I have posted here several times about NT Live screenings (most recently Les Liaisons Dangereuses) but not about the similar offerings this year from the Kenneth Branagh Theatre Company, in partnership with Picturehouse Entertainment. The Winter’s Tale and Romeo and Juliet from the Garrick theatre in London have now been followed by John Osborne’s The Entertainer, broadcast on 27 October.

The Entertainer was Osborne’s second success at the Royal Court Theatre following his Look Back in Anger in 1956. Laurence Olivier, under the influence of Arthur Miller, had asked Osborne for a part in his next play and in 1957 took on the role of Archie Rice, the music hall performer whose best days were behind him. Branagh, although not a protégé of Olivier, seems to have been drawn inexorably to follow his footsteps, starting at drama school when he wrote to Olivier for advice and was advised “to have a bash and hope for the best.” Later for example, in 1990 Branagh directed and took the lead role in a new filming of Henry V, in 2007 he directed an update of Sleuth and in 2011 he played Olivier himself in My Week with Marilyn (set in 1956 when Olivier filmed The Prince and the Showgirl at Pinewood with Monroe, then married to Arthur Miller). Unsurprisingly, in his company’s revival of The Entertainer Branagh has cast himself as Archie.

For a detailed synopsis of this play about the decline of the theatrical Rice family, see Wikipedia, although this production has been restructured into two acts. Was it worth reviving yet again? In many ways the play is dated and increasingly inaccessible – who under 75, or even 80, now remembers the world of music halls (the UK’s equivalent to vaudeville)? And the electrical counter of Woolworth’s is already almost as forgotten as Max Miller. But some of Osborne’s themes, like the grip of Britain’s class system, particularly its elite private schools, remain familiar, and it is still the same gloved hand which waves at us from a golden coach, poignantly described by Archie’s daughter. In an interview with Andrew Marr televised on 23 October, Branagh probably over emphasised the resonances in The Entertainer between post-Brexit Referendum Britain and the country 60 years ago in the humiliating aftermath of the Suez debacle, though he could have mentioned Archie’s dislike of his Polish neighbours. More fundamentally, Branagh was unconvincing as Archie. Energetic for sure, and a master of tap, song and dance, but the well set-up theatrical knight and actor-manager talking on The Marr Show failed to make the transition required to be totally believable as the seedy, end-of-the pier, end-of the-road “has been”, Archie Rice. The older parts are the best ones in The Entertainer: Gawn Grainger as Archie’s dad, Billy, and Greta Scacchi as Phoebe, Archie’s second wife, were first class. But Sophie McShera as Jean looked and sounded too juvenile for a character who turns out to be more worldly and committed as the play went on. The clever set morphed from stage to home to accommodate Osborne’s numerous scene changes with the minimum of interruption.

Three stray points. Firstly, did people really drink neat gin so copiously in the 1950s? Secondly, was Branagh deliberately bringing in what seemed to me like a hint of Tony Hancock’s delivery? Perhaps it was quite unconsciously done, but it’s worth noting that Hancock came from a stage family at the end of the music hall era. Finally, was I alone in finding some of Osborne’s dialogue uncannily like that of Harold Pinter, people speaking past rather than to each other? Pinter began to write for the theatre in 1957, The Birthday Party premiering in 1958.

Sitting in a cinema, this production was an unsatisfactory experience by comparison with the NT Live performances I’d seen previously. Those were free of transmission glitches of the type which interrupted the first Act of The Entertainer, albeit briefly. Much more trying was the projection which utilised “CinemaScope within a 16:9 frame” (as for the transmission of Romeo and Juliet, apparently). No doubt there were good technical reasons for this (the staging and cinema projection technology perhaps) but the resulting image quality at the left and right extremes of the frame was poor. This might not have mattered if the characters had remained together on the centre of the set but Archie seemed to like to address his family and the audience from stage right!

31 October 2016

28 October 2016

Mia Hansen-Løve’s ‘Things to Come’

I saw Mia Hansen-Løve’s L’Avenir in France during the summer and have now had the benefit of the subtitled UK release. Why the French title could not be translated literally as ‘The Future’, rather than reviving a celebrated usage by HG Wells in 1936, who knows?

