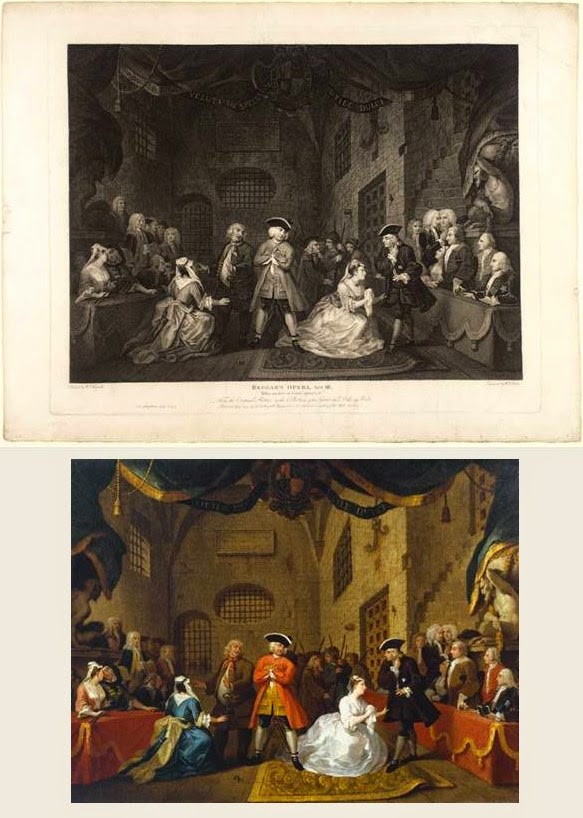

The exhibition is largely chronological and shows how, once developed, Blake’s skill as an engraver brought commercial success, for example his copy, Beggar’s Opera, Act III (1790, below top), of Hogarth’s painting, A Scene from ‘The Beggar’s Opera’ VI (1731, below lower).

The exhibition then moves on to Blake’s innovations in printmaking which allowed the integration of text and illustration, eg Laocoon (1826-7, below):

and in hand-coloured relief etching through which he created such memorable images as Los Howl’d from the First Book of Urizen (1796, poster above), Nebuchadnezzar (c1795–1805, below top) and Newton (1795, below lower):

The interpretation of these and other images and their place in his writings is rather beyond the scope of this blog. Blake’s religiosity, mysticism and political views to be found in his writings are specialist areas in their own right. But I did recall this passage from one of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time novels. Nicholas Jenkins (the novels’ narrator) is attending the Victory service held in St Paul’s Cathedral, London in 1945:

…We rose to sing Jerusalem.

'Bring me my Bow of burning gold;

Bring me my Arrows of desire;

Bring me my spear; O Clouds unfold!

Bring me my chariot of fire!'

Was all that about sex too? If so, why were we singing it at the Victory Service? Blake was as impenetrable as Isaiah; in his way, more so. It was not quite such wonderful stuff as the Prophet rendered into Elizabethan English, yet wonderful enough. At the same time, so I always felt, never quite for me. Blake was a genius, but not one for the classical taste. He was too cranky. No doubt that was being ungrateful for undoubted marvels offered and accepted. One often felt ungrateful in literary matters, as in so many others. (The Military Philosophers, page 229)The curator has taken the trouble to recreate the room in Blake’s house in Lambeth (demolished nearly 100 years ago) where he made his prints, complete with a new printing press of the type he used (below left). One imagines that the original would have been well-stained with spilt ink. The show ends with works by some of the younger artists who had become his followers at the end of his life, for example Samuel Palmer’s Landscape with the Repose of the Holy Family (1824–1825, below right).

William Blake Apprentice and Master ends on 1 March 2015.

No comments:

Post a Comment