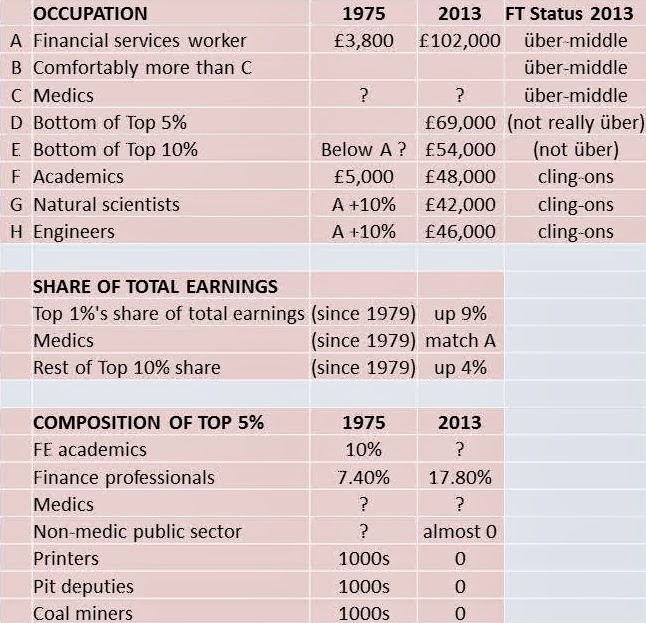

and the FT has returned to the subject, particularly the housing implications which I touched on in the last post. On 22 February (again a Saturday) the FT lead was High earners face London lockout, ‘Cling-ons’ priced out of homes by ‘uber-middle’, Camden and Hammersmith now unattainable. To help those who had missed the previous week’s story, it explained:

The purchasing power of a wealthy "über middle" is increasingly pushing the most desirable neighbourhoods out of the reach of "cling-ons" - the architects, engineers and academics whose salaries have failed to keep pace over the past 40 years. … People who could once have afforded Richmond, Wandsworth or Islington, are now buying homes in Barnet, Lambeth and Haringey, the data show.“the data” came from Savills estate agency, as in my post. They were also one of the sources for a map on page 2 of the FT titled “Britain’s middle class has been forced out of “prime” neighbourhoods” showing how for various districts the percentage of electoral wards where average housing costs for a household with a net income of £58,000 are unaffordable (ie need more than 35%):

The accompanying article focussed on Oxford, quoting Savills’ man on the spot:

A lot of the families who lived in north Oxford up until the time that I started (in 1961) were academic families. A lot of those have sold and gone out. And the people coming in might have an academic background, in so far as they were undergraduates here, but they have gone off and made their fortune either in industry or in the City or as senior consultants or accountants and so on.Another article described the difficulties faced by the cling-ons in affording private education, one of the attractions Oxford offers the übermenschen. An FT video is available, British middle class splits in two, featuring St Albans as the context.

The FT offered an interesting point about London from Chris Hamnett, professor of geography at King's College, London, who has charted its "gentrification" over 50 years. He said that the capital was now "a global centre for the international rich whose desire to secure a home in the capital amounted to "a process of global asset diversification". Next month Evan Davies has a two-part series on BBC2, Mind The Gap: London Vs The Rest, which hopefully won’t be just a eulogy of Bojoburg and will be prepared to look at the strains the capital is starting to impose on the rest of the country.

Some interesting issues may emerge from this fission of the middle class into über and cling-on.

Firstly, the political implications. If the Conservatives start to be perceived as the party for of the über-middle and above in London and the south east, can they ever win a national election? The foreign owners of London properties don't even vote. Worse, many of the under-60 middle class, whose support the Tories need, will be increasingly aware of their precarious cling-on situation and may find Labour's concern for the squeezed middle appealing.

Secondly, for how much longer will the NHS be able to pay its medical staff über-middle rates of pay?

Thirdly, are these stories underlain by an internal debate at the FT as to whether it should remain a national newspaper with declining print sales? Could it decide to push away the UK cling-ons? The FT could then concentrate its efforts on physical distribution only at the weekend and on-line subscription all week for the über middle and richer catchments, the dark bits in the map above and their equivalent across the Anglosphere? Much of the content of the FT’s How to Spend It supplements (see its “website of worldly pleasures”) concerns goods and services already clearly unaffordable by mere cling-ons. The weekend House and Home section is in a similar vein, Cheap as pommes frites*, being the headline of an article describing the cheapness of the French property market – from €4.5 million upwards.

*UK chips, US French fries.

Tyler Brülé is the editor-in-chief of Monocle magazine and he also writes a weekly column, The Fast Lane, for the Weekend Financial Times. On 1 March, a few days after this post appeared with its concluding bit of speculation, Brülé chose to write about a new Australian newspaper appearing for the first time that day, The Saturday Paper:

It comes at a time when many of the world's big news groups are considering what to do with their print editions from Monday to Friday (go exclusively on-line? Drop home delivery? Limit distribution to big cities only?) while placing more emphasis on their weekend editions (The FT, for example, has a big global campaign to bolster its weekend offering).

The Saturday Paper cuts out the cost that comes with running a newspaper throughout the week and is building on a readership base from an established sister magazine, The Monthly. Publisher Morry Schwartz's move to shake up weekend reading should be monitored closely by press barons, both established and emerging.The FT on 1 March seemed to be giving the über-middle/cling-on thing a bit of a rest.