Isabelle Huppert’s Nathalie Chazeaux is a Parisian philosophy teacher with grown-up children. After an ultimatum from their daughter, Nathalie’s husband Heinz (André Marcon), who also teaches philo, leaves her for his girlfriend, taking some of Nathalie’s books with him. Other traumas follow: Nathalie’s mother goes into a terminal decline; she has to take final leave of her husband’s family’s holiday home in Brittany; her publisher no longer thinks her books fit the market; going to the cinema solo she falls prey to a molester. Worse, philosophy being such an important part of Nathalie’s life, she finds herself at odds with Fabien (Roman Kolinka, right) a former pupil who seems to be turning towards anarchism. But after all this prospects of a happier future for Nathalie begin to emerge, not least as a grandmother. Huppert provides a totally convincing portrayal of a woman, and it could only be a woman, having to cope with so many intellectual and practical demands at the same time. Unsurprisingly unsentimental, Nathalie sends Heinz away rather than let him rejoin the family for poulet on Le Reveillon (chicken for Christmas Eve supper).

Philosophy is a prestigious subject in the French baccalauréat (approximately A-level in the UK or high school diploma level in the US) though Nathalie seems to be teaching at the even more demanding ‘prepa’ level which candidates for the grandes écoles have to achieve. For Arts students taking the bac literary stream, philosophy has the highest weighting (coeff) of all subjects. In France exams are marked out of 20, 16 (80%) is a very high mark. There is a “little primer” on the philosophical references in L’Avenir on the ScreenPrism website. Some reviewers have referred to the Cazeaux as “academics”, but, although their pupils will call them profs, they are not university teachers.

Mia Hansen-Løve’s The Father of My Children impressed me in 2009 with its maturity of insight and elegant filming. L’Avenir is of just as high a standard, shot in Brittany and the Vosges as well as Paris. The director/writer draws heavily on her own experiences and discussed the similarities between Nathalie and her own mother with Xan Brooks in the Guardian. Hansen-Løve made an interesting choice of music, perhaps the most significant piece is the Schubert lied, Auf dem Wasser zu singen (To sing on the water), D774, sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau:

…

Like yesterday and today may time again escape from me,

Until I on towering, radiant wings

Myself escape from changing time

Isabelle Huppert’s Nathalie Chazeaux is a Parisian philosophy teacher with grown-up children. After an ultimatum from their daughter, Nathalie’s husband Heinz (André Marcon), who also teaches philo, leaves her for his girlfriend, taking some of Nathalie’s books with him. Other traumas follow: Nathalie’s mother goes into a terminal decline; she has to take final leave of her husband’s family’s holiday home in Brittany; her publisher no longer thinks her books fit the market; going to the cinema solo she falls prey to a molester. Worse, philosophy being such an important part of Nathalie’s life, she finds herself at odds with Fabien (Roman Kolinka, right) a former pupil who seems to be turning towards anarchism. But after all this prospects of a happier future for Nathalie begin to emerge, not least as a grandmother. Huppert provides a totally convincing portrayal of a woman, and it could only be a woman, having to cope with so many intellectual and practical demands at the same time. Unsurprisingly unsentimental, Nathalie sends Heinz away rather than let him rejoin the family for poulet on Le Reveillon (chicken for Christmas Eve supper).

Philosophy is a prestigious subject in the French baccalauréat (approximately A-level in the UK or high school diploma level in the US) though Nathalie seems to be teaching at the even more demanding ‘prepa’ level which candidates for the grandes écoles have to achieve. For Arts students taking the bac literary stream, philosophy has the highest weighting (coeff) of all subjects. In France exams are marked out of 20, 16 (80%) is a very high mark. There is a “little primer” on the philosophical references in L’Avenir on the ScreenPrism website. Some reviewers have referred to the Cazeaux as “academics”, but, although their pupils will call them profs, they are not university teachers.

Mia Hansen-Løve’s The Father of My Children impressed me in 2009 with its maturity of insight and elegant filming. L’Avenir is of just as high a standard, shot in Brittany and the Vosges as well as Paris. The director/writer draws heavily on her own experiences and discussed the similarities between Nathalie and her own mother with Xan Brooks in the Guardian. Hansen-Løve made an interesting choice of music, perhaps the most significant piece is the Schubert lied, Auf dem Wasser zu singen (To sing on the water), D774, sung by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau:

…

Like yesterday and today may time again escape from me,

Until I on towering, radiant wings

Myself escape from changing time

17 October 2016

Louise Bourgeois in Bilbao and Bruton

In this blog there have been several encounters with Louise Bourgeois’ ‘spider’ sculptures (at the Royal Academy, at the Guggenheim Bilbao in 2015 and at Hauser & Wirth Somerset in 2014), but with only one exhibition of her work. That was Do Not Abandon Me, a show at the RWA Bristol in 2011 of Louise Bourgeois gouaches which had been adorned by Tracey Emin with small drawings and handwriting. Now two more extensive Bourgeois exhibitions have come along in just a few months.

