I remember years ago reading a holiday brochure which was urging travellers to visit Arles in southern France, one of its attractions being a Van Gogh museum. Well certainly Arles was the setting for some of Vincent van Gogh’s most famous paintings, eg The Yellow House (1888 above), but there’s no Van Gogh museum there, nor is there ever likely to be, unless Amsterdam’s Museumplein, along with the rest of northern Europe, is threatened by an ice sheet. In the meantime, thanks to van Gogh’s descendants, the world’s largest collection of his works remains in the country of the painter’s birth at the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam, very near the Reijksmuseum. Anyone visiting the city should take the opportunity, if they can, to see the originals of some of the most famous images in art, like The Bedroom/Bedroom in Arles (1888, below – there are other versions in Paris and Chicago).

On the Museum’s ground floor there is an introduction to van Gogh (1853-90), mainly in the form of a series of self-portraits, concentrating on the ten years up to his death, the dominant period of his artistic life. (Below right: Self Portrait with Grey Felt Hat, 1887; below left: a portrait by his Australian friend, John Peter Russell, Vincent van Gogh, 1886) A display case shows a palette that van Gogh used and some of his tubes of paint. These had come into use in the 1840s, and were being filled with the new pigments developed by chemists in the 19th century (but see below). Renoir said that “Without tubes of paint, there would be no Cézanne, no Monet, no Pissarro, and no Impressionism” and, one can assume, no van Gogh.

On the first floor the visitor’s initial encounter is with work from van Gogh’s early years as an artist in Brussels and Holland, sombre landscapes and studies of peasant life. Probably the best-known is The Potato Eaters (1885 below):

But in March 1886 Vincent moved to live with his brother Theo in Paris. Tuition and encountering Impressionism had a transformative effect on his art. Among the artists he met was Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, whose Young woman at a table (Poudre de riz, 1887, below left) was owned by Theo and eventually passed to the Museum. Vincent painted his lover, a café owner, in a similar style – In the café Agostina Sagatori in Le Tambourin (1887, below right):

Van Gogh put on an exhibition of his Japanese woodcuts in Le Tambourin. These had become available in the 1870s and were admired by contemporary artists. Not only were some of his works - Bridge in the rain (1887, below left) directly after Hiroshige, but others like Fishing Boats on the Beach at Saintes-Maries (1888, below right) reveal the indirect influence of Japanese art.

In the spring of 1888, and sponsored by Theo, van Gogh left Paris for Arles where he would work frenetically, attempt to set up an artists’ colony in the Yellow House, and be joined later in the year by Gaugin. Works from this time are on the Museum’s second floor, for example, The Harvest (1888, below left) and Gaugin’s Chair (1888, below right):

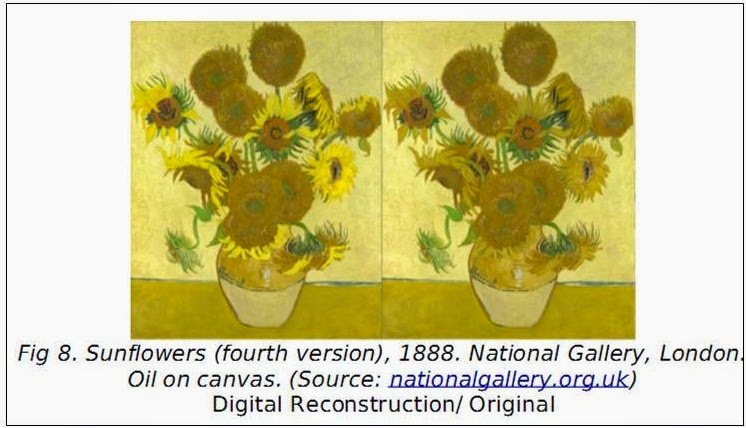

And one version of probably his most famous work, Sunflowers:

There are two series of van Gogh Sunflowers. The first is of four pictures all made in Paris, the second is of four painted in Arles in 1888 with three more “Repetitions” made in 1889. Last year the Van Gogh Museum’s Repetition was exhibited in London alongside the National Gallery’s 1888 version (below left). The NG’s Vincent’s Chair (1888, below right) is shown for comparison with Gaugin’s Chair and The Bedroom, both above.

|

| Both in the National Gallery, London |

The recently redeveloped third floor of the Museum covers the period 1889-90. By the end of 1888, Van Gogh’s health had deteriorated and he would spend much of 1889 in the asylum at Saint-Remy. In 1890 he left the south and took up residence in the village of Auvers-sur-Oise where he would produce two of his most famous paintings, both in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris: The Church at Auvers (1890) and a portrait of the local doctor who was supervising him, Portrait of Dr Gachet (1890, 2nd version):

|

| Both in the Musée d'Orsay, Paris |

At the end was a temporary loan from the UK Arts Council of a picture I’d last seen in 2013, Francis Bacon’s Study for Portrait of Van Gogh VI (1957, below right), alongside a reproduction of the van Gogh self-depiction, The Painter on the Road to Tarascon (1888, below left), destroyed, like one of the four 1888 Arlesian Sunflowers, by fire in WW2.

In September 2015 a new entrance to the Van Gogh Museum from the Museumplein, designed by Kisho Kurokawa & Associates, will open. The exhibition Munch:Van Gogh, exploring parallels between the two artists, will transfer from the Munch Museum in Oslo later that month.

UPDATE 14 MARCH

Since my post the March issue of Apollo, an international art magazine published in the UK, has appeared with the Van Gogh Museum as its cover story. The editorial by Thomas Marks is on the theme of the single-artist museum (he likes Leighton House) and he says that after visiting the Van Gogh Museum recently he “left with the glow of a pilgrim”. His accompanying article, Versions of Vincent, describes the Museum with a much more informed eye than mine and reports his interview with the Museum’s director, Axel Rüger.

In the last few days there has also been coverage in the mainstream media of the problem of deterioration of some of the pigments use by van Gogh (see above). The Mail Online Science and Tech provided more details than most and gave links to the recent Belgian chemical research.

No comments:

Post a Comment