster above), Nebuchadnezzar (c1795–1805, below top) and Newton (1795, below lower):

The interpretation of these and other images and their place in his writings is rather beyond the scope of this blog. Blake’s religiosity, mysticism and political views to be found in his writings are specialist areas in their own right. But I did recall this passage from one of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time novels. Nicholas Jenkins (the novels’ narrator) is attending the Victory service held in St Paul’s Cathedral, London in 1945:

William Blake Apprentice and Master ends on 1 March 2015.

The exhibition is largely chronological and shows how, once developed, Blake’s skill as an engraver brought commercial success, for example his copy, Beggar’s Opera, Act III (1790, below top), of Hogarth’s painting, A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI (1731, below lower).

The exhibition then moves on to Blake’s innovations in printmaking which allowed the integration of text and illustration, eg Laocoon (1826-7, below):

and in hand-coloured relief etching through which he created such memorable images as Los Howl’d from the First Book of Urizen (1796, poster above), Nebuchadnezzar (c1795–1805, below top) and Newton (1795, below lower):

The interpretation of these and other images and their place in his writings is rather beyond the scope of this blog. Blake’s religiosity, mysticism and political views to be found in his writings are specialist areas in their own right. But I did recall this passage from one of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time novels. Nicholas Jenkins (the novels’ narrator) is attending the Victory service held in St Paul’s Cathedral, London in 1945:

…We rose to sing Jerusalem.

'Bring me my Bow of burning gold;

Bring me my Arrows of desire;

Bring me my spear; O Clouds unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!'

Was all that about sex too? If so, why were we singing it at the Victory Service? Blake was as impenetrable as Isaiah; in his way, more so. It was not quite such wonderful stuff as the Prophet rendered into Elizabethan English, yet wonderful enough. At the same time, so I always felt, never quite for me. Blake was a genius, but not one for the classical taste. He was too cranky. No doubt that was being ungrateful for undoubted marvels offered and accepted. One often felt ungrateful in literary matters, as in so many others. (The Military Philosophers, page 229)The curator has taken the trouble to recreate the room in Blake’s house in Lambeth (demolished nearly 100 years ago) where he made his prints, complete with a new printing press of the type he used (below left). One imagines that the original would have been well-stained with spilt ink. The show ends with works by some of the younger artists who had become his followers at the end of his life, for example Samuel Palmer’s Landscape with the Repose of the Holy Family (1824–1825, below right).

William Blake Apprentice and Master ends on 1 March 2015.

2 February 2015

JC Chandor’s ‘A Most Violent Year’

A Most Violent Year is set in 1981 in New York where Abel Morales (Oscar Isaac) is an emerging presence in the cutthroat business of distributing heating oil. Just as he is about to close on a real estate deal for a riverside tank facility which would turn him into a major player, his rivals close in. His employees are intimidated, his family are threatened and an ambitious young assistant District Attorney (David Oyelowo) puts him under investigation. Abel’s wife, Anna (Jessica Chastain), keeps the business’s books in the less than rigorous fashion of the time and sector and, coming from a mafia family, has her own views on how to handle the situation. Abel sets out to do better than that, believing that a man “must take the path that is most right” and being totally confident in his ability to do so and in his own powers of leadership. The film is the story of how, rather against the odds, he succeeds and is revealed to be cut out to be much more than a dealer in kerosene. I would be surprised if Chandor doesn’t return before long to the story of Abel Morales .

Abel’s fastidiousness and ambition gives Isaac a chance to reveal his considerable dramatic range, quite a different characterisation from those of Rydal in The Two Faces of January and (Inside) Llewyn Davis. Chastain, notable in Zero Dark Thirty, has a couple of good scenes but the film is primarily about Anna’s husband.

Chandor’s first feature, Margin Call, which he also wrote and directed, was primarily about investment banking at the time of the crash, Wall Street and New York providing the background. This film, his third, is down on the streets and audiences outside the US may not always appreciate the nuances of a scenario firmly embedded in a particular American city (even if they realise that in the US a DA has to run for office). By far the most helpful and informative review of A Most Violent Year which I have read was, perhaps not surprisingly, that in the New Yorker by their David Denby who has been a film reviewer in New York since the 1970s.

Chandor has now started on Deepwater Horizon, a story about the offshore drilling rig disaster in 2010 which had such dire consequences for the UK oil major, BP. It will be interesting to see what line he takes and consequently what British critics decide to make of it.

Abel’s fastidiousness and ambition gives Isaac a chance to reveal his considerable dramatic range, quite a different characterisation from those of Rydal in The Two Faces of January and (Inside) Llewyn Davis. Chastain, notable in Zero Dark Thirty, has a couple of good scenes but the film is primarily about Anna’s husband.

Chandor’s first feature, Margin Call, which he also wrote and directed, was primarily about investment banking at the time of the crash, Wall Street and New York providing the background. This film, his third, is down on the streets and audiences outside the US may not always appreciate the nuances of a scenario firmly embedded in a particular American city (even if they realise that in the US a DA has to run for office). By far the most helpful and informative review of A Most Violent Year which I have read was, perhaps not surprisingly, that in the New Yorker by their David Denby who has been a film reviewer in New York since the 1970s.

Chandor has now started on Deepwater Horizon, a story about the offshore drilling rig disaster in 2010 which had such dire consequences for the UK oil major, BP. It will be interesting to see what line he takes and consequently what British critics decide to make of it.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)