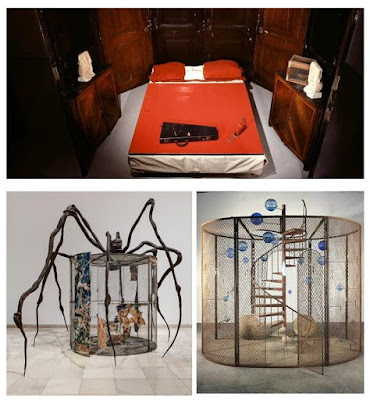

The first, again at the Guggenheim Bilbao, was Louise Bourgeois Structures of Existence: the Cells, which ran from 18 March to 4 September 2016. In 2015 this exhibition was at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and then the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow before Bilbao. From 13 October 2016 it will be at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark until 26 February 2017. The Haus der Kunst website and the Guggenheim’s continue to host extensive descriptions of the Cells and their place in the artist’s oeuvre. Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and died in her 98th year in Manhattan. She left France in 1938 on marrying an American art historian but continued to use French in titles of her works (eg Passage Dangereux, 1997, above) and when hand-writing on them. Between 1991 and the end of her life Bourgeois created 62 Cells, 25 of them in this show.

The Cells are room-sized spaces, often constructed as cages, which are stocked with objects having personal resonance for Bourgeois, often reaching back into her childhood (Red Room (Parents) 1994, below top). The full significance to the artist of a particular installation is unknowable but the visitor cannot fail to be drawn into her disturbing and claustrophobic world view (Spider 1997, lower left and Cell (Choisy) 1990-93, lower right).

At Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Louise Bourgeois Turning Inwards is an exhibition of sculpture and etchings. After opening with Spider 1996:

again these explore Bourgeois’ memories and feelings (I Go to Pieces: My Inner Life (#6) 2010, below top), but also reveal her keen observation of the natural world and the forms it provides (Swelling 2007, below lower).

There is also an exhibition of photographs of Louise Bourgeois taken in the final years of her life by Alex Van Gelder, Mumbling Beauty, and an opportunity to see the documentary Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine, directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach in 2008.

Louise Bourgeois Turning Inwards ends on 1 January 2017.

An Addendum about Artist Rooms: Louise Bourgeois at Tate Modern hopefully will be added to this post before too long.

The first, again at the Guggenheim Bilbao, was Louise Bourgeois Structures of Existence: the Cells, which ran from 18 March to 4 September 2016. In 2015 this exhibition was at the Haus der Kunst in Munich, and then the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow before Bilbao. From 13 October 2016 it will be at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark until 26 February 2017. The Haus der Kunst website and the Guggenheim’s continue to host extensive descriptions of the Cells and their place in the artist’s oeuvre. Louise Bourgeois was born in Paris in 1911 and died in her 98th year in Manhattan. She left France in 1938 on marrying an American art historian but continued to use French in titles of her works (eg Passage Dangereux, 1997, above) and when hand-writing on them. Between 1991 and the end of her life Bourgeois created 62 Cells, 25 of them in this show.

The Cells are room-sized spaces, often constructed as cages, which are stocked with objects having personal resonance for Bourgeois, often reaching back into her childhood (Red Room (Parents) 1994, below top). The full significance to the artist of a particular installation is unknowable but the visitor cannot fail to be drawn into her disturbing and claustrophobic world view (Spider 1997, lower left and Cell (Choisy) 1990-93, lower right).

At Hauser & Wirth Somerset, Louise Bourgeois Turning Inwards is an exhibition of sculpture and etchings. After opening with Spider 1996:

again these explore Bourgeois’ memories and feelings (I Go to Pieces: My Inner Life (#6) 2010, below top), but also reveal her keen observation of the natural world and the forms it provides (Swelling 2007, below lower).

There is also an exhibition of photographs of Louise Bourgeois taken in the final years of her life by Alex Van Gelder, Mumbling Beauty, and an opportunity to see the documentary Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, the Mistress and the Tangerine, directed by Marion Cajori and Amei Wallach in 2008.

Louise Bourgeois Turning Inwards ends on 1 January 2017.

An Addendum about Artist Rooms: Louise Bourgeois at Tate Modern hopefully will be added to this post before too long.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)