Veronese

At the National Gallery, Veronese Magnificence in Renaissance Venice fully lived up to its title. Paolo Bazaro (also Caliari), who came from Verona and so was known as Veronese, lived from 1528 to 1588. The time line on the way into the exhibition helpfully explained that these years spanned the establishment of the Church of England, the birth of Shakespeare and the Spanish Armada. Then a chronological sequence of fifty works followed his artistic progress from his home town to Vicenza, Mantua and, from1555, Venice. Some of these were being reunited at the National Gallery, which has ten Veroneses of its own, for the first time in many years.

Many of the pictures were of religious scenes and intended to decorate churches (12 altarpieces), some were based on classical mythology and a few were portraits. In these, Veronese carefully documented the opulent costumes of his wealthy aristocratic subjects, but still managed to convey something of the sitter's personality, as for example in Portrait of a Lady, known as the 'Bellamy Nani' (about 1560-5, below).

I suppose that fewer of us than would have been the case in the past have the biblical awareness to appreciate immediately the content of, say, Christ and the Centurion (about 1750, below)

or to know that a jar is associated with Mary Magdalene. Fortunately, the curators compensated for this in their guide. Some of the exhibits were larger than any I had seen before in a temporary exhibition. For example, The Martyrdom of Saint George (about 1565, below), removed from the church of San Giorgio in Braida, Verona for only the second time in its existence, is approximately 4m by 3m.

The curators and lenders must have faced considerable problems in ensuring its secure and safe transit. Knowing all too little classical mythology, I was also grateful for being provided with brief accounts of works like Perseus and Andromeda (1575-80, below).

However ill-equipped some of us might be to appreciate the biblical and classical references, the details in the paintings revealed an unfamiliar and fascinating 16th century world full of consiglieri, servants, horses, dogs and monkeys. Sea-borne trade was the economic basis of Venice’s wealth and I liked the two Allegories of Navigation, about 1555-60, one with a Cross-Staff (left) and the other with an Astrolabe (right).

No doubt like many others, I left the exhibition thinking it was time to visit Northern Italy, particularly Venice, again. A complementary exhibition, Paolo Veronese L'illusione della realtà, will be at the Museo di Castelvecchio, Verona, from 5 July – 5 October 2014).

Great War Portraits

The Great War in Portraits at the National Portrait Gallery was a small and rather crowded show scheduled to end before the centenary of the start of World War 1 had been reached, or even that of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Perhaps the current Director of the NPG wanted to do something on the subject before he leaves, or it was a Whitehall priority. I can't believe it will be the Gallery's last word on the War before 2018. Nonetheless, this exhibition quite rightly induced sombre reflection. What a contrast there was between Orpen's slick portraits of the top brass, no doubt unfailingly pleasing to their subjects (particularly himself), and the wall of photographs showing the haunted faces of the ‘Poor Bloody Infantry’. Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861–1928), KT, GCB, GCVO, KCIE, Commander-in-Chief, France, from 15 December 1915 (1917, below left) and Self-portrait (1917, below, right).

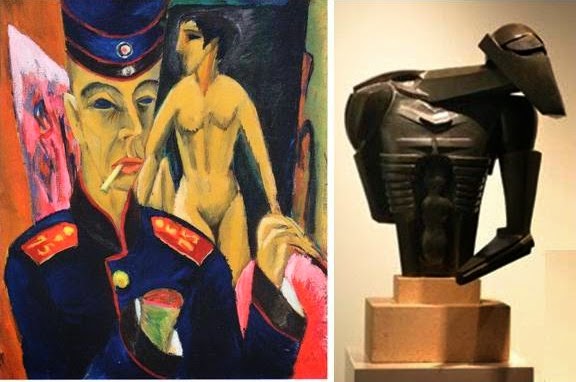

I saw for the first time some of Henry Tonks' famous pastel drawings of injured faces (they feature in Pat Barker’s Toby’s Room). The text didn’t point out that Tonks was originally trained as a surgeon. There was also an opportunity to see a work by the Die Brücke expressionist Ernst Ludwig Kirchner: Selbstbildnis als Soldat (Self-Portrait as a Soldier, 1915, below left) and Jacob Epstein’s Torso in Metal from The Rock Drill 1913 – 14 (below, right).

A bigger show with more German art would almost certainly have been of more value. Also, while screening German as well as British contemporary newsreel footage was highly desirable, it made the exhibition seem even more crowded. It might have been better left to the BBC, who will probably show most of what is worth seeing in the next four years.

No comments:

Post a Comment