Note: this post is based on a visit to the Fondation in early May 2105

The Fondation Louis Vuitton in Paris was opened in October 2014 by Francois Hollande, President of France, and Bernard Arnault, President of LVMH - Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton - and one of the wealthiest people in France. In 2001 he visited the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao and met its architect, Frank Gehry. Five years later the Fondation was established as a private cultural initiative by LVMH to support contemporary artistic creation. Under a 55 year lease from the City of Paris, the Fondation’s building, designed by Gehry, is set in one hectare of land in the Bois de Boulogne next to the Jardin d’Acclimatation.

Like Gaul, a visit to the Fondation can be divided into three parts: the current exhibition, the display from the permanent collection and the building itself.

Keys to a Passion

In May 2015 the current exhibition is Les Clefs d’une passion (Keys to a Passion), “a selection of major works from the first half of the 20th century that established the foundations of modernity”. It is organised into four sequences: Subjective Expressionism, Contemplative, Popist (popiste) and Music which are in accord with the themes which structure the Fondation’s own collection (… en resonance avec les quatre axes structurant, de façon plastique et mouvante, la collection …).

Subjective Expressionism “evokes the questions each of us have about life, death, anguish, solitude and the desparate rage to live, despite oneself, despite others …”. It also provides a chance to see Munch’s The Scream (1893? 1910?, below left), a work normally confined to the Munch Museum in Oslo and not made available for the 2012 Pompidou Centre/Tate Modern Munch exhibition. That show was, of course, intended to have a post-1900 emphasis but so has Keys to a Passion!

A series of self-portraits (1934, above right) by Helene Schjerfbeck (1862-1946), a painter known best in her native Sweden, stand up to their proximity to The Scream. As well as a sculpture and two oils by Giacometti, this section includes two major 1949 works by Francis Bacon, Study from the Human Body (below left) and Study for Portrait (below right):

a Malevich not at Tate Modern in 2014, Complex Presentiment or Bust with a Yellow Shirt (c 1932, below left), and Otto Dix’s Portrait of the Dancer Anita Berber (1925, below right):

Contemplative occupies three rooms, the first dominated by two of Monet’s Water Lilies of 1916-19 borrowed from Paris museums. On one side of the room are four lake and mountain landscapes by the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler, on the other there are four studies of Lake Keitele from 1904-05 by the Finnish painter Aksell Gallen-Kalleila, one from the National Gallery in London. Complementing these are five seascapes, two by Emil Nolde and three from 1909 by Mondrian, the style of these being in marked contrast to some of his later works in the next room, for example Composition in line, second state (1916-17, below left) and Lozenge Composition with Yellow Lines (1933, below right):

However, this room is dominated by three of Malevich’s most significant works (again not at Tate Modern) lent from St Petersburg: Black Square, Black Cross and Black Circle, all c1923 and pointless to reproduce individually. They can be seen in the photograph (below top) with two of the Mondrians (including the one above left) and Brancusi’s Endless Column Version 1 from 1918. Opposite the Malevich’s, and to me as inducing of contemplation as the Monets, is a Rothko, No 46 (Black, Ochre, Red over Red) (1957, below lower):

In the next room an interesting Bonnard (Summer, 1917) is, to put it kindly, at a disadvantage near to a Picasso plaster sculpture (Head of a Woman with Large Eyes, 1931) and three of his Marie-Thérèse Walter paintings. One of these (Nude Woman in a Red Armchair, 1932) is familiar in London from Tate Modern, as Woman with Yellow Hair (1931, below left) and Reading (1932, below right), no doubt are in New York (Guggenheim) and Paris (Musée Picasso) respectively:

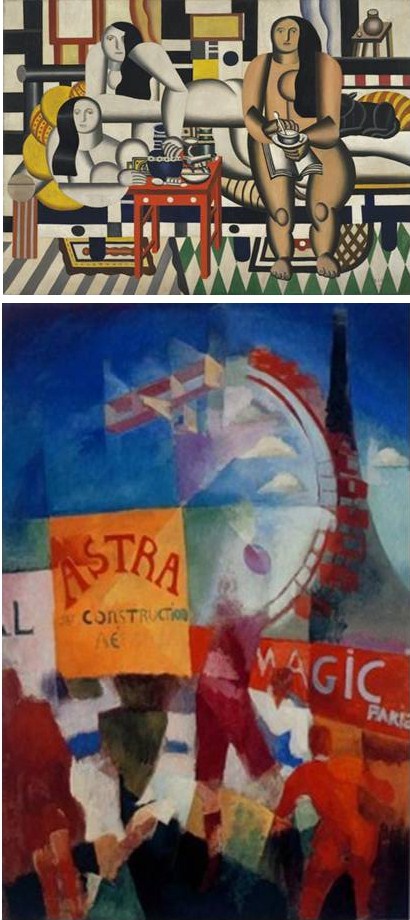

I found Popist the least successful of the four sequences. Picabia arguably anticipated Pop art and deserves a place in a section “resolutely engaged with the vitality, momentum and progress of modern life” but five large pictures, three of them nudes “veer[ing] between a joyous exaltation in nudity and a vaguely salacious eroticism”? Again three Legers, Three Women, (1921-22, below top), but the one other painting in the sequence, Robert Delaunay’s The Cardiff Team (1912-13, below lower) was new to me:

Music provides a triumphant conclusion to the exhibition, the four Kandinsky panels and works by Kupka and Severini being swept aside by two Matisse masterworks, The Dance (1909-10, below top) from St Petersburg and The Sorrow of the Kings (1952, below lower) from the Pompidou Centre in Paris (not lent to the Tate Modern/MoMA show last year):

Keys to a Passion certainly achieves its goal in bringing together some of the major art works of the 20th century. These include items which rarely travel, and for that as well as other reasons is worth making an effort to see before it ends on 6 July.

Items from the Permanent Collection

Walking through these I was struck by Rachel Harrison’s Zombie Rothko (2011, below left) and Maurizio Cattalan’s Charlie don’t surf (1977 below right – the attendant and photographers are not part of the work). Harrison was awarded the Calder Prize in 2011 for exemplary work in the spirit of Alexander Calder.

It was pleasing to see works by UK artists including Ed Atkins’ video installations Us Dead Talk Love (2012) and Even Pricks (2013) and Tacita Dean, including her Lightning Series (2007) and Hünengrab (2008, below top). According to the caption it is one of a series depicting megalithic prehistoric stone formations in Cornwall (SW England). The series was inspired by Caspar David Friedrich’s Walk at Dusk (c1830-35, below lower), hence the title (Giant’s Tomb).

A large space is given to Sigmar Polke Cloud Paintings (1992-2009, below) – four paintings and a 4-billion-year-old meteorite, the third biggest discovered after a Siberian meteor shower in February 1947:

A small gallery is showing several works by Ellsworth Kelly, who was commissioned to provide works for the Auditorium (see below). These include Green Relief (2009, below left), Blue Diagonal (2008, below centre) and Purple Curve in Relief (2009, below right, lent by the artist):

There are also some fine Giacometti sculptures including Buste d’Homme assis (Lotar III), (1965, below left) and Grande femme II (1959-60, below right):

THE GEHRY BUILDING

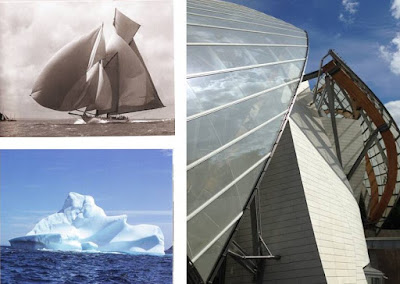

The interior of the Fondation building, containing the 11 gallery spaces (the underground ones vastly better than their equivalents at the National Gallery Sainsbury Wing in London), the Auditorium, shop and so on, is restrained and functional in contrast to the exterior. Some of the inspiration for Gehry’s design seems to have come from a yacht, the Susanne, built in 1911 and an iceberg (above), as well as from some of Paris’s famous metal and glass structures like the Grand Palais. The building is covered with over 19000 panels of white Ductal ® high performance cement (beton) and moving around the building and on the terraces provides a series of contrasts between the “iceberg” and the glass and steel “sails”. Its advanced design, fabrication and construction are a credit to French engineering.

There are some remarkable views over Paris and the Jardin, for example towards La Defense (below top). One of the terraces is displaying a living sculpture made of found objects by Adrian Villar Rojas, Where the Slaves Live (2014, below lower):

Inside are the Ellsworth Kelly works commissioned in 2014 for the Auditorium including Spectrum VIII (below right) and Color Panels Yellow and Red (below left).

Is the Fondation Louis Vuitton worth a visit? Definitely, but it may be a while before there is another show quite like Keys to a Passion.

UPDATE 3 JULY

Hopefully anyone in the UK interested in Frank Gehry will have been able to see Alan Yentob’s documentary, Frank Gehry: The Architect Says "Why Can't I?", in the BBC1 imagine strand before it disappears into iPlayer limbo.

Among the many points of interest are firstly that Gehry, when designing the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao in the mid-1990s, made use of what was at the time advanced software from France’s Dassault Group, aerospace being one of its main activities. Secondly he lived in Paris with his young family and the Jardin d’Acclimatation has very personal memories for him.

No comments:

Post a Comment